When Judy Bentley was in her first year of high school, she started feeling lost. Not just in the existential or emotional sense shared by generations of high-school freshman, but literally lost — she simply forgot how to navigate her high school. Bentley didn’t know it then, but she was showing the first signs of developmental topographical disorientation, a relatively rare and newly discovered neurological disorder that messes with the internal maps humans use to navigate, even in familiar surroundings. It’s like they’ve been equipped with a faulty GPS, one that tends to go offline at random times.

Bentley is now 47, and only discovered in March that there was a name for this strange and unsettling feeling, and that there were others like her. Giuseppe Iaria, the University of Calgary psychologist who first identified DTD in 2009, diagnosed her, and said in an email to me that he estimates about 1 to 2 percent of the general population has some degree of DTD. There’s no treatment, but Bentley and others have learned how to cope. She recently told Science of Us about her experience with the disorder.

Can you tell me about the earliest time you remember feeling that sense of disorientation?

It started when I was in my first year of high school, when I was 13. I mean, it’s already a hard time for adolescents, to try to kind of find their way in the world. But I was sitting in my math class, and there was nothing unusual going on; it’s not like something triggered this. And then, suddenly, my memory of my physical surroundings vanished. It was just gone.

What does that mean, exactly? What did that feel like?

I had no idea how the school was laid out. I didn’t know what was beyond the classroom door. I didn’t know where my locker was. I didn’t know how to leave the building. I didn’t even know how to get back home — and one of your first instincts, when you’re scared, is you want to go home, right?

But all those memories were wiped out. I mean, I knew I was in math class. I knew I was sitting beside my best friend. I knew what was going on, but it was like — my maps were just gone. They were gone. I had no idea how to navigate anywhere. So that first initial one lasted an hour. But then, not too long after that, it became a daily experience.

So what did you do that day, for that hour while it was happening?

Well, I of course had to switch classes when the bell rang, so I spotted a student who was in my next class, and I followed her.

Smart.

But once I got there, I had no idea which desk was mine. So I waited for everyone to sit down, and then I grabbed an open desk because, you know, you don’t want to sit in someone else’s place. So that’s how it first started.

And then it branched off. So what happens with me is I have four different maps that I cycle or flip through throughout the day. It’s kind of hard to describe. But each map contains accurate information; it’s just that each one appears and feels different.

Can you try to describe the differences between those four maps?

They’re all the same information, but I have the sensation of it being new, of it being unfamiliar. So, I’ll just kind of give you an example here. If you walk into a new environment — you know, if you walk into an office — you learn the layout. And so you know where your desk is, where the restrooms are, you know where the break room is, all that kind of stuff. But then that map, for me, will disappear, and everything gets wiped out. And I will have to relearn the layout. And then, again, the map will flip, and I’ll have to learn the layout again. So because I have four different mental maps, I have to learn everything four times, in terms of spatial things and navigating.

On average, a new map will appear every 20 minutes. But I have had instances where I’ve lasted a few hours in one map, which is wonderful. But it can also flip as soon as every few minutes, too. But on average, it’s about every 20 minutes.

It’s different for other people with DTD. A lot of them have the sensation that they’re turned around — so they may be driving west, but they feel like they’re driving east. Or, a lot of them experience either a 90-degree or a 180-degree shift in their spatial awareness. But the effect for them is the same as it is for me — it’s a feeling of disorientation. It’s a feeling of being lost in an unfamiliar landscape.

And, just to be really clear — it doesn’t matter how familiar you are with an environment, right? It can happen anywhere?

