I hit a milestone today: It’s now been a full workweek since I last wore my Fitbit. And honestly, I am not doing great.

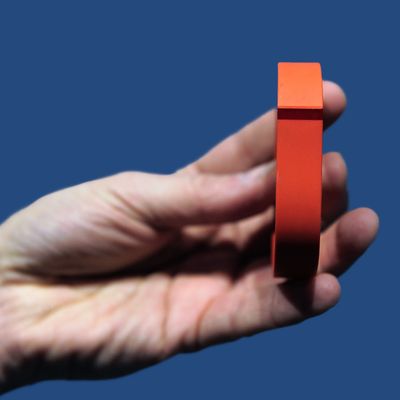

I took it off last weekend, the first time in months, for a combination of reasons both pressing and shallow. For one thing, it was becoming more stressful than motivating — there are only so many times you can pace around your apartment at 11:55 p.m. to cram in those extra steps before it starts to feel a little bit like an unhealthy fixation. Also, I really wanted to start wearing cute bracelets again, and the Fitbit takes up a lot of wrist real estate.

Earlier this year, Jordan Etkin, an assistant professor at Duke University’s Fuqua School of Business, published a study on the downside of activity tracking — namely, that it tends to suck the fun out of the activity, whatever that may be (she looked at walking, coloring, and reading): “Let’s say you like walking for fun,” she says. “It’s a relaxing, enjoyable activity, and you don’t really have any other reason to do it. You just like it. When you start to track behaviors like that, it basically provides an external incentive for engaging in those other fun activities. And so you start to think more about how much you’re doing, rather than just focusing on the enjoyment of the activity. It takes something that’s fun and makes it more like work.”

To be fair, the bracelet thing’s been a nice sartorial change of pace. But it’s also been overshadowed by a weird sense of nihilism that’s been dogging me the past five days — the feeling that walking doesn’t matter, that all my uncounted steps are somehow for naught. It’s not enough that they get me to where I’m going; they don’t have the meaning they used to. Which probably sounds crazy, if you’re not a Fitbit obsessive, and probably sounds right on par, if you are. Plenty of research has documented what happens when you start using Fitbit or otherwise tracking your behavior; less has looked into what happens when you stop. The research that is out there, though, feels at least a little bit validating: Transitioning from the quantified self back to the regular old self can be a long, grueling mental process.

But when you stop tracking, Etkin found, the sense of enjoyment doesn’t immediately come rebounding back — instead, you just lose that external incentive, too. “You’ve taken away the thing that is now driving your behavior, driving you to actually engage in this activity. As a result, because it no longer feels like fun, you do less of it,” she says. As part of her research, she looked at people who had started tracking themselves in certain activities and then stopped, comparing them to a control group of people who didn’t track themselves at all. Those who had quit tracking, she found, ended up doing less of their given activity than the people who’d never had any numbers attached to it in the first place.

So how long does it take to get back to fun? (Or, how long will walking extended distances of indeterminate step length bring on this sense of despair?) It depends. An activity like coloring, she says, can recover fairly quickly, because it’s rarely motivated by anything except the desire to have fun. But something like walking, because it’s already framed as a duty of sorts — as a healthy, responsible thing to do — will take more time to bounce back.

But it’s not just a question of making the slog back from extrinsic to intrinsic motivation. It’s also a question of dealing with loss, as dramatic as it sounds: Giving up Fitbit also means giving up a steady source of small pleasures that I’d come to look forward to each day. Fitbit is generous in doling out the rewards: a congratulatory buzz when you hit 10,000, a badge when you hit certain increments, a victory notification when you beat your friends’ weekly steps. They’re meaningless rewards, outside of the app — a badge doesn’t translate to anything IRL — but they’re rewards nonetheless, and they feel good, and now they’ve stopped.

Jeffrey Huber, a psychology professor at the University of Indiana who studies athletic performance, compares the Fitbit to behaviorist B.F. Skinner’s experiments on operant conditioning, or changing behavior through reinforcement. When a lab rat pulls the right lever, it gets a piece of food; when a human walks the right number of steps, it gets a little buzz on the wrist. “When you get feedback like that, it’s rewarding,” he says. “You get that excitement, you get a rush.” Once the animal learns what causes that rush, it’s going to want to do it again. Take away the source, and it’ll experience something like withdrawal.

But sometimes, when that reward feedback goes on too long, it can take an unpleasant turn. Last summer, marketing researchers Rikki Duus and Mike Cooray published a column in the Conversation detailing their research on what they called “the dark side of wearable fitness trackers.” Most of the stats they uncovered seem innocuous enough, even pretty healthy: Of the 200 female Fitbit users they surveyed, more than 90 percent made a concerted effort to exercise more each day to boost their step count. A little over half even reported they’d started walking faster since they got their Fitbits, an effort to reach their targets more quickly each day.

On their own, yes, these things are great. Exercise is great; choosing to get in shape is great. But more problematic, Duus and Cooray argued, was the way in which so many of their survey respondents related to their devices. Around 30 percent said they saw their Fitbit as an enemy, one whose primary purpose was to inspire guilt. Nearly 80 percent saw it as a source of pressure. More than half felt the Fitbit was actually the boss, controlling their daily routine rather than simply logging it.

And yet, 89 percent only took off their devices to charge them. And on the rare occasions that they went somewhere sans Fitbit, many reported feeling naked or incomplete. Behind these numbers, the researchers wrote, was the fact that the Fitbit wasn’t just something to wear or use — the study subjects had come to see it as a piece of themselves, something inseparable from their own identities.

In theory, this seems like a case for chucking the Fitbit once you reach that point; in practice, it means that giving it up is a lot more complicated than simply taking it off. “You no longer have to look to science fiction to find the cyborg,” they wrote. “We are all cyborgs now.” Which doesn’t sound so bad, when I’m having one of my moments of weakness. There have been a lot of those.