How to Raise a Boy is a weeklong series centered around this urgent question in the era of Parkland, President Trump, and #MeToo.

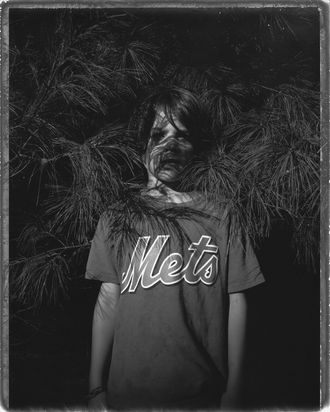

My son Davey began his life in a family that had masculine figures, but no macho ones. His father and teenage half-brothers were what might be called hetero-homo-literary; they liked watching baseball and basketball and pretended to like watching the Super Bowl because they wanted to be part of the cultural conversation. What they loved was music, old movies, and politics. Long before Davey knew who Kobe or LeBron were, he knew Robert Osborne and Tim Russert. He had no interest in playing sports because he came from a family that did not value them. We thought that families who did — the mothers shrieking from the sidelines, and the fathers, oh, the fathers, who’d become successful investment bankers and lawyers and now stood so rigid, studying every facet of their boys’ play, working out their own past conquests and failures through their sons — were, frankly, nuts.

But then Davey’s dad, Peter, got sick and died. Suddenly, my 9-year-old son wanted to play on a baseball team.

I dreaded dipping into that world, about which I knew nothing. But as a now existentially single mother who’d do anything for her bereaved boy, I asked around until I found someone who could tell me how and when to sign him up.

At the first practice, when the coaches told everyone to pair off, no one picked Davey. The boys somehow figured out that he’d never played. Finally, one coach assigned his kid to toss with mine. After about five minutes, the boy sneered: “You suck. I’m gonna throw with a kid who can actually catch.”

Davey looked forlorn. My thoughts, in some random order, were, I hate that kid, I hate this, this doesn’t matter, this is not who we are, we are out of here.

Except that Davey insisted on going to the second practice.

Since then, my ideas about how to raise him have evolved. Or devolved. In the beginning, I was obsessed with creating my idea of the perfect male. If I brought him up to be in touch with his grief and more generally his emotions, to be politically liberal but not knee-jerk, to be an effortlessly straight-A student, to be talented on the piano, familiar with the American Songbook, the Stones versus the Beatles, I would have undone the cataclysm of the death of his father. I’d have raised him to be like his father.

What would Peter have done? There was no way he’d have done what Davey and I began doing: having catches in the street, hitting balls off a tee in the yard, finding a batting coach to work with him. I sat on dented aluminum stands in worn-out fields for hours and hours, a stranger in a strange land of dads and male athletic rituals. I watched the fathers, grimacing when their boys made errors but whooping with real joy when they did something well. I noticed that the boys beamed when their fathers were pleased, yet hardly acknowledged their mothers. There was a crustiness developing among them. They roared for one another. They cursed, when they could get away with it. They began butt-patting and crotch-adjusting. They reveled in the dirt-caked Gatorades and rutted infield and the team dinners. Many of the boys could’ve left the team to play elsewhere, but four years later, most of them are still on it. It’s their country of men.

I now know that my kid sensed what he needed. As his father was growing weaker, Davey needed to feel strong. As he was losing Peter, Davey determinedly pursued a path that Peter never could. Tough jocks were what was required, not a mother’s smoothing and curating, and the jocks came through for him in ways grand and subtle. One shockingly pleasing day, Davey hit a walk-off grand slam. This triggered a boy bacchanal as his teammates mobbed him at home plate. One of his coaches, phoning in from a family vacation, cried.

When Davey was hit in the face by a pitch a year and a half ago — blood gurgling from the places where his teeth had been knocked loose — I was restrained by other parents from running onto the field. After what seemed an eternity, the coaches brought him to me in the stands. They were concerned and gruff, fatherly and nonchalant. Davey, his uniform stained in blood, looked happy.

*A version of this article appears in the March 5, 2018 issue of New York Magazine.