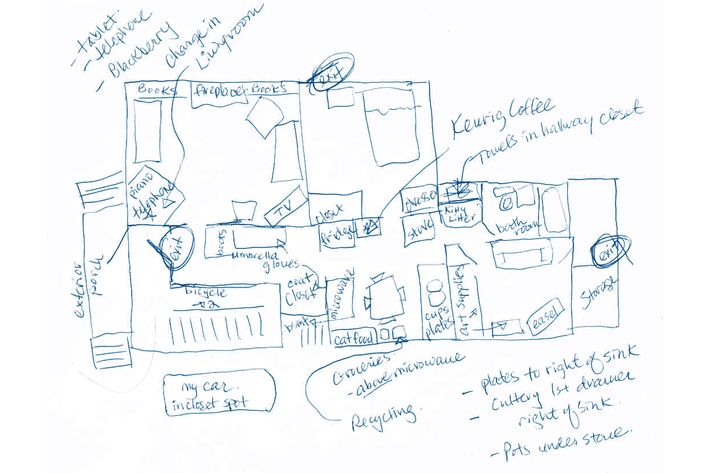

That’s right. Like, I’m in my own home, and I can’t find anything! It’s very frustrating. Not just losing my way navigationally — I can never find my Blackberry, my phone, it’s just basically everything. Because I put something down in one map, then my map flips, and I don’t have that recall of where I’ve put it. I think I spend about a third to a quarter of every hour just wandering around looking for stuff. It’s not terribly productive.

And I do sometimes mix up places in my home, too, like I’ll think the stove is where the fridge should be. Though I’ve never gone so far as to try to cook a meal in my fridge! But things just seem out of place. They seem turned around. It’s frustrating. It’s very frustrating.

How else does DTD impact your everyday life?

For one thing, I can’t rely on familiarity at all. Which is kind of discomforting. It’s also hard for me to remember things clearly. If I learn something in one map, and then I flip to another map, it’s difficult to retrieve that information. It feels like I learn it in the first person, but then, when I flip to another map, it seems like secondhand information.

You mean, not just geographical information — things like facts and figures, too?

Yeah. Just anything in general that I’m trying to remember.

So this happened that first time when you were 13, and it lasted an hour, and then you were back to normal. But when did it start happening more frequently, like it does today?

It happened pretty quickly after that, the flipping between the four maps. It started happening more frequently, until the point where I didn’t have a feeling of home base anymore. And by that I mean, I didn’t have a base map that I was operating off of. I was just constantly flipping, flipping maps.

So you must have had to invent ways to cope with that near-constant flipping.

Yeah, at school, I began making little maps in the back of my binders. I drew a map of the school, of each floor of the school, and I had a map of each classroom, which showed me which desk I sat in. And I had maps pointing me back home as well. So that was one of the first ways I figured out how to cope with it. And I still do that today — I have a map of the local hospital, and one of my home, though I don’t use that one so much.

But back then, at school — you know, kids are kids. And one day, one of them grabbed my binder and he saw my little maps, and he sort of shouted to the class, Judy’s retarded! You know, kids are mean.

Yeah, no kidding.

So after that, I learned how to draw maps that didn’t look like maps. I used different little figures and symbols and scribbles, so that if my maps were discovered again, they wouldn’t know what they were. I would sometimes use circles, a spiral for the stairs, little X’s and lines and curves that I understood as maps but wouldn’t be recognized as such. I mean, when you’re a teenager, you’re trying desperately to fit in, and you’re tryimg to find yourself. You don’t want to be singled out at all. And DTD is a very isolating thing.

You were a very young teenager when you first started experiencing this. What did you think was happening to you?

I thought I was losing my mind. I mean, what I did is, I internalized it. I had the impression that it was different, it was abnormal. I thought I was crazy. And so I internalized it all, because I didn’t want to be found out. I felt very isolated. You know, it’s hard enough being a teenager without losing yourself every 20 minutes.

I also, that summer, became agoraphobic — you know, that’s the fear of open spaces, or leaving the house. I didn’t want to leave the house. I just felt safer at home.

So at this point, had you told your parents, or sought any help about this?

I told my mother initially when it happened, but she appeared upset by it. We just didn’t know what it was. And so I decided, at that point, not to talk to anyone about it. I was ashamed and embarrassed. I really thought I was losing my mind or something.

