Burgundy lips, fuchsia lips, magenta lips, ChapSticked lips, orange-red, blue-red, red-red, ombré, matte, glossy, sparkly. In covering beauty at the fashion shows in New York, Milan, and Paris for over 25 years, I have seen a whole lot of lips (quick: what’s the difference between fuchsia and magenta?), plus a rainbow of eyes, and as many hairstyles as there are strands on the average model’s head. It’s a fertile time for beauty right now, with ideas zigzagging from the runways to Instagram to the streets to celebrities and back again, sometimes in a 24-hour period. But it wasn’t always that way.

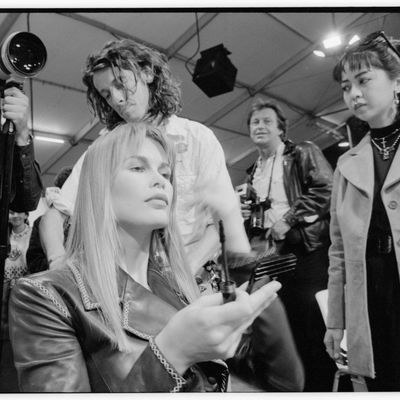

When I started interviewing the hair and makeup artists backstage at the shows, the only reporters in the room were from CNN and Fashion Television. “They’d bump into us and figured they might as well shove a microphone in our faces,” says makeup artist Dick Page. Beauty was clearly an afterthought. The designers’ objective was to present an atmosphere of chic in the Paris Lady mold: red lips, smoky eyes, and a chignon that didn’t steal attention from the clothes. Yves Saint Laurent, Hubert de Givenchy, Ungaro, and Valentino followed this aesthetic, season after season. Sometimes the models even did their own makeup.

I remember sitting at an Armani show in the early ’90s next to Polly Mellen, the mother of all fashion editors. We played “Name That Model,” trying to see if we could figure out who was hidden under the makeup and hair and hats. If you squinted, you could see Christy Turlington, Linda Evangelista, and Claudia Schiffer. Even supermodels were indistinct.

In the mid-’90s, a few designers realized that the makeup and hair could do more than just disappear in a blur of prettiness; they could express bigger ideas about female appearance. Sometimes the message was political and discomfiting, as it was at Jean Paul Gaultier’s controversial Hasidic show, where he put the models in wigs with sidelocks. Over the years, he included older models, big models, and men in drag, opening the audience’s eyes to other sorts of beauty. His shows had the atmosphere of a freewheeling, unpredictable party.

A big-deal change in beauty came in around 1994 when Helmut Lang stripped the models of makeup and hairstyles. I remember seeing Dick Page backstage rubbing Vaseline on the cheeks. Guido Palau, the hairstylist, tousled the models’ hair and tucked it behind their ears. Done! It was anti-artifice but it wasn’t anti-beauty. “The makeup and hair looked touchable,” says Page. “It wasn’t abstract. It was attainable. It had energy.” The models looked like real, live human beings. “It didn’t seem subversive until people told me it was,” says Page.

Designers discovered that beauty could startle the audience — offend them, surprise them, challenge or seduce them — and still sell the clothes. The creative dynamic between the designer and the beauty team became a wild adventure, crackling with life.

Some of the trends meandered off the runways to Hollywood and then to department stores and prom photo booths. Dick Page remembers buying black nail polish at a beauty-supply store, mixing it with a bottle of red and giving it to Sheryl Bailey, the manicurist for a Liza Bruce show. Chanel presented its own black-red on the runway and called it Vamp. Next stop was on Uma Thurman’s nails as she danced with John Travolta in Pulp Fiction. From there, the unlikely dried-blood nail color became a classic in a smooth path from the runway to Hollywood to the neighborhood salon.

This kind of marketer’s dream works better by accident than design. But M.A.C and NARS in particular have had success sponsoring fashion shows for decades. M.A.C started in 1994 and is the biggest beauty sponsor with 34 fashion weeks in 29 cities from Dubai to the Dominican Republic. It’s a multimillion-dollar operation for a brand that prides itself on its relationship with makeup artists and creativity. Sponsorship comes in different shapes and sizes, but generally M.A.C provides designers with makeup and makeup artists. In return, the company road-tests new products at the shows, learns about trends from the sources, disseminates those trends to the M.A.C counters around the world, and gets piles and piles of press. “Fashion is in our veins,” says John Demsey, executive group president at the Estée Lauder Companies. “Anybody can buy a show, sponsor a famous makeup artist, and get a cover credit. But nobody can do it for 20-plus years sustainably and authentically.”

The backstage rooms now are choked with beauty writers, bloggers, Instagram influencers, and video crews. They crowd around the hair and makeup artists with their iPhones outstretched, recording nuggets that may turn into the next big Chanel-Vamp-size trend. Maybe. “There’s nothing out there that’s new,” says François Nars, with a sigh, having seen everything since he started at 19 as an assistant at the Paris shows. The biggest trend in makeup now — contouring and highlighting — didn’t bubble up from the runways at all. “We have the Princesses Kardashian to thank for that flawless, high-glamour look,” says Page. There’s even a brand-new counter trend. “Someone asked me last week about non-contouring, which I didn’t even know was going on,” says Demsey. It’s Newton’s law applied to beauty: For every action there is an equal and opposite reaction. Hairstylist Guido Palau believes that the greatest beauty message today is not red or fuchsia or magenta lipstick or any neatly catalogued look. It’s the freedom to reject it all. “Women don’t have to do their hair today; they don’t have to have a blowout or present themselves in such a manicured way,” he says. “And that’s a trend from the runway. It’s a runway success.”