Just before my annual review, during which I planned to ask for a raise, a friend returned from a trip to London and shared a book that gave me the confidence to do it: High Wages, a shop-girl novel written in 1930 by a woman who’s known as the Jane Austen of the 20th century, Dorothy Whipple.

It’s smart and delightfully funny and reading it felt like watching a Jane Austen movie — except rather than finding a man, the heroine is focused on opening her own dress shop. But before she can do that, she needs a raise.

Jane Carter, the book’s main character, is the 1912 version of an underpaid intern in the Devil Wears Prada fashion closet, or anyone who has lived in a converted New York City room/closet. She’s a poor, smart 17-year-old girl who loves style — and she sews her own clothes based on what she reads in Vogue, one of very few diversions available to her as a haberdashery-shop girl in provincial England.

Her boss is Mr. Chadwick, a stubborn control freak who denies her of rightfully earned money and keeps her salary at the lowest possible amount. Jane stands up to him multiple times to demand better conditions and pay, arguing with the kind of determination and humble persuasiveness that I hoped to convey in my own meeting. First, she decides to ask for a raise, and later she brilliantly convinces him of her value even when he refuses to listen:

“But, Mr. Chadwick, how could you expect me to stand by without speaking up for myself? In common justice, how could you? Would you be talked over the head of as if you were some creature without sense or a tongue — someone not quite clean or something — someone too inferior to be noticed? Would you? … I do think that I am worth more to you … Do you really think it would pay you to get rid of me?” she ended breathlessly.

Mr. Chadwick still gaped at her. She was amazing. To talk to him like this! And the queer thing about it was that she had worked it out all right. She was useful to him. She had made a difference to his business, and would go on making a difference. He knew he had never had a girl like her, and would probably never get one like her.

She wins. She gets the raise. She gets so good at her job that she wants to open her own business. It’s a feminist novel without any mention of suffrage or politics, depicting an intelligent young woman who loves shopping and dissecting the design of a pretty window display as much as she enjoys daydreaming about her career, or reading H. G. Wells surreptitiously at work below the shop counter. She befriends an older woman who becomes her mentor. She doesn’t think much about men or marriage at all.

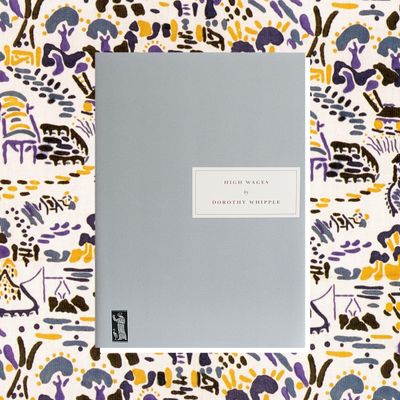

High Wages was lost from the publishing world and recently rediscovered by Persephone Books, a London bookshop that reprints work by neglected, mostly female authors of the 1900s. They reprinted Miss Pettigrew Lives for a Day, which became a best seller and later the movie starring Amy Adams and Frances McDormand. British women run the store (and break every afternoon for cake and tea!), selling a collection of 125 carefully selected titles mainly by women, all beautifully bound and numbered with silver book covers.

On my nightstand High Wages seemed the bookish equivalent of a silver tray in the dining room I aspire to have one day, a visually pleasing purchase in the vein of becoming a domestic goddess. This is in fact Persephone’s aim, according to their website: “Persephone books are all grey because — well — we really like grey. We had a vision of a woman who comes home tired from work, and there is a book waiting for her, and it doesn’t matter what it looks like because she knows she will enjoy it.” Each book comes with an inside cover designed especially for the book in colorfully patterned endpaper and a matching bookmark.

Minutes before my review, I stood in a conference room doing a quick power pose and read Jane’s words again. I walked into my boss’s office freshly inspired, ready to ask for my own wages. The book’s title is based on a Carlyle quote: “Experience doth take dreadfully high wages, but she teacheth like none other.” Dorothy Whipple is one such teacher. Persephone has nine more forgotten books by her.

If you buy something through our links, New York may earn an affiliate commission.