The first time Mary J. Blige saw herself onscreen in Mudbound, it made her cry. She’d become someone else, someone unrecognizable, yet — and she had to be told this at first — someone undeniably beautiful: Florence Jackson, a sharecropper’s wife in Jim Crow Mississippi who navigated the narrow path allowed for her life, seeing much but saying little. “The great surprise at Sundance was that people didn’t know it was her until the credits rolled,” says the film’s director, Dee Rees.

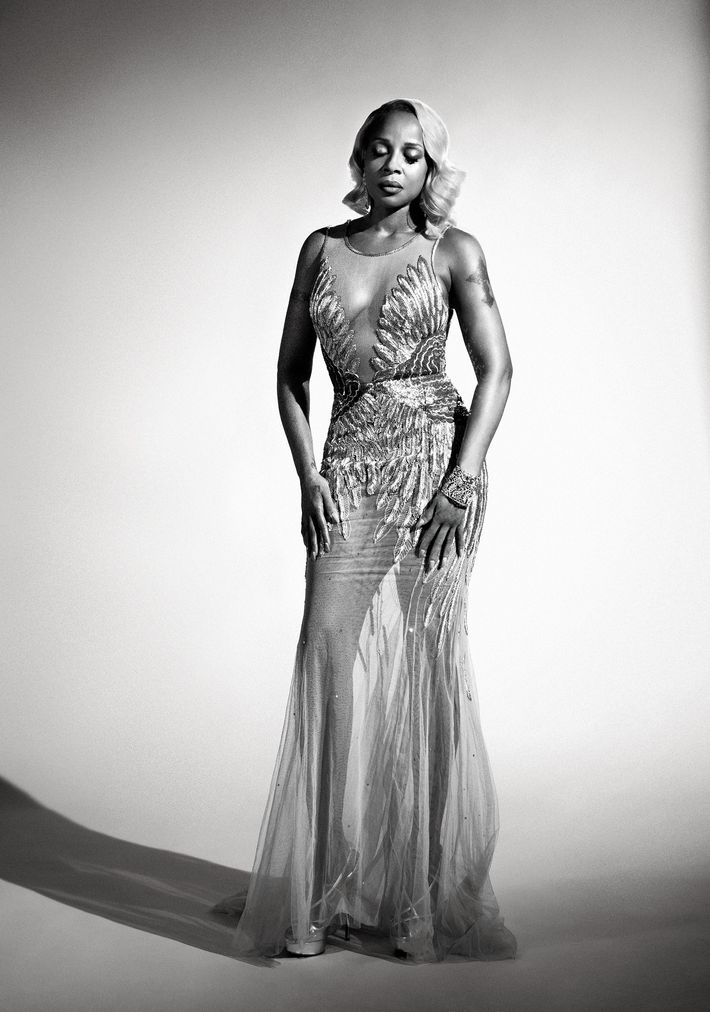

And now Blige is up for an Academy Award for the portrayal, so different from that other character she’s spent 25 years creating and, in a way, hiding inside: the bling-armored, blonde-wigged, Grammy-laden “Queen of Hip-Hop Soul.”

“I’m used to my nails now, and I’m addicted to lashes,” says Blige when we meet downstairs at her blandly luxurious Westwood high-rise — inside, all buttery tones, the polished tentacles of a Dale Chihuly chandelier floating above the lobby; outside, a fellow tenant’s Maserati SUV idling in the porte cochère. She hadn’t wanted to have me up to her apartment, so when I arrived, her REAL LOVE–hoodie-clad assistant led me through the building’s refrigerated wine cellar to what the concierge referred to as the “card room” for our conversation. “I’m Mary J. Blige. I mean, like, this is what I do. I wear wigs, I wear bob wigs, and I had to completely strip down to my own natural hair texture, which I’ve always been afraid of. Dee stripped me down all the way to what I truly am, and people were complimenting me. People were saying how beautiful I was. I didn’t know I was that beautiful for real. You understand what I’m saying? I didn’t know that.”

Blige is famous, but famous has never made up for anybody’s feeling of, as she once put it, “not being worth anything.” That’s her struggle, and because that is the struggle for many of us, it’s her bond with us, no matter how famous she’s become. Even people who grew up in far less dispiriting circumstances than she did — her father ran off; she was raised in Yonkers just as crack ravaged the community; a family friend molested her — understand that feeling, or have experienced some version of it. One of the revelations for Blige in making Mudbound was how much her R&B-star persona cosseted her, even as she sang — bled — achingly confessional songs, coming back again and again to the same lesson, the need to love yourself to be ready and able to love someone else.

