The Pigpen-style swirl of crime around the president who nominated Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court is extraordinary. Still, there is one very standard aspect of the Kavanaugh nomination: the obfuscating code words around abortion. The judicial nominees of Republican presidents in particular have historically said as little as possible about abortion in their hearings, the better not to awaken a public that to this day is overwhelmingly supportive of Roe v. Wade. “Do I have this day an opinion, a personal opinion on the outcome in Roe v. Wade?… [M]y answer to you is that I do not,” Clarence Thomas solemnly declared in his own hearing. Nine months later, as a justice, he joined an opinion stating, “Roe was plainly wrong.”

Candidate Donald Trump broke from the euphemisms to claim that Roe’s demise “will happen automatically in my opinion because I’m putting pro-life justices on the Court.” And when Kavanaugh’s name was first floated to replace retired Justice Anthony Kennedy, conservative insiders publicly reassured their own nervous ranks about his anti-abortion bona fides. “On the vital issues of protecting religious liberty and enforcing restrictions on abortion, no court-of-appeals judge in the nation has a stronger, more consistent record than Judge Brett Kavanaugh,” wrote one former clerk, while a conservative attorney offered, “There is no reason to conclude that Kavanaugh would support Roe and Casey when presented with the question as a Supreme Court justice.” The moment Trump actually named Kavanaugh, however, the gaslighting of abortion supporters began: People who dared worry about the future of the procedure were “scaremongers” consumed by “hysteria” — after all, Kavanaugh was such a stand-up guy he’d chosen female clerks! People, it’s all on the internet; we can read.

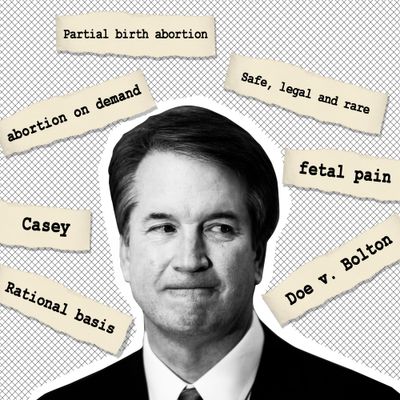

Nonetheless, Kavanaugh’s hearings will be full of doublespeak. For help reading between the lines, consult the below.

“Abortion on demand.”

Thrown around by the right — including Kavanaugh, who tellingly used it three times in his one major abortion opinion — to denote women capriciously making decisions for themselves.

“Balls and strikes.”

By his own account, Brett Kavanaugh racked up tens of thousands of dollars of debt on baseball tickets, so perhaps he’ll revert to Chief Justice John Roberts’s aw-shucks mantra in his 2005 confirmation hearings: “I will remember that it’s my job to call balls and strikes and not to pitch or bat.” In other words, he promised to uphold the law and the Constitution, not impose policy preferences, like making abortion illegal. Of course, cases usually get to the Supreme Court because other judges have reasonably disagreed on what the law or Constitution means.

“Between a woman and her doctor” and “safe, legal, and rare.”

Some Democrats still use these vintage pro-choice talking points, but they grate on a new generation of abortion rights activists. “Between a woman …” implicitly defers to a white-coated professional over a pregnant person’s reproductive autonomy and doesn’t acknowledge that trans people have abortions. “Safe and legal” still has lots of fans on the left, but “rare,” as Tracy Weitz put it, “separates ‘good’ abortions from ‘bad’ abortions.’” In 2012, Democrats took the Clintonian slogan out of their platform.

Casey (or Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey).

This unloved legal compromise, decided by the Supreme Court in 1992, declined to overturn Roe but said states could erect all kinds of roadblocks to prevent women from exercising that right — as long as the obstacles don’t present a so-called “undue burden.” The legal haggling ever since has been over exactly which burdens are undue. You can thank retiring Justice Anthony Kennedy for this unwieldy creation that at least kept abortion legal for the past 25 years. And then you can thank him for making way for the man who may undo that.

“The democratic process” or “It should go to the states.”

This is what you’re likely to hear from Republicans, and what’s not to like about some good old-fashioned democracy? Well, previously in the democratic process and states’ rights: bans on interracial marriage and other Jim Crow–era restrictions. “The democratic process” would likely mean the loss of abortion access in 22 states, but regardless, these arguments purporting to be about process are really about achieving certain outcomes. Congressional Republicans weren’t exactly respecting states’ rights when they introduced federal personhood bills, prohibitions on race- and sex-selective abortion, or legislation to forbid abortion at 20 weeks or when the fetal heartbeat can be detected. In fact, the GOP platform includes support for a human life amendment that would outlaw all abortion everywhere.

“Dismemberment abortion,” “partial-birth abortion,” and “fetal pain.”

These are political, not medical, concepts cooked up by the anti-abortion movement to refocus the debate on the fetus and on potentially uncomfortable details. In 1995, when the National Right to Life Committee heard about a doctor performing abortions through intact dilation and extraction, they named it “partial-birth abortion” to “foster a growing opposition to abortion,” and the Supreme Court signed off on banning it. The Court has yet to weigh in on laws passed in 17 states blocking abortion after about 20 weeks on the medically unproven theory that the fetus feels pain at that time, or on prohibitions against “dismemberment abortion” —another concocted term for a common and safe abortion method — that was passed in nine states.

Doe v. Bolton (1973).

