Kids of a certain age lie rather frequently. This is both common-sense child-rearing wisdom and a fact that has been observed in experimental settings over and over. So how should parents deal with this fact? And how can they induce their kids both to act more honestly and to admit to dishonest behavior when it does occur? A new study in the Journal of Experimental Child Psychology offers some useful advice to parents: If you want your kids to tell the truth, don’t threaten them with punishment for lying.

For the study, a research team led by Victoria Talwar of McGill University had 372 kids between 4 and 8 years of age participate in a game in which a researcher had an unseen toy make a noise, and the kid had to guess what the noise was. After doing this twice, the researcher told the child that she had to briefly leave the room, and to not peek at the next toy while she was gone. She left for a time, during which a hidden camera (there’s always a hidden camera in experiments like this) captured whatever the kid did — or didn’t — do.

As it turned out, 67.5 percent of the kids peeked during the minute in which the researcher was gone, and the older they were, the less likely they were to peek (but the more likely they were to lie about having peeked). But more important is what happened when the researcher returned to the room: Depending on which experimental condition the kid was in, she made one of six statements to the kid. It’s easiest here to just quote directly from the study:

No Punishment–No Appeal condition

‘‘If you peeked at the toy, it does not matter. No matter what happened, I would not be cross with you.’’No Punishment–External Appeal condition

‘‘If you peeked at the toy, it does not matter. No matter what happened, I would not be cross with you.’’

‘‘If you tell the truth, I will be really pleased with you. I will feel happy if you tell the truth.’’No Punishment–Internal Appeal condition

‘‘If you peeked at the toy, it does not matter. No matter what happened, I would not be cross with you.’’

‘‘It is really important to tell the truth because telling the truth is the right thing to do when someone has done something wrong. It is really important to tell the truth.’’Punishment–No Appeal condition

‘‘If you peeked at the toy, you will be in trouble.’’Punishment–External Appeal condition

‘‘If you peeked at the toy, you will be in trouble.’’

‘‘Although I will be cross about peeking, if you tell the truth, I will be really pleased with you. I will feel happy if you tell the truth.’’Punishment–Internal Appeal condition

‘‘If you peeked at the toy, you will be in trouble.’’

‘‘Although I will be cross about peeking, it is really important to tell the truth because telling the truth is the right thing to do when someone has done something wrong. It is really important to tell the truth.’’

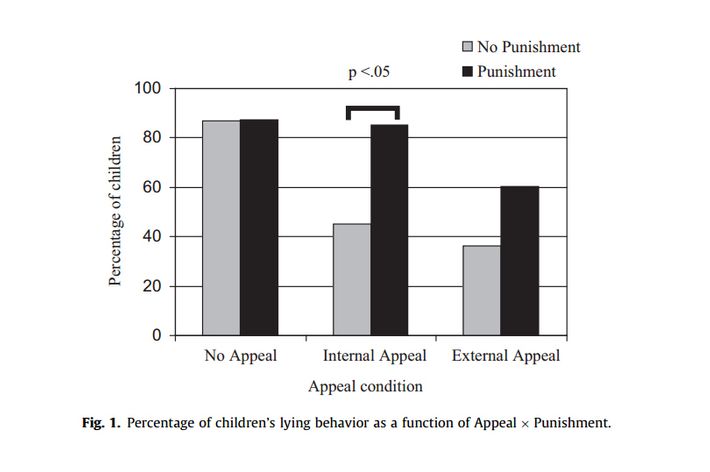

So basically, each kid was either threatened with punishment or not threatened with punishment, and given one of two reasons to tell the truth, or given no reason at all. Here’s how the different messages affected rates of truth-telling — this is the percentage of kids who lied, so the higher the bar, the more dishonest the kids were:

What’s the main takeaway here for parents? First, that kids — or kids in this study, at least — do seem to react when given a reason to tell the truth. And second, threatening to punish them appears to have the opposite of its intended effect, because you’re effectively telling a child to admit to something that will lead to them being punished.