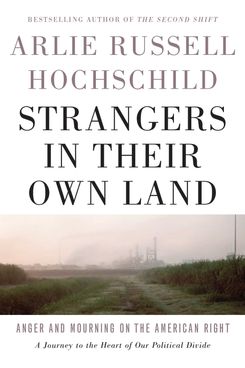

In 2011, Arlie Hochschild started five years of deep reporting in the deeply conservative, petrochemical center of Lake Charles in southwestern Louisiana. The University of California, Berkeley, sociologist’s goal was to understand what she calls in her recent book, Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right, the “Great Paradox”: Why do people who most need federal assistance hate the federal government? Why are the right-wingers and tea-partiers she interviewed — some of whom received federal assistance — so against welfare? The book also addresses another question that’s risen since its September publish date: Why did these rural Louisianians — and their peers across the country — help push Donald Trump into the White House?

The book has quickly become a primary text in understanding the bubbles that comprise America as it totters into 2017: The New York Times said it’s one of the books to help you understand Trump’s win; NPR said it’s a book needed to cross the political divide, along with Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me. (Correspondingly, Hochschild’s publicists were eager to share an advance of next Sunday’s Times best-seller list – Strangers slots in at 14 on the hardcover nonfiction list.) Like Coates’s, Hochschild’s work provides a window into the worldview of a group that is, for many people, the other.

The right-wingers, 40 of whom she came to know through in-depth interviewing and whom she refers to as “friends,” feel like they’ve been marginalized by declining wages, scorning liberals, and changing demographics. “My method was to take my own political and moral alarm system off, to say that the purpose of my talk was no longer to express my identity to others or alter the way other people saw the world,” Hochschild tells Science of Us. “The purpose was to elicit other people’s perspective and make them feel safe in my company, and safe in my intention.”

Through her interviewing — of characters like Lee Sherman, whose clothes he says burned off while dumping chemicals into the bayou for a plant; Madonna Massey, who thinks the Rapture is coming in the next thousand years; and Mike Schaff, whose living-room floor cracked when a drilling company cracked a giant salt dome deep beneath his home — Hochschild arrives at what she calls the “Feels As If” worldview. It goes like this: You, a white, Christian, aging man, are waiting in line for the American Dream. You work hard, you work long, yet the line is barely moving. And people are cutting in line ahead of you: immigrants, people of color, Syrian refugees. Even a brown pelican, the state bird, is placed ahead of you, since it “needs clean fish to eat, clean water to dive in, oil-free marshes, and protection from coastal erosion.” As Nathaniel Rich observes in his review, that means that the oil-rig worker is worth less than the oil-drenched bird. When she shares her account with her subjects, they light up: “I live your analogy,” Schaff told her.

The key, Hochschild says, was to be completely transparent about who she was: a liberal progressive from Berkeley, California. Prejudice cut several ways: People on the far right in Lake Charles assumed that someone coming from the North was going to think that they were “racist,” a bad person somehow associated with slavery and the brutal oppression of minorities. “They were allergic to the word,” she says, “and avoided the whole topic of race.” She also realized that something else on their mind — not to do with their racial prejudice, but a social-class prejudice of some liberals who would dismiss them (and thus their plight) as rednecks. Her subjects felt like they were in a defensive crouch; all they had to do was listen to coastal liberal comedians and know that they were looked down on.

If America and Americans are going to get less divided, it’s going to take some deliberate sensitization, in both the political and practical spheres. From all that fieldwork, Hochschild has two main prescriptions.

The first: Progressives need to understand that there are real cultural and economic issues that need to be addressed. “Just looking at the economics, the blue-collar class has lost out in globalization in the last 30 years. It bears repeating that they have been on the losing end. Loss of industrial jobs, automation. They’re really hit harder by automation than professionals and managers,” she says. “I think of them as the left-behind of globalization, and the Democratic Party hasn’t addressed that. These are the losers speaking up. These are real economic issues that Trump has tried, and perhaps falsely promised, to address.” When he talks about renegotiating deals, reversing the trade deficit with China, building a wall, it does speak to actual, lived economic issues. “The seriousness and reality of that discontent, it doesn’t just reduce to racism,” she says. “It isn’t just others getting ahead, they’re falling behind.”

Along with that, she says, blue-collar communities need to be reached out to in a constructive way. Maybe with the skills of a trained mediator, who could help get people to turn their alarms off and avoid spending the whole time insulting each other. She appreciates Living Room Conversations, a nonprofit created in 2010 by MoveOn.org cofounder Joan Blades, where people of opposing viewpoints agree to meet over the course of months and see what they can agree on — like, say, reducing prison populations. “That idea could be expanded through the church, schools, unions,” she says,”if it were handled right, to depolarize ourselves.”