“If I’m onstage every single night, it can’t just be for my fans. It obviously is for me, too,” Blige says. Her most enduring hits — “Real Love,” “Family Affair,” “No More Drama” — accompany our lives, whether or not we’re one of the millions who’ve bought a Blige album or exorcised our pain at one of her exultant concerts where, Rees says admiringly, “she’s reliving experiences.”

“I’m going to feel it like it was the first day,” Blige says. “I’m going to relive ‘No More Drama.’ I don’t have a choice. These things really happen, so they just turn up again. And if it’s healing for someone else, it’s therapy for someone else, it’ll be therapy for me as well.”

Rees knew Blige’s music, of course, but most of her acting was confined to roles in which she more or less played her pop self — like her turn as Viola Davis’s straight-talking hairdresser-confidante in How to Get Away With Murder (for the record, Blige confirms that, yes, she knew how to “sew in” a weave as she did on the show). Rees sent Blige the script for Mudbound after seeing her play Evillene, the Wicked Witch of the West, on The Wiz Live! in 2015, impressed by her willingness to throw herself into that character on live television.

It was a gamble for Rees. The Mudbound shoot was arduous — they filmed, with a tight budget, in the middle of the Louisiana summer. But Blige wasn’t the diva she could have been. She worked hard, knew everybody’s lines as well as her own, and became Florence so much that, Rees says, extras didn’t know she was Mary J. Blige. “She had this vulnerability and reserve,” Rees says. “She could feel much and withhold much. There were just moments of stillness and her silences — this dark commentary she could say under her breath. A lot of actors tend to be very aware of their surroundings. She would just go perfectly still, and she was in her head. Just sitting, thinking.”

“I hate pain, but I know how to deal with it,” Blige elaborates. “To do the assignment God has sent me to do, I have to live certain things. And unfortunately I’m constantly living it. You understand what I’m saying? It’s like trying to talk to a prison class, but you’ve never been to prison.”

She’s done her time with cocaine and alcohol troubles, money troubles, tax troubles. Much of which, judging from her lyrics and the facts of her life as she’s related them over the years, hinge on her inability to find a man who is trustworthy. She was on the verge of filing for divorce from her husband and manager, Kendu Isaacs, during the filming of Mudbound, but didn’t tell anyone on set. “It wasn’t anybody’s business,” Blige says. “I just kept it and gave it all to Florence.”

Today, when I meet her, Blige is wearing a blue Adidas tracksuit with red stripes, a DSquared baseball cap (“Their clothes are so hot.

I mean, so hot”), and white house slippers. “This is what I look like when I’m not on-camera. It’s all about being comfortable. If your feet are comfortable, you win,” she says, crinkling a plastic water bottle in her left hand and occasionally flipping her hoop earring over her collar, where it keeps getting caught when she turns her head. “If your feet hurt, you have to go home early. That’s what happened to me at the Critics’ Choice Awards,” which were held on her 47th birthday, January 11. “My feet started hurting so bad, I felt like somebody was cutting my toes off. I had to leave, and soon as I left, they brought me a cake. The other cast members were texting me, saying, ‘They just brought you a cake!’ ”

Her lack of instinct for femmed-up sexiness is only one of many ways she’s an unusual pop star. She was never going to be Whitney or Mariah, her contemporaries on the charts. She was a tomboy with born-and-bred-in-the-projects hip-hop authenticity — something her first producer, the then-19-year-old Sean “Puffy” Combs, recognized as soon as he met her. He’d show her how to wear that baseball cap turned backward. “What I loved about Puff is he immediately saw — I mean, instead of a tight dress, he put a baggy Armani suit on me with some Teflon boots. I wore a miniskirt sometimes, a pleated miniskirt, but I wore boots with it. But I hated skirts, I hated dresses, because I sit like this” — she leans forward, elbows on knees, legs spread. “I can’t sit like that with a miniskirt on.”

Her look and demeanor were also about “survival,” Blige says. “I worked with a lot of men and grew up around a lot of men. I didn’t want them to look at me like that. I kind of sat like them, talked like them, even subconsciously, so they wouldn’t look at me like I’m a girl.”

Not that the tomboy didn’t eventually evolve into something more glamorous. “It took me a long time. I didn’t want to wear lipstick and all this stuff,” she says. “I’d fight not to wear these little shorts [in videos], and I’d end up wearing them and the video would be great. And you’d be like, Okay, that’s not bad, and you start to grow.” It’s a kind of dueling persona she has: In the video she did of the remix of “Love Yourself” last summer, with A$AP Rocky, half the time she’s a badass hidden behind mirrored sunglasses crouching in the open door of a swank vintage Lincoln, and then she’s singing in a fancy dress in front of a chandelier. You can guess which pose feels more natural. She still has to remind herself not to slouch: “I’m just learning how to stand up straight, and I have to remember to posture myself straight on the red carpet,” she says. Or, as she demonstrates, to pull her knees together.

