In a recent interview, Oprah asked Michelle Obama about whether her husband had delivered on his campaign promise of hope. The First Lady said yes, emphasizing how Barack was always the levelheaded adult in the room, reassuring America when tragedy stuck — again, again, and again. Though she never mentioned Trump by name, she said that she could “feel the difference” now that she’s on her way out. “We’re feeling what not having hope feels like,” she said. “You know? Hope is necessary.” She added: “Barack didn’t just talk about hope because he thought it was just a nice slogan to get votes. I mean, he and I and so many believe that if you — what else do you have if you don’t have hope?”

It’s devastating to hear the outgoing First Lady, who’s become a “singular voice” in American politics, express such anguish. (Naturally, Trump maintained that she misspoke.) Like the first act of a dark, modern folk tale, it’s a sign that darkness has swept across the land.

David Biello, who just authored a book on climate change, said in a recent interview that “we did just get a little more doomed.” There’s “hopelessness” in Chicago over relentless gun violence, and “deaths of despair” are driving down the life expectancy of whites. This very publication declared that with the election, the republic repealed itself.

In light of all this, is it naïve to be optimistic? Foolish to harbor hope? Three modes of inquiry – neuroscience, history, and psychology – supply complementary and contrasting perspectives. By putting them together, you can start to see what good hope and optimism might do you. And the country.

Neuroscience: We’re born optimistic.

Perhaps part of the reason that everyone is so relentlessly disappointed by the world is that it’s programmed into our very brains. According to Tali Sharot, the principal investigator at University College London’s Affective Brain Lab, an “optimism bias” is baked in. It’s “expecting things to be better than they are,” she says, like if you just know that you’ll make more money in the stock market or at the poker table than is really likely. “What’s surprising is we have positive expectations even in the face of reality,” she says.

Take the Belief Update Task, in which Sharot and her colleagues would present participants with 80 or so unsavory life events, like a domestic burglary or getting kidney stones. Participants would then estimate the likelihood of their experiencing such a thing themselves. Then they’d be told of the real-life statistical chances. Afterward, they’re asked to estimate the likelihood again — and inevitably, participants would amend their original estimate more with good news (that kidney stones, for instance, were less likely than they first thought) than when they get bad news (that the kidney stones are more likely). For most people, she says, this is because the brain is actively regulating the reception of negative information. Even more intriguing: People whose brains have more white-matter connections between areas related to inhibition and error-monitoring and areas related to emotion and motivation would be more extreme in the way they discounted bad news and readily received good news.

It helps to explain “illusory superiority,” the humbling and pervasive psychological finding where people think they’re better than they are at just about everything, whether it’s driving, their own attractiveness, making moral judgments, or knowing what makes a joke funny or a food healthy to eat.

The optimism bias makes evolutionary sense, she says, since it reduces anxiety and gets people exploring their worlds and living healthier lives. Your ancestors were your ancestors because at least in part they were optimistic (while also a bit anxious). When I asked about whether one can be rightly optimistic about national politics in the U.S. or U.K., she simply said no: It’s like the financial markets — one person can only make small changes. From that perspective, you might be better suited to deploy your optimism at a hyperlocal level, like your goals for personal growth, fitness, and the like. But civic change, as the long arc of history will tell you, does have a way of bubbling up.

History: You need to see how hope has worked.

With Hope in the Dark, Rebecca Solnit established herself as the chief American historian of hope. A philosophical, lyrical assessment of popular action, the book contends that all revolutions start out as revolutions of the imagination. Correspondingly, to have a well-stocked imagination is to be fluent in the past. First published in 2004, the book is a reaction to — and document of — Bush-era America. It caught fire again after this past November 8. Publisher Haymarket Books tells Science of Us that they’ve sold 8,000 copies since the election, and since it shows no signs of slowing down, they’re reprinting another 20,000.

Solnit defines hope against the certainty offered by optimism (it will all be fine) and pessimism (nothing will be fine). It’s humility, a tolerance of ambiguity, and a willingness to act all rolled into one. “People have always been good at imagining the end of the world, which is much easier to picture than the strange paths of change in a world without end,” she writes. And also: “Despair is also often premature: it’s a form of impatience as well as of certainty.”

If one is to be hopeful, then one needs to have a sense of the victories of progress that have indeed come to pass. It’s cultural amnesia to forget how quickly standards can change. Solnit calls the reader to remember that gay bars used to be raided and homosexuality illegal, that women fought (at least) 75 years of suffragette struggle to get the vote. The abolitionist movement started in 1785 in a London print shop, she recalls, and by 1833, the British parliament passed the Slavery Abolition Act. “It required imagination, empathy, and information to make abolition a cause and then a victory,” she writes. “In those five decades antislavery went from being radical to being the status quo.”

If that soaring rhetoric doesn’t get you, maybe the long-term trends will — this is the argument of Harvard cognitive scientist Stephen Pinker, who has a side gig as a historian, the fruit of which includes 2010’s The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined. “Look at history and data, not headlines,” he told Vox recently. “The world continues to improve in just about every way. Extreme poverty, child mortality, illiteracy, and global inequality are at historic lows; vaccinations, basic education, including girls’, and democracy are at all-time highs.”

