This week, the Cut is talking advice — the good, the bad, the weird, and the pieces of it you really wish you’d taken.

“So, basically,” I said, “I don’t know if I should quit my job and freelance, or stay there for another year. What do you think?” I was in the dressing room of multiple Tony Award–winning actress Cherry Jones. I didn’t actually know Jones, and she didn’t really know me. But she had responded to a fan letter I’d written to her nearly two decades prior asking for advice about how to get along with my high-school drama teacher. (“I’ve had a tough time with directors,” she’d told me then, “and the best advice is to find a peer who can make it fun and help you focus.”) Now, at 28, I was hoping she would tell me what to do again.

“I don’t know!” she responded now. “You know I’m not a Ouija board, right?”

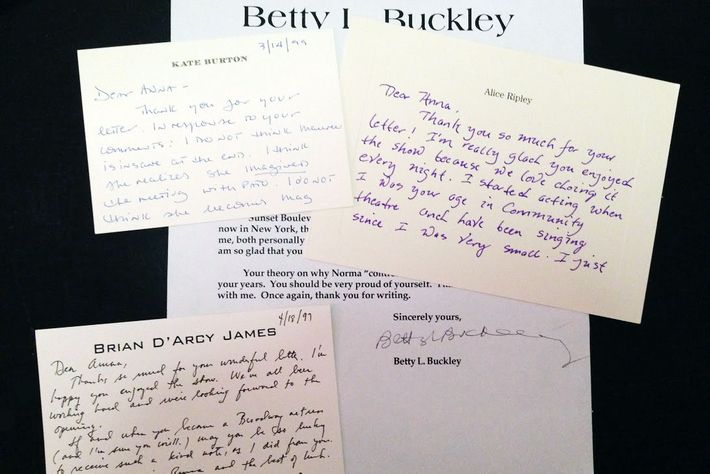

“Of course,” I said. I didn’t mention that throughout my adolescence, I did consider her — and, to a lesser extent, dozens of other Broadway actors and actresses — to be exactly that. From ages 10 to 16, I would write letters to the cast members (and not just the stars) of every Broadway show I saw, asking them how they did it and what advice they had for me. More often than not, they wrote back. Over six years, I amassed more than 100 handwritten letters — often with home addresses hastily scrawled in the upper left-hand corner — telling me some variation of “you can do it.”

As I got older and more savvy, I’d go beyond the “How did you become an actor?” question and tell them the specific problems I was facing as a theater-obsessed, braces-clad, mid-’90s tween: My mom wouldn’t let me take tap and jazz classes in the sixth grade. I couldn’t stand my eighth-grade chorus teacher. I felt ostracized by the upperclassmen when I was a freshman in the high school play.

I would read each response over and over, memorizing them like a script, sure that somehow, together, they represented a step-by-step plan for how to achieve my dream career. The advice varied from the affirmational (“Anything is possible, if you wish it to be.” — Idina Menzel) to the practical (“It’s not an easy life and you are often poor, so I strongly recommend having a way to earn a living as you go, like typing and shorthand.” — Sloane Shelton) to the depressing (“I’ve been pretty depressed since the reviews aren’t so good, so I’ve been roller-blading outside a lot.” —Melissa Errico, prompting me to rush out and buy roller blades).

Each letter was a page added to my personal How to Succeed in Show Business bible. I may not have been the most talented of aspiring actresses, but at least I could collect the most intel. These revelations—as well as the backstage visits — made my heroes seem like actual people. I saw that one actress, now a star on a Shonda Rimes drama, wrote a daily letter to God that she taped on her dressing room mirror. An Emmy-winning actress told me that she’d been worried throngs of people would be waiting for her at the stage door — until she saw something much worse: Only four or five were milling around the security gates she’d requested.

Seeing their private rituals, habits, and neuroses made understand that the adults I admired were just as confused and searching as I was. Which was comforting somehow.

Some actors I wrote to multiple times, but no one was more transformative for me than Cherry Jones.

