Four days before she died in 1921, the young American actress Virginia Rappe walked into room 1219 of the palatial St. Francis Hotel in San Francisco, searching for a bathroom. The hotel was loud with tinny jazz from a Victrola and the clinking of cocktail glasses, the air dense with cigarette smoke. A man quietly followed her into the room, locked the door, and threw her onto the bed, falling on top of her. It was the last thing Rappe remembered before losing consciousness during an incident that became the first major Hollywood sex scandal, a case that in some ways prefigured the current phantasmagoria of sexual predation roiling both politics and the entertainment industry.

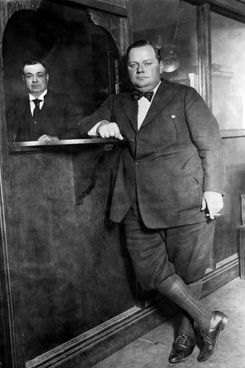

“He hurt me,” Rappe said to Alice Blake, a chorus girl at the party, upon awakening in the bed of her alleged attacker, Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle — he was among the most famous and handsomely paid silent film stars of the era, second only to Charlie Chaplin. Just before his encounter with Rappe, Paramount cut him a check for an unprecedented $1 million ($13 million in today’s dollars) to star in nine films. Four days later Rappe died due to a ruptured bladder, which Arbuckle allegedly crushed while he was on top of her. Arbuckle was arrested for first-degree murder, which according to California laws at the time, included the charge of rape.

The media had a field day with the story, condemning Arbuckle for his hedonistic lifestyle — which marked a departure in the coverage of silver-screen royalty. Typically Hollywood had been portrayed, mostly in newspaper gossip columns and fan magazines, as a carefree world of wealth and fun. Arbuckle epitomized that image: gamboling about his lavish mansion, being waited on by a passel of servants, driving a fleet of ostentatious cars. Now, scandalous headlines revealed he was addicted to morphine, had multiple affairs while married, and enjoyed throwing large, lurid parties like the one after which Rappe had ended up dead. Montana senator Henry Myers excoriated Hollywood’s “debauchery, riotous living, drunkenness, ribaldry.” The Baltimore Sun decried the “orgies of [the] film colony.” To Americans of the 1920s, the shock of discovering that Hollywood was a moral shadowland echoed, in kind if not degree, many reactions to the outpouring of allegations against Harvey Weinstein and his depraved brothers.

Interestingly, the scandal also unleashed waves of activism. At the preliminary hearings for Arbuckle, hundreds of women, many attired in their Sunday best, showed up to express solidarity with Rappe. It was an extraordinary scene for the time, women rallying against assault, and evokes comparisons to contemporary protests — the 2017 Women’s March chief among them. And just as today’s offenders find their television shows canceled, their movies pulled from distribution, many movie houses banned Arbuckle’s new films after his arrest. Los Angeles’ Million Dollar Theatre jettisoned his Gasoline Gus; San Francisco theater owners banded together to boycott all of Arbuckle’s films; and soon cinemas across the country followed suit.

Until this point, this tale is one of a proto-“awokening,” women demanding that a rapist be punished and the rest of society picking up the cause, if only, in some cases, out of puritanical outrage at Jazz Age “decadence” or the financial risk of choosing to screen an alleged murderer’s movies. But, of course, running parallel to the attacks on Arbuckle were those on Rappe. The actor’s defense team provided testimony that she may have had numerous illegal abortions; that she was a crazed, convulsing drunk who tended to strip when she got inebriated. One large film distribution company, Associated First National Pictures, even proposed suppressing films featuring her.

Arbuckle told two versions of events. In one, relayed to reporters before his trial, Rappe had had a few drinks, then suddenly became “hysterical” — a word that, then as now, served to dismiss women as crazy and unreliable. She protested that she couldn’t breathe, Arbuckle went on, and began stripping her clothes, throwing a “fit in the presence of everyone.” As a result, he said, two female partygoers took her into room 1219 and “disrobed” her. “I was at no time alone with Miss Rappe,” Arbuckle declared.

He changed his story at trial, perhaps because no one was able to back up his account of Rappe gasping for breath and shedding her clothes in public. In the new version of events, Arbuckle said he found the actress on the floor of 1219 vomiting from an already-ruptured bladder — though no evidence of vomit was found at the scene, and during the trial, a physician and bladder expert said spontaneous rupture of her bladder was extremely unlikely. Arbuckle admitted locking the door — similar to allegations, decades later, of Weinstein also locking a woman in a hotel room. One woman — whom Arbuckle had let into the room after the alleged assault — testified that the powerful actor had invited Rappe to the party promising “something big” for her film career.

With the main witness to the events dead, however, proving what had happened between Arbuckle and Rappe was especially difficult, and it took three trials — the first two ended with deadlocked juries — for a verdict to be reached. Arbuckle was acquitted. Afterward, the jury took the extraordinary step of reading a formal apology to the actor, one that is cringe-worthy in its casual sexism. “Acquittal is not enough for Roscoe Arbuckle,” the statement began. “We feel that a great injustice has been done him. … He was manly throughout the case and told a straightforward story on the witness stand, which we all believed. The happening at the hotel was an unfortunate affair for which Arbuckle … was in no way responsible.”

Though he was exonerated, Arbuckle had become a media bête noire. His films began to play again, but his career never recovered. As for Rappe, she more or less disappeared from public consciousness, though decades later a few sensationalized accounts of the scandal portrayed her as an alcoholic prostitute with syphilis or crabs. (There is no evidence that she had any venereal diseases.) Too often the stories implied she brought death upon herself as a sexually active woman.

Now more than ever, Rappe deserves to be remembered correctly. Born in Chicago in 1891, Rappe was not only an aspiring actress and model — one of the first women to make a living from what was then a new profession — but a fashion designer with a political consciousness. During WWI, she drew attention for her “peace hat,” which resembled a dove’s wings. “We should express our peace sentiments in our clothes,” Rappe told the Reno Evening Gazette. “If we believe in peace, why wear military jackets and soldier caps. Clothes influence our mind.”

In another testament to her belief in the power of fashion, she posed in tuxedos for an article that called for women to have “equal clothes rights with men.” “[I]t was Virginia Rappe,” the paper opined, “who first invaded the masculine wardrobe, carried off the Tuxedo coat idea and immediately converted it into a chic little street suit.” There is no record that Rappe ever called herself a “feminist” — a word that was just beginning to be used in the United States at the time — but why not give her that posthumous honor?