Over the weekend, I was at a music festival and I ran into a friend of mine — let’s call him Jack — who was happily wasted with two of his bros (as in, actual frat brothers from our shared alma mater). We went to get more drinks, and Jack, since he’s a fancy Californian now, ordered a white wine, while the rest of us manly men got beers. As we were walking back to the stage, the most touching episode occurred: One bro smiled at Jack, and, with zero hesitation, slapped his wine, spilling half of it. Jack went to take a sip, and the same bro smacked it out of his hand. Jack smiled back, rolled his eyes, and took a slug of his bro’s Bud Light. It was glorious. Or maybe more accurately, brorious.

It was also, as I discovered from reading the research on teasing, a way of “communicating friendship,” as Arizona State University anthropologist Daniel Hruschka describes in his book Friendship: Development, Ecology, and Evolution of a Relationship. It’s apparently pretty universal: Hruschka captures a scene of two Wandeki men meeting in the highlands of Papua New Guinea. As one Wandeki crests a hill, he calls to the other, saying he wants to eat his intestines. This is not a sign of anger, Hruschka explains: “In the presence of a Wandeki friend, the phrase means something quite the opposite — unbridled affection and happiness at seeing a companion after a long separation.” The two hug, and the visitor replies: “A! Ene den neie” (“Yes, I should like to eat your intestines too!”). Hruschka lists other friendship customs: For the Dogon ethnicity in Mali, if your close friend dies, you’re supposed to show up to the funeral in rags and insult their family. For Bozo, another ethnicity in West Africa, Hruschka writes that “friends demonstrate their love by making lewd comments about the genitals of one another’s parents.” It’s a fact of life: Sometimes friends are mean.

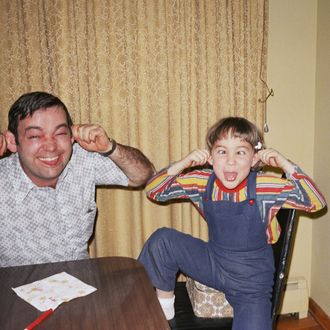

And this, if done right, is a good thing. As Olivia Goldhill writes on Quartz, psychologists have made a distinction between “antisocial” and “prosocial” teasing. As the names imply, antisocial teasing is cruel and akin to bullying. (It’s the kind of thing that will get an NFL lineman thrown off his team.) The prosocial teasing brings people, whether they’re kids or adults, together. Hruschka, the anthropologist, contends that friendship has three fundamental parts: “exclusive behavior,” or spending time with just one person or a group; “honest expressions of emotion,” or being transparently joyous, grief-ridden, or infuriated with someone; and “accepting vulnerability,” which not only includes Telling Them Things Nobody Else Knows, but also returning practical jokes and playful insults with an equal degree of glee. “This shows that one believes a friend’s intentions are good,” he writes, “and when teasing is reciprocal it communicates that each partner is certain about the other’s intentions.” Other research indicates that good-natured teasing is a way for romantic partners to express affection and for professional colleagues and athletic teammates to weave together social bonds.

The healthiness of teasing, if you want to call it that, has a lot to do with social dynamics: If one person has a higher social status than the other — the popular jock versus the ostracized nerd — then that’s going to be bullying. Also, one study on college students found that some topics are off-limits for good-natured teasing: Appearance, ethnicity, religion, and sexual orientation are all taboo. But it’s important, the researchers say, that kids learn how to get along with all the intestine-eating they’re going to face later in life.

Boston University psychologist Peter Gray tells Quartz that if parents and teachers try and shield their kids too much from any sort of smack talking, then they don’t learn to enjoy the crass banter that’s such a part of growing up or to stand up for themselves when it goes too far. Those sheltered kids have “heard from adults that [light-hearted teasing] is bullying and so they get really upset about it rather than knowing how to roll with the punches,” he says. It’s like the social equivalent of the microbiome: If your parents didn’t let any microbes into your house growing up, there’s a better chance you would develop asthma. And if they didn’t let you exchange barbs with your friends growing up, it might be harder to accept the vulnerability that’s a part of talking shit as an adult: When they slap away our drink, you guzzle theirs. When they eat your intestines, you eat theirs.