“There are lights skating up 51 stories to the copper tops of the buildings of the World Financial Center,” Julie Baumgold wrote. “They are lights from the windows of Merrill Lynch and Oppenheimer, Dow Jones and American Express. Each light is a Suit working late because of the stock crisis, guys in shirts looking at numbers and making late, painful calls, but downstairs, downstairs — it’s burning.”

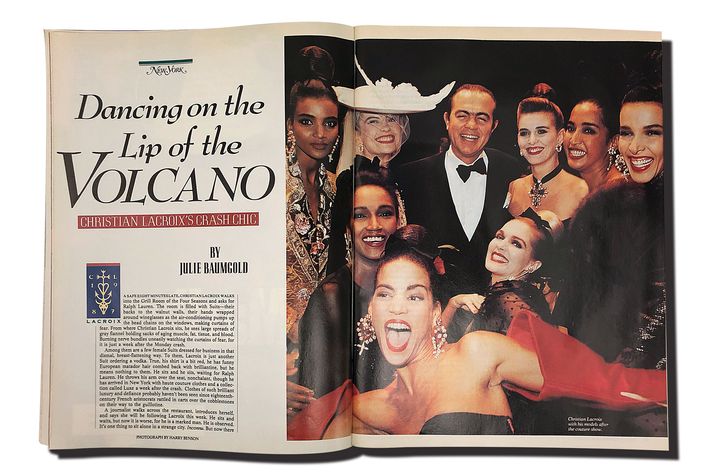

What was burning was Christian Lacroix’s first New York fashion show. It took place a week after what was already being called Black Monday, the day the Dow fell 22 percent. Baumgold had already been at work on a profile of Lacroix, the most-talked-about designer among the city’s socialites. His maximalist designs were ridiculous and funny, and could top $25,000 for a dress. “He had women on the Upper East Side wearing hoop skirts!” remembers Edward Kosner, who was then New York’s editor, and who had assigned the story to Baumgold (who is also his wife). “And,” he adds with a chuckle, “they didn’t look good in them.” But plenty of people in that world had enjoyed being seen as mini–Marie Antoinettes when the market was high and the money was rolling in.

So the show went on. The collection was presented at the Winter Garden in the World Financial Center, and thus provided the most delicious contrast imaginable for a writer (and a magazine) whose work often involves collisions of class and money. In homage to Tom Wolfe’s definitive New York story — “Radical Chic,” about a benefit party Leonard Bernstein hosted for the Black Panthers — Baumgold’s story is subtitled “Lacroix’s Crash Chic.”

It plays out in several other settings besides the show that night: an event at Bergdorf Goodman a few days before, a lunch at Jim McMullen’s, some scenes earlier and later. But the climax is there at the Winter Garden — Kosner recalls the weirdness of the traders’ peering down from the balconies high above — and so is the uncertainty of the days after the crash. Yet the response among the potential buyers is warm. Princess Gloria von Thurn und Taxis is thrilled; so is Veronica Hearst; so is Nan Kempner. “For now,” Baumgold wrote, “it seems as though everyone has taken the Bergdorf attitude. No one is pulling back, no one is hurting. Money lost, money left. There are no containers of English furniture at the docks going home. They are dancing on the lip under the yellowing 40-odd-foot palms. They sit down, knees tucked under the mango bengaline cloths among the roses forced to the bursting point on chairs slipcovered and tied with Lacroix hot-pink taffeta bows, and look out on the pyramid of steps lit with 3,000 votive candles … Everyone is forking up the first of the fruits de mer à la provençale when the fireworks start. Great exploding fireballs paid for by Revlon.”

And throughout the story, one extremely familiar name comes up: Blaine Trump — then the wife of Robert Trump, whose brother is you-know-who — was perhaps Lacroix’s best customer, and the hostess of the Bergdorf launch. Baumgold suggested that Blaine had finally emerged from the shadow cast by her brother-in-law: “THE WINNING WAYS OF BLAINE TRUMP, the Times had announced that morning. Never again would she be ‘the other Trump.’ ” (Donald and Ivana flit through the story, too.)

Since then, Blaine — through no fault of her own — has returned to her status as “the other Trump.” The Four Seasons, where the story opens, is gone. The grove of palm trees in the Winter Garden, wrecked when the building was crushed on 9/11, has been replanted. Lacroix, whose fashion house would file for bankruptcy in 2009, has moved on. (He redid the uniforms for Air France a few years ago, and there were no hoop skirts in sight.) The night Baumgold caught is now a period piece, one of those New York moments you can’t manufacture. Although the 1980s had another two years left to run, the idea of the ’80s ended that day, as the bubble definitively burst. “Sometimes the angels of journalism alight on your shoulder,” admits Kosner. “But you make your own luck — what’s that expression? The residue of design.”

*This article appears in the November 13, 2017, issue of New York Magazine.