Blige grew up in New York, but her family, like the one in Mudbound, is from the South, and as a child she’d visit her grandmother in the summer at her farm in Georgia. “I always forget to mention that my dad is a Vietnam vet, and my mom and my dad moved from the South to New York for a better life,” she says. “So by the time I was born, he was out of Vietnam, but he wasn’t all the way there. I guess him leaving us at an early age was a part of him wanting to escape a lot of things.”

After her father left, her mother supported the family, working long hours as a nurse, while Mary and an older sister knocked around a housing project in which, Blige once told Oprah, “there was a lot of ‘You better get upstairs’ if you were by yourself because if somebody catch you in the hallway you could end up raped or something.” It was the molestation that gutted her the most, though, she says. To cope, she copped an obstinate attitude in elementary school, telling her principal that she got into trouble “because I don’t take no shit.” It was something that she’d heard her mother say, but, as an adult, she’d eventually realize that her reflexive defiance was becoming corrosive.

The one thing that made her forget about her problems was music. At 7, she won a talent contest, singing Aretha Franklin. Her talent solved her old problems but soon created new ones. She’d recorded herself performing Anita Baker at the mall when she was 17, and her mother’s boyfriend passed on the tape to a co-worker at his Tarrytown car plant who’d been signed with Uptown Records. That landed her a deal with the label, and she began working with Combs — who pushed her hard, she says. “I was never as ambitious as he is. He wanted it so much more. And so because he would push, I would push. I was a dreamer and wanted things, but I never was as ambitious as Puff.”

It’s about this time in our conversation when I realize I’m avoiding sustained eye contact with Blige. There’s something nakedly unprotected about her gaze that’s unsettling. For someone who has been a megacelebrity for as long as she has, Blige seems surprisingly unschooled in the blithe self-salesmanship at which showbiz people excel. Watch clips of her on The Wendy Williams Show, or even as the guest of her obvious admirer Tracee Ellis Ross, subbing for Jimmy Kimmel, and she’s palpably nervous. In person, she’s wary and introverted, occasionally running her manicured nails together as if worried where this conversation might go. “I’m always thinking about, What am I going to say if this person just disrespects me?” she says. “How am I going to handle it? Because back in the day, I didn’t handle it well. I just cursed you out completely, like right out of the gate. But now I think about what I say because then the interview was, ‘Mary cursed me out. She’s a bitch, she’s this, da, da, da.’ ”

When success came — and it came quickly, starting with her debut, What’s the 411?, in 1992 — Blige didn’t know how to handle it, or herself. “I had money, and I had access to all the things that I used to tear my life down,” she says. “I went crazy. I could get any drug, anything, at any moment.” She embarked on a volatile relationship with Cedric “K-Ci” Hailey, of the group Jodeci — they even toured together, with Blige being none too pleased by the attention young women gave him. It didn’t last.

By the early aughts, Blige says she was “very depressed, and I just felt like I wanted to check out.” And then she met Isaacs. They married in 2003, and he became her manager. In a 2011 Behind the Music interview, she credited him with saving her from being a “slumbucket alcoholic” and declared that, thanks to him, she “felt safe for the first time. I had never felt truly loved.”

Fast-forward five years to when that relationship ended in a blaze of infidelity — Blige has called the other woman “my Becky with the good hair” — and financial mismanagement, at least according to the singer’s side of the story. According to a TMZ report last fall, Blige, as part of her divorce negotiations, asserted that she was deeply in debt and owed millions of dollars to the IRS. Isaacs, for his part, has contended that he’s been left traumatized and unemployable.

No doubt to the satisfaction of fans who never quite got onboard with Blige’s sunnier, post-marriage songs, she put all her fury and disillusionment with her former husband into the album she released last year, Strength of a Woman: “You must have lost it, nigga, you won’t get a dime / But all you’re gonna get, too bad, I can’t get back my time / Wasted all this time,” she sings on “Set Me Free,” with the chorus: “There’s a special place in hell for you / You gon’ pay for what you did to me.”

“For me to agree to put something out in the universe like that, I was angry,” Blige admits upon reflection. “And I was just hurt … hurt, hurt, hurt, pissed, pissed, pissed, been scorned, scorned, scorned. Then bitter. When the bitter came, I was like, Oh, no. I’m not going to let this destroy me.” (“I gotta keep myself going, I gotta keep the light going, because you can end up Kurt Cobain–ing out here,” as she told radio personality Angie Martinez in an interview timed to the record release.)

