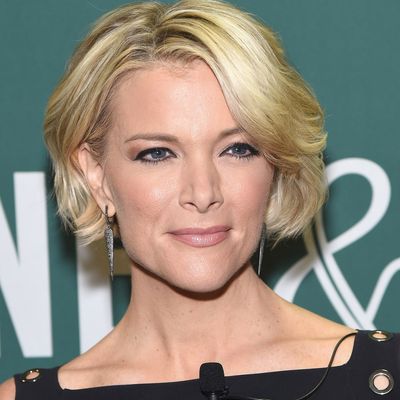

In her new memoir, Settle for More, Megyn Kelly — Fox’s steely-eyed prime-time warrior — reiterates that she is not a feminist.

“My problem with the word feminist is that it’s exclusionary and alienating,” writes Kelly, who argues that the term has become overly associated with liberal politics. “Why do we have to make the most divisive issues a key part of the feminist platform?”

Then again, Megyn Kelly has done a lot of things that smack of the dreaded “F” word. On her incredibly popular news show, The Kelly File, the host has become known for challenging Republican Party doctrine with what the Times’ Jim Rutenberg has dubbed “Megyn Moments”: defending maternity leave, advocating for working women, and eviscerating misogynists on air (although she upholds the GOP status quo far more than she challenges it, these moments of dissent have made her a viral star). Her status as feminist lightning rod grew when she was targeted by Trump after pressing him on his history of sexism, making her a potent, if reluctant, symbol of his war on women. At the same time, Kelly has often done things that contribute to women’s oppression; she called the gender pay gap “infantilizing” and a “meme,” has derided the movement for affirmative consent on campus as being anti-men, and regularly proffers racist stereotypes (not to mention insisting that “Santa is white”) just as harmful as those espoused by her Fox peers.

Still, liberals, perhaps grateful to hear from someone who doesn’t always toe the party line, have rushed to claim Kelly as a feminist hero, a breath of fresh air wafting through the dank chambers of Fox News. “Kelly has emerged as an unlikely feminist warrior” writes Emily Nussbaum in The New Yorker. Others are less enthused. “Megyn Kelly Is Hardly A ‘Feminist Icon,” argues Media Matters. (Conservatives have similarly strong feelings.) Indeed, nobody seems to know what to make of Kelly, a confusion that feels tied up in feminists’ broader struggle to understand how so many women in this country could have cast their ballots for President-elect Trump.

Yesterday, I picked up Kelly’s memoir, Settle for More, in hopes of getting a better sense of who she really is. The book covers her middle-class upbringing in Syracuse, and her steady rise through the worlds of corporate law and TV broadcasting. She comes across as a hard worker and overachiever gifted with natural charisma and boundless confidence (at one point, Kelly is turned down for a job because she is “too perfect”). She has trouble making female friends because she’s seen as intimidating and aloof, which she attributes to a protective guard she put up in the wake of a teenage bullying incident and the death of her father when she was a kid. She’s a guys’ girl who is used to hanging out with powerful men and has no problem with “locker-room talk.” She hates political correctness. She’s constantly underestimated and objectified because of her looks, which she has learned to use to her advantage. When she comes up against workplace sexism — which she has, plenty — she confidently shuts it down, but often defends its perpetrators as being from “another generation.”

Ideologically, Kelly is a tough nut to crack. Throughout the book, she never comes out as a Republican or Democrat and refuses to share her views on abortion (which she justifies by saying she wants to remain an impartial journalist). Her feminist credentials, too, are all over the map. In one breath, she’ll argue convincingly for the importance of paid maternity leave; in the next, she’s chastising her younger self for playing into stereotypes about “hysterical women” and arguing that women with high voices should consider voice training.

Some of this fence-sitting is arguably a strategic move; Kelly has both a liberal and conservative audience to appease, and would risk alienating her base and being charged with bias if she appeared to lean too far to the left. Yet a lot of Kelly’s worldview comes with the undeniable stink of privilege: an easily digestible mantra of “female empowerment” that fails to acknowledge the full breadth of institutionalized sexism and how it intersects with other types of oppression.

Kelly is a friend of Sheryl Sandberg’s, and one can see the Lean In stamp all over the book. “I love how her brand of feminism highlights the things we can all agree on as women — empowerment, advancement, equality, sisterhood — and steers clear of the more divisive issues,” Kelly writes. “Who gives a damn what label we use, as long as we are living a life that supports other women?” But which women does Kelly support? It’s clear that her beliefs about which women can achieve are inextricably tied to her own trajectory, and her ability to rise to the top despite obstacles. (Oprah “never made a ‘thing’ of her gender or her race,” Kelly says. “She just wowed us all.”). But lots of women — particularly women of color and low-income women — try very hard to “settle for more” (once they’re finished “leaning in” and trying to “wow us all”) and find that sheer force of will isn’t enough to transcend a system that has always been rigged against them. Sure, Kelly recognizes that women have to work twice as hard and be twice as good, but she sees that less as an inherent problem with the system than a noble hurdle that can be overcome with simple hard work. I cracked the glass ceiling, Kelly implies. Why shouldn’t you?

The end of the book deals with Trump’s campaign of harassment against Kelly and the revelations that former Fox chairman Roger Ailes was a serial sexual harasser who targeted Kelly and many other women at the network. In both instances, Kelly vacillates between demonstrating a clear understanding of how women are systemically oppressed and reverting to the only-woman-in-the-room attitude that recurs throughout the book. At the first GOP debate, Kelly boldly called out Trump for his abuses against women, and continued to press him throughout the campaign, all while enduring constant harassment and threats. And yet, she uses the experience as an opportunity to call out “political correctness.” “Adversity is an opportunity, and one that has allowed me to flourish,” she writes. “Imagine if I’d had no conflict prior to this. If I’d had no practice in how to shore myself up. If I’d only existed in my ‘safe space’ with my ‘trigger warnings.’ I’d have had no means of coping,” she declares. Because she coped, Kelly seems to imply, other women can too — even though it’s clear she would never wish this sort of abuse upon anyone else.

When it comes to the Ailes case, Kelly advocates for reforms in how we deal with workplace sexual harassment and argues admirably against victim-shaming, describing how she encouraged other women to come forward. “The entire structure was set up to isolate and silence [victims],” she writes. “The more we criticize harassment victims for their understandable reluctance to go on the record, the more women we’ll shame into silence forever.” But then, in the next breath, she returns to this sort of exceptionalist thinking: “Anyone being harassed needs to remember that no is an available answer. Roger tried to have me and I didn’t let him.” (Although she generously admits that saying no “isn’t foolproof.”)

Which leaves us with the question: What to make of Megyn Kelly? I suspect there are many women in this country who ascribe to her brand of sorta-feminism: who want to fight back against gender inequality and discrimination, but who feel excluded from mainstream feminist ideology because they disagree with some of its inviolable principles like access to abortion. Which is not to say we should cease our battle for a more inclusive, intersectional feminism that lifts up all women, but just that we should think about reasonable ways to find common ground with women we disagree with. Kelly may be an imperfect messenger, but by virtue of her bipartisan credibility, she also has the opportunity to introduce feminist ideals to an audience that might otherwise reject them: to open women’s eyes to sexism and inspire them toward their own “Megyn moments,” even if they aren’t ready to reckon with the full extent of its impact.