You don’t hear much about this lesser-known companion case to Roe v. Wade, decided at the same time, but it’s GOP code for “women having abortions willy-nilly.” In this case, brought on behalf of a Georgia woman, seven justices ruled that abortion could be banned at viability as long as there was an exception for a woman’s health, defined broadly by a physician as “all factors — physical, emotional, psychological, familial, and the woman’s age — relevant to the well-being of the patient.” Doe v. Bolton is why Paul Ryan once sneered, “The health exception is a loophole wide enough to drive a Mack truck through it,” and John McCain, when debating the issue, put derisive air quotes around the word “health.”

Dred Scott v. Sanford (1857) and Plessy v. Ferguson (1896).

These irrefutably wrong Supreme Court decisions upholding slavery and segregation are evoked by conservatives in the abortion debate to (1) compare abortion to slavery, and (2) point out that some Supreme Court precedents are actually bad. When George W. Bush brought up Dred Scott in the 2004 presidential debate, one Evangelical leader called it “a poignant moment, a very special gourmet filet mignon dinner.”

Garza v. Hargan or Garza v. Azar (2017).

The rare abortion case on which Kavanaugh has ruled. The Trump administration unsuccessfully tried to bar a raped migrant teenager from leaving detention to have an abortion, even though she’d jumped through all the legal hoops. Some conservatives protested that Kavanaugh didn’t go far enough by not joining another dissent that claimed that legally, an undocumented immigrant is not a person. Kavanaugh’s own dissent would have run out the clock by looking for a sponsor, a process that had already delayed the young woman’s abortion by seven weeks and threatened to push her pregnancy past the legal limit. The biggest tell of all: Kavanaugh deferred to rulings keeping abortion legal but wrote, “As a lower court, our job is to follow the law as it is, not as we might wish it to be.” On the Supreme Court, on the other hand …

“Even Ruth Bader Ginsburg hates Roe v. Wade” and “the Ginsburg rule.”

Yes, Ginsburg has often critiqued Roe, but that’s because she preferred a different strategy (incrementally striking down abortion bans rather than all at once); legal basis (women’s equal citizenship rather than right to privacy); language (maybe a tiny bit less patronizing to women and deferential to doctors); and test case (specifically her own client, a nurse the military was trying to force to abort). So what? It doesn’t make her any less an unbending supporter of reproductive freedom, and it’s irrelevant because Casey, which she likes a bit better, is the standard we now have. As for the so-called Ginsburg rule Senate Republicans invoke to say Kavanaugh doesn’t have to say shit about shit: While Ginsburg did say in her 1993 hearing that she didn’t want to speculate on future cases, this is what she also said in those same hearings: “[Abortion] is something central to a woman’s life, to her dignity. It’s a decision that she must make for herself. And when government controls that decision for her, she’s being treated as less than a fully adult human responsible for her own choices.” By all means, let’s have Kavanaugh follow the Ginsburg rule.

Griswold v. Connecticut (1965).

This opinion struck down a ban on contraception for violating a “right to marital privacy,” forming some of the basis for Roe. Asking about it has been used as a proxy for asking about Roe; those who express reservations about Griswold probably feel the same about Roe, in other words.

“Original public meaning,” and “originalism.”

This is the conservative dictum that judges should stick to the framers’ intentions, popularized by the late Justice Antonin Scalia. Taken to its strictest conclusion, originalism could make it legal to discriminate against women and LGBT people, legalize segregation — and of course ban abortion. Some liberals argue that the framers intentionally used broad language to encourage interpretation over time.

“Rational basis.”

While Casey said states could only restrict abortion as long as it didn’t put an “undue burden” on a woman’s access, “rational basis” would be an even lower bar, one that the conservative Fifth Circuit tried to slip through in Whole Woman’s Health only to be slapped down by the Supreme Court. Under rational basis, almost any restriction on abortion would be allowed to stand without much scrutiny — say, requiring all medical equipment to be gold-plated — as long as it sounded reasonable.

Roe v. Wade (1973).

Only two justices dissented from the opinion that struck down all state abortion bans, and one was Justice William Rehnquist, who in 2017 Brett Kavanaugh called his “first judicial hero.”

“Settled law” or “precedent” or “stare decisis.”

When Kavanaugh told Maine senator Susan Collins that Roe is “settled law,” she was satisfied that he wouldn’t go after the fundamental right to abortion. But mouthing the right words about how the Court is supposed to avoid sudden moves doesn’t mean long-standing decisions can’t be toppled. Chief Justice John Roberts, who called Roe “settled as a precedent of the court,” has never voted against a restriction on abortion. Plus, he’s voted to strike down plenty of long-standing precedents with regard to voting rights, union rules, and money in politics.

Stenberg v. Carhart (2000) and Gonzales v. Carhart (2007).

With the help of Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, the court struck down Nebraska’s “partial-birth abortion” law because it had no exception for the health of the woman. But when she retired and was replaced by Justice Samuel Alito, the court waved through a federal version. So much for precedent.

Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt (2016).

In the Court’s last big abortion case, Justice Anthony Kennedy voted with the four Democratic appointees in ruling that states had to have a really good reason for regulating abortion clinics out of business. If the Court would overturn just this single, very recent so-called precedent, the last clinic in Mississippi would be forced to shut down, and quite possibly nearly three-quarters of the clinics in Texas — to name just two states where abortion access would be severely curtailed.