A major takeaway from her divorce is that Mary J. Blige Inc.

must be attended to, she says. “I’m just being straight-up honest. I never wanted to do all this stuff, but after what I’ve been through and all the mess that I’m in … You have to pay those taxes. It’s good to see what you have and what you don’t have — and why are we paying this person $5,000 a week?”

In many ways, these ought to be the best of times for Blige. The morning of her birthday, her star was unveiled on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Combs was there, telling a story about “picking her up from the projects” in his Volkswagen Rabbit and how “we would just dream. Man, we wanted to be somebody … shake up the world.” And they did. Her friend the longtime music executive Jimmy Iovine, who currently works for Apple, was there too, as he’s always been, “whether I was selling records or not,” Blige says. He put her in that Apple Music ad with Kerry Washington and Taraji P. Henson, another friend she met years back at the Grammys; he let her live in his Malibu home after the split with Isaacs left Blige, in her words, “homeless.” He also gave her a talk show on Apple’s streaming service, and in 2016, she interviewed Hillary Clinton, serenading her with Bruce Springsteen’s song about police brutality, “American Skin (41 Shots).”

But now she’s safely ensconced in her high-rise, with her career headed in an unexpectedly exciting direction. In addition to the Best Supporting Actress nomination, she and Raphael Saadiq are up for an Oscar for best song, “Mighty River,” which plays over the closing credits of Mudbound. She’s started a TV-production company, and last fall Fox signed on to develop 8 Count, a drama set in the “cutthroat music/dance world.”

The role of Florence was the real life-changer, she says, opening lots of new options. “Everyone I see, they say, ‘Oh, my God, you were so great. I didn’t know.’ They didn’t know I had whatever they’re seeing in me; they didn’t know I could pull it off. To be quite honest, I didn’t even know I did that good.” She’d moved out to L.A. from New Jersey three years ago to be part of Hollywood, though she misses her family back east. L.A. isn’t quite her thing: “This is very slow. Sometimes you’re just sitting around like, Oh, this is boring,” she notes.

“This is the next chapter,” she says, brightening. “This is why I’m just so humbled and grateful, because I’ve been praying for this and asking for this and it’s here, outside of all this foolishness that’s happening right now.” To wit, it was reported in “Page Six” and elsewhere that she had been ordered to pay her ex $30,000 a month, and he’s asked for more. They’re slated to go to court in March.

But she didn’t want to go into all of that with me. She’s talked enough about it. Maybe quiet is now the way to go for her. After all, Blige built Florence out of silences, something she learned growing up, before she — Mary J. Blige — found her voice. “The neighborhood was really tough,” she remembers. “Everything we saw, we couldn’t say — so that was in me. My mother said whatever she wanted, but my grandmother was just a very reserved woman, very reserved but very powerful. Because you can end up in trouble if you said too much. I mean, Dee saw that. That’s my personality.”

Throughout the film, Blige “just channeled” her grandmother, “the way she stood like this all the time,” she says, placing her hand on her lower back, arm akimbo. And the scene where Florence breaks a chicken’s neck for dinner? “Yeah, that was real. I saw that as a kid. My grandparents, my aunts and them, they was no joke. They killed chickens with their hands, knives.”

Mudbound — which you can stream on Netflix — is a serious film with an at least somewhat hopeful ending. “What I loved about the story is that everybody” —Florence’s family, as well as the white family whose land they worked as sharecroppers — “realized that they were pretty much in the same hole,” she says. “Love is the silver lining of the movie.” But the lessons of mutual respect in the film are hard-won, to say the least, and not shared by everyone. “The Ku Klux Klan just didn’t get the memo,” she observes drolly. But as Rees notes, some forms of racism the film depicts are more subtle and pernicious. Florence realizes that she is viewed, on some essential level, by the white family as a tool that doesn’t exist outside of accommodating their needs. As Rees points out, racism doesn’t always take the form of the KKK. You just have to think that the other people aren’t fully like you.

None of which is news to Blige, of course. I ask her what she learned about herself playing Florence. “I learned that I’m a really powerful woman. I mean, other than just being Mary J. Blige, the superstar, I learned that I’m powerful because I don’t have to say much to be heard.”

Besides, despite her reputation for confessionalism, she slyly tells me she’s always in control of the information. It may seem like she’s baring it all, “but the things that I don’t want people to know, you will never know.”

*This article appears in the February 5, 2018, issue of New York Magazine.