For many black women, a hair salon is a microcosm of the black experience: It’s a retreat, a familial epicenter, a mood-lifter, and yes, a place to go when you’d like to feel very pretty. I first recognized the strange comfort of a room dense with heat and the smell of hair during my childhood summers in southern Ohio. While I sat and thumbed through the latest issue of Highlights, the air would pulsate with the rhythm of my aunt and her hairdresser’s staccato laughs. I knew then what I know now: that the salon was good, and that I belonged.

But also, a hair salon is a throughway of trial-and-error, where the errors sometimes outweigh the triumphs; it’s a frustration stronghold, and a spotlight that beams down on your othered state. There was a time when an alluring Yelp rating drew me to a certain salon in D.C. On the few occasions I plopped into one of its chairs for a trim and a blowout, I felt alien in my surroundings. I never developed a decent rapport with my stylist, and for that I am wholly to blame. You see, my mind was preoccupied by the fact that I would be charged an additional $20 because I had “natural” hair. How unusual, I thought, to pay extra for something that grew out of my head with the same ease as the white women in the chairs next to me? I knew then what I know now: that the salon was bad, and that I was unwanted.

A hair salon is many things to different people. Men recognize its importance. My dad, for example, frequented the same barbershop every week for more than 30 years. Sometimes he’d return home with tokens of his weekly trip: a lousy bootleg of a blockbuster or a mysterious potion for soft curls. He continued to go even as his cuts grew a little more uneven and a little less pristine under his barber’s aging hands. He only switched barbers this May, when Eddie died.

For women, each part of the salon experience — the atmosphere, the cost, the stylist, the results — is a star revolving around her world. If one star collapses, everything is thrown off course. This is true for women of all races and classes, but especially so for black women.

When black women seek salon and hairstylist recommendations, they might ask other black women. Sometimes this is impossible. They might sift through Yelp reviews instead. Frequently this is a crap shoot. Jihan Thompson and Jennifer Lambert are attempting to manicure this prickly landscape with their new app, Swivel.

I was introduced to Swivel by — who else? — another black woman. She exalted the quality of stylists offered within the appointment-booking app, but I’d heard this tune before. There are dozens, if not hundreds, of beauty booking apps around today. Most aren’t very good. Some charge ridiculous prices or pair you with incapable stylists who awkwardly fumble with black hair. And, on a technical level, some of these booking apps don’t work at all (I’ve encountered glitchy software, and one time my appointment didn’t sync with the stylist’s app and I waited outside in the cold for an hour).

But Swivel is different. It says so on the company’s homepage: It’s a “better beauty experience for women of color.” Through a series of questions, the app connects users with a curated pack of stylists and salons in New York — though when I met with Thompson earlier this month, she explained Swivel plans to service more cities in the future.

Here’s how it works. Once users download the app, they answer a few simple questions: Do you want a haircut, cornrows, or a blowout? There are 23 general-service options from which you may select. Is your hair curly, kinky, straight, in locs, or relaxed? From there, you’re directed to a list of salons available to meet your needs — all of which understand how to approach black hair. Each salon is rated up to five stars and is accompanied by customer reviews at the bottom of the page. You book the exact service you’d like from the salon (which costs the same if you were to book directly with the salon — there are no upcharges or service fees), select a stylist, and then select a date and time. Swivel also offers a home-styling option for those who’d rather stay at home.

Through Swivel I met Mia-Shanelle. She came to my home at 7 a.m. on a Friday morning. In my living room, while she sewed row after row of curly extensions into my roots, we talked about the upcoming election, her newborn child, and the Magic Sleepsuit. For a while I fell asleep in my chair — not because I was bored, but because Mia-Shanelle re-created the same comfort I felt as a child in my aunt’s salon.

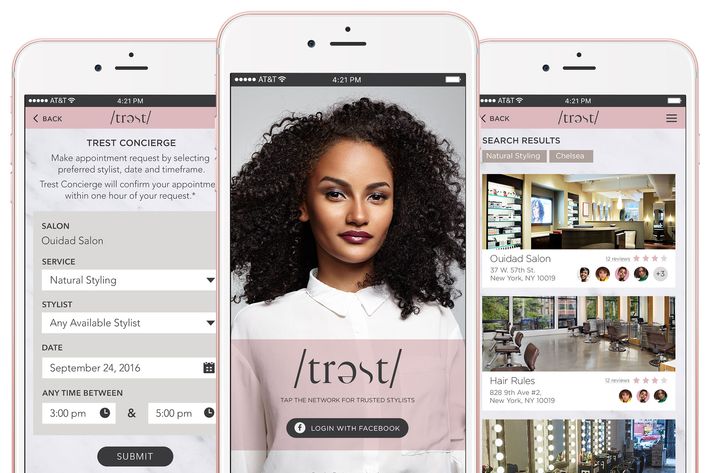

Swivel is not the only salon-booking app for women of color. Trest, which is marketed toward “textured hair,” launches on Monday. Like Swivel, Trest is packaged in a pretty pink app and connects clients with a network of salons. The app will be available to users in New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, and San Francisco, to start.

In a way, Trest operates as something of a salon social network. The app syncs with the user’s Facebook account to populate salon recommendations generated by their Facebook friends. For example, if your Facebook friend Melanie selects Ouidad and Hair Rules on her list of preferred salons, you’ll be able to view Melanie’s preferences as you decide where to book your next appointment. It’s a tool to help make the selection process less taxing. “You know who your friends with the good hair are,” says Daria Burke, Trest’s founder. “These are the salons she has chosen. Your search results are not only filtered by the service you’ve requested and your location, but also in rank order by the number of friends who’ve rated the salon. That’s where the magic happens. That’s where you start to qualify the quality of the recommendation.”

Of course, this depends on the number of your friends who actively use the app. The fewer friends involved, the more you’ll need to rely on the recommendations of strangers, who, like those in Swivel, rate salons using a star metric. The network of the salons available within the app was propagated by 200 of Burke’s friends and associates. They included both the obscure and the expected, but “trust me,” Burke quips, “they’re all great.”

Trest doesn’t offer in-home services, but, like Swivel, options run the gamut, from coloring to cuts, and the cost of services match what the salon would quote you directly. Taking the pricing structure into account, it would seem, then, that Trest and Swivel don’t make a profit. Burke explained it to me this way: “The priority right now is about product-market fit and getting traction. Ultimately there are four revenue streams that could come to bear. Direct referral where they [salons] would pay a commission to be on the app, or to be featured on the featured page; premium services, like reminder texts or emails if the salon wants to do a promotion; or a subscription or package model for customers.”

It’s an ambitious model, given the unpredictable nature of subscription enterprises. Then again, black consumers will spend an estimated $2.5 billion on hair care this year. One might say it’s a risk poised to bear extraordinary returns.

In the years before I became a beauty editor, I spent an incalculable amount of time apologizing for my hair. Each time I dared to try a new stylist, the words leapt from my mouth with a familiar cadence: “I’m sorry my hair is this way, that it’s thick, that it’s curly, that it requires a blow dryer and flat iron, that it’s attached to this black body.” At the time I didn’t recognize the absurdity in this practiced prostration. Hairstylists are required by law to complete a cosmetology program and pass a licensing exam. That they were unfamiliar and ill-equipped to style my hair was, in fact, a blight on the fabric of their competence and not to the fiber of my hair.

For many reasons, I’m no longer the apologetic, shy client I used to be. Working in the industry has injected a shot of confidence into my being. But for everyone else, there are apps like Swivel and Trest. A salon should feel like an extension of home, and funny enough, tapping the home button is now the best way to find one.