Tish Bellomo looks to be in her fifties, but it’s difficult to know for sure — there are few pictures from the past forty years of her or of her sister Eileen, who goes by “Snooky,” without both of them sporting wild, fluorescent-colored hair. News clippings from the eighties hanging in their shared office show it layered, feathered, and back-combed into a fiery mane. At the moment, hers is bright pink with a green streak at the front — a nod to the hair-dye brand that made her and her sister famous four decades ago, and the company they still run today: Manic Panic.

Today, Manic Panic is so synonymous with wild hair color that the company name has turned into a verb: to Manic Panic is to dye someone’s hair Wildfire Red or Atomic Turquoise or Cream Purple Haze. Very few cultural institutions could withstand the march of the time the way Manic Panic has, at least not without significant revisions in its brand meaning, implications, and ownership. To be embraced by punk culture and survive for decades without eliciting the inevitable accusation of “selling out” means that Tish and Snooky have created something very special indeed.

In the mid-seventies, Tish and Snooky were living in the East Village and spending their evenings as backup singers for the band Blondie at CBGBs. The punk scene was in full swing and the East Village was inarguably at the heart of it. Record stores and clubs sprouted from the old hippie storefronts, even as Hare Krishnas in Tompkins Square Park were arrested for playing their bongo music too loudly. Within a few years the park would become such a notorious center of disorder that an attempt to clear out the homeless population, many of them resident anarchists or drug dealers, caused the infamous Tompkins Square riot.

As a movement, punk had a lot in common with the hippies of a decade earlier: the same youthful rebellion, the provocative clothing and ostentatious hairstyles, a relaxed attitude toward drug use, and a do-it-yourself approach to music creation. With bands being formed faster than they could be named, supplying the music itself was not a problem. Supplying the gritty, urban trappings of a punk lifestyle was a little more difficult. Leather, spikes, stilettos — all had few mass manufacturers in America at the time. When fellow scenesters started asking the sisters where to buy their signature style, Tish and Snooky decided to supply it.

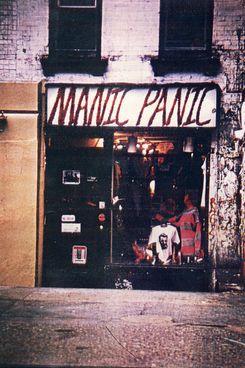

They borrowed $250 from an aunt and raided the same amount from savings Snooky had cobbled together working for a department store. Their new punk-clothing boutique, a small storefront on St. Mark’s Place, was given the disorder-inspired name “Manic Panic” at the suggestion of their mom, an art therapist at a Bronx psychiatric hospital.

“We used to go to stripper stores,” laughs Snooky, recalling how they sourced the store’s inventory.

“We found these great stashes of all these pointy-toed Beatle boots that no one else had. We found a big stash of black jeans. Everybody would hear about it and come for them,” says Tish. “At the beginning, our fans and our customers were basically all the bands that were playing at CBGB along with us. They were our friends and neighbors.”

Having no business experience forced them to rely on their own taste. “People would try to sell us stuff that they told us would really sell well. Maybe it would have, but if we didn’t like it, we wouldn’t sell it. We only sell stuff that we would wear,” says Snooky. “Johnny Thunders [came in], trying to sell us a saddle because he wanted money. We wouldn’t take it, because we didn’t want to sell a saddle.

“I wish I had that saddle now,” she adds.

Also into the shop went accessories, records by underground artists, fan zines, and, after one particularly fruitful buying trip to the UK, a line of bright, semipermanent British hair dye. Tish had been using it to dye her own hair, and, within weeks of offering it for sale, so was a respectable proportion of the East Village.

People were paying attention but not everyone liked what they saw. “A guy in a Rolls Royce pulled over on the sidewalk just to tell me that I looked absolutely ridiculous. [It] was so disturbing to him that he had to say it twice!” remembers Snooky. On the opening night of the Mudd Club, an alternative nightclub in Tribeca, Tish’s hair attracted unexpected attention when a group of suburban kids got out of their car to pick a fight. The altercation ended with Tish getting punched in the face. She was knocked out cold and finished the night in the hospital. “I hid it from my mother until she read about it in the paper,” she remembers.

Punk culture was never about being palatable, however, and in little time, the hair dye was an international sensation. Shoppers were making trips to Manic Panic from uptown, then from out of town, and then from Japan and the Netherlands. With the cachet of the punk movement behind them, the trip for many was likely as much about the pilgrimage as about the product. “People would read about it and come from all kinds of exotic ports of call. Like New Jersey,” laughs Snooky. “All these people started coming in, and at that time, we had hardly anything to sell because we had hardly any money. I was like, oh, my God. What’s going on? Why are all these people coming? We had to scramble and invest any money we made back into more stock, and keep filling up the store, because it was pretty empty.”

“Around Halloween, there was a line out the door and [we] could only let people in a few at a time because the store was so packed. That’s when we knew we were on to something,” she recalls.