I first wrote to her when I was twelve, after seeing the 1995 production of The Heiress. Her performance was simultaneously understated and commanding. For the first time, I understood what acting really was. I was gushing and awestruck in my letter, and instead of a pat good luck card, she wrote a two-page letter, telling me she was so pleased that the show was “worthy of such an exalted spot in your memory and heart.” I loved that she used grown-up vocabulary words, unlike other performers whose notes, though friendly, could be condescending. (“The way you get on Broadway is by working very hard and also by auditioning, which is trying out to see if the people in charge like you,” one well-meaning actor had written back.) I hadn’t been able to take my eyes off Cherry Jones during the performance; now in her letter I felt like she saw me.

So I kept writing to her, about disappointments and triumphs in the high-school theater department, questions about college, and the desire I had to be an actress — even though, with each passing year, it became clearer that my okay-for-high-school talent level wouldn’t ever lead to a professional career. She didn’t always write back, but even chronicling for her what was going on in my life made her a touchstone throughout my tumultuous teens and 20s. I loved that she was there; an adult who, without being invested in my life, seemed to care about what I was doing — and wasn’t afraid to open up about her own experiences.

“This character has much more spiritual maturity than I do,” she told me of her 1995 performance as Hannah Jelkes in Night of the Iguana, a role for which she’d won raves, “so sometimes I get nervous because I feel like she’s beyond me.” When she was starring in the critically acclaimed revival of Moon for the Misbegotten in 2000, she wrote, “I had a really hard time with this one — just a mid-life confidence crash. But I’ll get through it by working hard, keeping the faith … and knowing there’s not much else I’m trained to do except perhaps bicycle messaging.”

When I moved to New York City for college in 2001, it was comforting to know that, in a city of millions, Cherry Jones knew who I was and had my back.

One drizzly summer night when I was 20, drunk and wobbly on four-inch heels, I heard someone call my name as my friend and I navigated our way down West Fourth Street.

“What are you doing?” It was Cherry Jones on her bike, leaving the New York Theater Workshop, where she had been starring in the 2003 adaptation of the Michael Cunningham novel Flesh and Blood.

“We’re going to a bar,” I slurred, gesturing down the street. “We like it because they don’t card.” She nodded; pausing for a moment. “Be careful,” she said. “And do you need an umbrella?”

I shook my head and we went our separate ways. The next morning, I kept replaying the interaction in my mind, hating the way she must have seen me: drunk, confused, young.

Another time, heading to a midtown office space to conduct a creative writing class I didn’t feel remotely qualified to teach at age 27, I ran into her leaving a rehearsal for the 2010 production of Mrs. Warren’s Profession. Her “Good luck!” gave me the confidence boost I needed.

I ran into her a third time a few months after my mother died of cancer. “How’s your mama?” she asked brightly, even though she’d only met my mom a few times. I told her the news, feeling a weird combination of grief and relief as she said how sorry she was to hear that. My mom and I would never see another show together; I wouldn’t be able to call and tell her about my spontaneous Cherry Jones sighting. But Jones was still here; a small constant in my life at a time when nothing felt like it would ever be the same.

To be clear: I was in no way Cherry Jones’s protégée. I only communicated with her a few times a year, and there were never formal catch-up dates. To see her, I would get tickets to see whatever show she happened to be in, have the stage manager send a note up to Cherry, and then have a brief conversation with her post-show. Still, 20 years is a long time to be in any sort of relationship, however casual. She’s seen me through college graduation, my mom’s death, my first book, and my first kid.

Now, as a writer of young adult novels, I occasionally get letters (or, rather, e-mails, blog comments, or tweets) from teens asking for advice. I feel an obligation to respond, even if I don’t feel I have particularly unique wisdom to impart — in fact, much of it is cribbed from what my Broadway pen pals told me years ago. What I learned from being on the other side of the fan letter is that the advice you give matters less than that you take the time to show that you heard the question. And what I learned from Cherry Jones is that I want to be as much like her as possible.