New York State legalized abortion on April 9, 1970, not quite three years before Roe v. Wade came down. It was the second state to do so, after Hawaii, and the first to allow abortions for nonresidents. The State Assembly vote had been close in Albany — a tie, in fact — until one legislator rose and dramatically changed his vote from no to yes, citing his children’s pleading and his conscience. (Bedlam broke out in the chamber.) A month before the new law took effect, New York published a guide to the state of medical affairs. “No one knows how many girls and women from the city, to say nothing of the rest of the country, will begin demanding the termination of unwanted pregnancies,” wrote Lael Scott. “Incredibly, no one knows much about what facilities exist to deal with their distress except that they are grossly inadequate. And no one knows how long it will take the medical profession to sort out its own conflicts and respond to this new and urgent need.”

Over many pages, she walks readers through the new landscape, focusing much of her reporting on an argument among doctors about whether stand-alone clinics are a net positive (owing to their accessibility and efficiency) or a risk (because they’re not hospitals). She addresses the question of Catholic physicians and hospitals, who were allowed to opt out. And she turned up a split among African-American radicals: “First birth control, and now abortion. These are Whitey’s ways of generating black genocide,” is how she paraphrases one side’s argument. One doctor told her, “I’ve seen black militant men get booed down by women at meetings when they’ve brought up the genocide issue.”

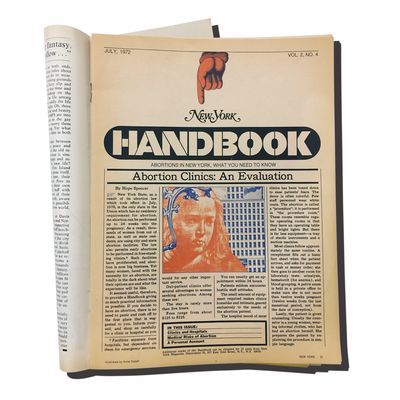

Scott’s inkling of New York State as an abortion destination was prescient: A pipeline bringing women across state lines soon developed. A freelance journalist named Hope Spencer saw that the new clinics were underregulated — “assembly lines,” she recalls today — and researched and reported another guide to legal abortion. It took the form of a handbook, with evaluations of clinics and hospitals, and ran in the July 24, 1972, issue. Abortion “had become a big business,” she explains, adding that even cabdrivers had been spotting young female out-of-towners and fleecing them. (One estimate in 1971 had 84 percent of legal American abortions taking place in New York State.) Spencer listed facilities in two groups, for abortions before and after 12 weeks. A doctor contributed a straightforward account of the risks inherent to each type of abortion. A woman named Beth Richardson — married with one young child, happily — wrote an experiential memoir of her own abortion, talking about her anxiety beforehand and her relief afterward. The tone of the package is completely businesslike: This is legal, and here is how and where to avail yourself of it. Spencer recalls that the issue sold out on newsstands.

It was her second story in New York, and the previous one had not been so dispassionate. “The Case of the Missing Abortion Lobbyists” ran in the issue of May 29, 1972, and it’s a firsthand account of a moment, earlier that month in Albany, that’s almost forgotten today. Two years after legalization, a bill had come before the State Assembly to re-prohibit abortion. Right-to-life activists had their act together; the pro-choice side had been disorganized, its protests thin. “I am nobody’s idea of a veteran lobbyist,” wrote Spencer. She’d never been to the state capitol before. And she was scathing: “Where were all the other doctors, the young doctors who are specializing in abortion techniques? Where were the … huge counseling staffs from the outpatient clinics whom I’ve watched give hours of sincere attention to abortion patients each day? And where were some of the 200,000 New York State women who have had legal, safe abortions since July, 1970?” Spencer described tromping up and down Albany hallways with a group of activist-lobbyists, getting lost and getting nowhere.

Her alarm had been justified. The bill not only passed the Assembly; it also passed the Senate, and legal abortion survived in New York on the stroke of a Republican governor’s pen. “Only the grace of a Rockefeller veto prevented the repeal of legal abortion in New York. That reprieve certainly wasn’t the work of the women, who have the most to lose.” Although Spencer could have tried to pull some strings — her full name was Hope Aldrich Rockefeller Spencer, and the governor, Nelson Rockefeller, was her uncle — she didn’t tell him she was there that day. Nor did she try any family back-channel approach. “I didn’t operate that way,” she says.

*This article appears in the January 9, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.