Have there ever been times where you got into a dangerous situation because of the DTD?

Really, the only danger is internal. I was lucky, it’s never landed me in a dangerous situation physically. But it certainly did psychologically. It’s often been embarrassing — I’ve had a lot of moments where I just don’t know where to go, or where to sit. In my career, I’ve done a bit of public speaking, so I’ve been up on the stage delivering a presentation. And then when I get off the stage, and my presentation is done, I don’t know where my seat is in the audience. So I just walk out into the lobby, and pretend I need a drink of water or something, until my maps flip back, and I can remember where I was sitting.

So in high school, you figured out how to cope with this by drawing yourself maps, and you said you sometimes still do that now. How else have you figured out how to cope?

Well, actually, I’m out of work because of DTD. I’ve been off since the spring of 2013. But what I had to do while I was working was just make lists, just write everything down, because I knew in another 20 minutes that those thoughts would be forgotten. So I made tons of lists, to-do lists. And I also had reminders on my computer that would pop up and ding and tell me to do things. Memory is such a big part of this — it’s so disruptive in that respect, as well as the navigational aspect. It’s very fragmented. It’s a very fragmented life, because every 20 minutes, you’re flipping to a — almost a different channel.

I’ve had to turn down a lot of opportunities that would’ve helped me, career-wise and financially.

What is your career?

I was an administrator at a non-profit. So a big part of my job was logistics. And that was very difficult. I was trying to be so organized, with a brain that chooses to disorganize itself. I ended up having to leave work because I just could not do it any more. I would have panic attacks every morning before I left for work.

But one of the challenges with a neurological or cognitive disorder is that people can’t see it. They see an articulate, well-groomed person, and they think, What’s the problem? I’ve encountered a lot of bias in that regard. I’ve spent so much time figuring out how to mask my DTD, so people that I worked with for years had no idea what was going on inside, the mental effort it took just to get through the day. So when I did leave work, I had a few dismayed people saying, What’s wrong with you? You look fine. So that’s the problem with these disorders, you can’t see them from the outside, so you do face a bit of bias.

And, I mean, this is a new disorder. It’s only recently been recognized.

Right. So can you talk about what it was like when you finally found out what this was, that it has a name, and that there are others out there like you?

Oh God, it was one of the best days of my life. At that point, I’d been through seven neurologists, psychiatrists, psychologists — nobody knew what it was. I was just basically treated as if it were a psychological disorder — one of my first psychiatrists thought I was delusional.

But so earlier this year, my neuropsychologist, she mentioned this research company called NeuroLab, and she said they were doing research on human navigation and that I should get ahold of them. So I did. I looked online, and — oh my God, I burst into tears. It was the first time I knew there were other people out there who have this. And so I talked to Dr. Giuseppe Iaria, he’s the fellow who sort of leads this whole team. I spoke with him at great length on the phone, and I did some online testing, and he diagnosed me with DTD.

So that was in March of this past year. Thirty-four years of searching, and I finally found an answer. I was ecstatic. And along with this answer, there’s a forum for people with DTD, and so we can write in, we can support each other. That was a real lifesaver for me.

How so?

Well, we’re sharing our challenges. Like, we walk in the kitchen, and we don’t know what’s behind the cupboard door. So just sharing the day-to-day challenges with someone else is such a relief. It’s so comforting to know that this is real, and that other people suffer from it. And there’s lots of them!

Now that I know what this is, it’s almost kind of fun to be part of this discovery. More and more people are just coming out of the woodwork now as they hear about Dr. Iaria’s work. I bet there are thousands of people walking around out there that could not find their way out of a paper bag. They’re embarrassed, you know, and they don’t know what it is. It can be very socially isolating. It was such a godsend to speak to Giuseppe, and to finally know what’s going on.

This interview has been edited and condensed.