Members of the B-52s spoke fondly of making regular pilgrimages. So did The Ramones. Cyndi Lauper made the dye part of her signature look just as she landed her first record deal. Says Tish, “Our store wasn’t just a store. It was like a clubhouse, a hangout for people, like a social scene where people would come because it was cool. It was this gathering place for bands and fans.” On Christmas Eve they would stay open late, and friends and musicians would pour in with wassail and cupcakes. “Everybody would get all emotional and teary,” remembers her sister. As a concept, it certainly evokes what their hippie counterparts would have called a good vibe.

Authenticity is the holy grail of every fan object; the goal of every marketing platform. It’s the glue that allows a group of otherwise completely normal people to devote parts of their lives to an inherently commercial object. Whether that object is a celebrity, piece of media, or product, fandom relies on a belief in the good intentions of its owners. By buying into what Manic Panic means, fans are trusting its makers with a very personal piece of their identity. It’s a hard bond to fake, and an impossible one to fake for very long, not even with vast amounts of market research and funding. And it’s totally impossible to “sprinkle some authenticity” over a product whose origins and ownership are suspect. “People really like that it’s a company that’s founded by punk rockers, not some business people who want to cash in on a trend,” says Snooky.

Today, Tish & Snooky’s N.Y.C. Inc., the sister-owned corporation behind Manic Panic, concentrates primarily on hair dye, and operates out of an office in Long Island City. The New York City clothing store is long gone, a victim of Manhattan’s rising rents and the brand’s need for warehouse space, but there’s still a small retail area near the front for those pilgrims willing to make the trip to Queens. Inside, one wall is covered with tributes and gifts from grateful fans. One customer has sculpted them a giant tub of Manic Panic. Some fans make them handmade jewelry, others make paintings, many of them portraits. “They’re a little scary,” admits Tish, but she and her sister hang them up anyway.

There are also plenty of notes about personal experiences. “There was one girl who wrote to us and said she was suicidal. She dyed her hair, and it made her so happy, and took her mind off of her problems. It just made her feel good,” says Tish. She recalls one elderly Canadian woman who reported that she had felt invisible and lonely before she dyed her hair purple: “She said it changed her life. All of a sudden, people talked to her and wanted to take a picture with her. Everybody was friendly to her. She just had so much fun. It was just the sweetest thing.”

“It really does change the way you feel when you change your hair color. I love my hair pink. I just love it. When I come into work here, I look around. At least 50 percent of the people working here have beautifully colored hair. It just makes me feel so good every morning. It just puts a smile on my face. When I see all the pretty colors, it just makes me kvell,” says Snooky.

The memories of punk’s early days may remain today, but there’s a key difference in how contemporary Manic Panic fans interpret the hair-dyeing experience. For one thing, the meaning behind crazy-colored tresses has become much more diverse. Today, it would be impossible to pigeonhole someone with a bright green dye job. He might be showing solidarity with urban youth, or it might be St. Patrick’s Day. A band member might dye her hair orange and blue to show her allegiance to alternative social norms, but she just as easily might be a fan of the University of Florida’s football team. Manic Panic is less a story of mass co-option and more a history of intense personalization. Modern fans use the product for the same purpose as their punk predecessors — to show off their unique sense of style. But the definition of who’s allowed to be unique — and what unique means — has expanded.

Early fandom academics saw fan groups through the rose-colored glasses of utopianism, the concept that fan groups are a safe refuge away from mainstream society for the disenfranchised and misunderstood. By the ‘80s, academic theory had taken a more Machiavellian tone, explaining that fans use their group membership to create a subsection of society where they have a chance to be on top. In the paraphernalia of punk culture there are certainly elements of the latter — the “poser” epithet popularized in the ‘80s (from the French poseur, pretending to be something you’re not) is a classic method of pulling rank over those “beneath,” marking out space in the fandom’s hierarchy and drawing a distinction between ourselves and lower-status members, especially those of the wrong gender, race, or class. Yet, when it comes to hairstyle, the mainstreaming of unusual dye jobs has been largely embraced, even by many who were part of its original punk genesis.

As a brand, Manic Panic seems free of much of the usual baggage that accompanies most multi-decade phenomenon. It successfully survived losing its physical claim to authenticity, the lease on its original store, with very little fan backlash against its products. It has maintained its clout despite its modern-day availability in mass market stores such as novelty chain Spencer’s Gifts and teen clothing store Hot Topic. There have been occasional licensing deals — a line of hair salons in Japan, a few cosmetics, a brand of wine, and an occasional T-shirt — yet, in general, the name Manic Panic is still synonymous with the dye that Tish and Snooky made famous.

“We’re still here at the business every day after 37 years,” says Snooky “We’re not letting somebody else take it or run with it. We’re afraid somebody wouldn’t do it our way.”

Adapted from Superfandom: How Our Obsessions Are Changing What We Buy and Who We Are by Zoe Fraade-Blanar and Aaron M. Glazer. Copyright © 2017 by Zoe Fraade-Blanar and Aaron M. Glazer. Reprinted with permission of W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.