This echoes the points that he emphasized to me before: that the drivers of human progress are, in many cases, getting less politicized — they’re neutrally, empirically verifiable. There are, in global health speak, “evidence-based interventions,” like the insecticide-treated bed nets in Africa that cut down on the deaths of children under age 5 by 20 percent, or deworming efforts in school children that have big impacts not just academically — like an increase in school attendance — but a decade down the line, with more hours worked, greater earnings, and fewer missed meals compared to a control group.

Pinker also praises economic development: The booms in India and China have made millions of people wealthier and healthier without leaning on old recipes for social enrichment, like conquering other countries or radically redistributing wealth. Time itself is a reason to be hopeful, too: “As my own cohort of baby boomers (who helped elect Trump) dies off and is replaced by millennials (who rejected him in droves), the world will become more tolerant,” he said.

Psychology: Without being woo-woo about it, hope changes lives.

If you want to know how hopeful you are, take the Adult Hope Scale (pdf), built to measure the University of Kansas psychologist C. R. Snyder’s “cognitive model of hope.” Snyder was the guy in developing hope as a psychological construct, and he pioneered the field from the late 1980s and into the early 2000s — all while living with chronic pain — until his death by cancer at age 61. In a review published near the end of his life, Snyder concluded by writing that in studying hope, he had also “observed the spectrum of human strength.” It’s like “the rainbow that frequently is used as a symbol of hope,” he continued: “A rainbow is a prism that sends shards of multicolored light in various directions. It lifts our spirits and makes us think of what is possible. Hope is the same — a personal rainbow of the mind.”

To Snyder, hope reflects the interaction between your goals, your sense of personal agency, and your pathfinding ability. It’s your ability to link your present to imagined futures.

Snyder and his peers found a ton of correlations between high hopefulness and diverse measures of success. Studies indicate that highly hopeful college students get higher GPAs and are more likely to graduate. They also perform better in track and field, cope better with injuries, and have greater psychological “adjustment”; that is, they are better able to deal with the cards that life deals them.

The mechanism, Snyder thought, had a lot to do with how the highly hopeful conceive of goals and how they’ll get there. To Snyder, the highly hopeful are canny “goal investors”: They diversify the things they want out of life, and sub one in when another can’t be reached.

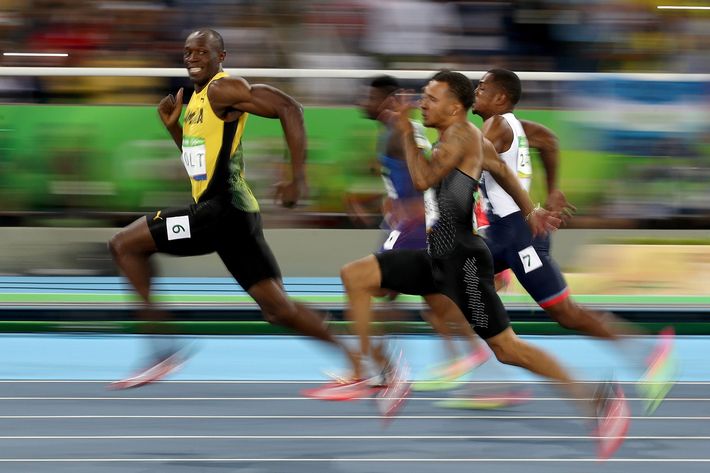

Similar to Stanford psychologist Carol Dweck’s “growth mindset,” highly hopeful people see barriers as challenges. According to Snyder’s work, this comes through in subjective experience. If you’re high in hope, then challenges make you feel excited and confident, bouncing around and dancing like Usain Bolt before he wins a gold medal. That happy-go-luckiness translates into a flexible imagination: Since you feel so hopeful about your chances, your mind wanders around, looking for ways that you’ll succeed. It’s like what the poet Robert Sylvester Kelly once said: If I can see it, then I can do it / If I just believe it, there’s nothing to it.

The low-hope condition is much more immobilizing, and should be familiar to anyone who was a wallflower at a middle-school dance. Snyder hypothesized that being low in hope meant that as soon as a problem started getting hard, confidence would flag for the low-hoper, as they turned inward, told themselves they were bad at it. And therein lies the savage irony of hope: If you’re low on hope, you’ll be less focused on the task at hand, compounding the issue, kind of like how being more biologically sensitive to threats makes people more easily distracted from their work, or how Atlanta Hawks center Dwight Howard refuses to take jumpshots because they might not go perfectly. It rhymes with the organizational-psychology advice to reframe the anxiety you feel about giving a talk or singing karaoke as excitement: Your body is already in high alert, so instead of spending your attention cogitating about what could go wrong, you think about what could go right.

This is a point Synder returned to in his review. He shared that he was often asked by incredulous interviewers if he’d rather have a low-risk pessimist or a risk-taking optimist piloting his next flight. To him, the choice was clear: “Do we really want the pessimistic pilot—filled with anxiety, tension, worry, sadness, rejection, anger, self-criticalness, and profound uncertainty—to be at the controls when our jet is landing during a thunderstorm?” he wrote. “Not me. I want a high-hope pilot in that cockpit.”

This seems to be the function of the audacity of hope: Even if it risks the vulnerability of your candidate losing, it’s an attitude that generates power, whether personally, professionally, or politically. After all, much of life is contemplating, pursuing, and completing goals — what you might colloquially call dreams — and hope is the fuel that gets you there.