More than 300 people gathered at the Brooklyn Museum last night to listen to 87-year-old Faith Ringgold speak about her extraordinary career and activism, which included fighting for major New York City museums to feature work by black artists in the 1960s. Two of her artworks appear in the Brooklyn Museum’s recently opened retrospective, “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, which features black artists who explored themes of race, identity, and activism from the years 1963 to 1983.

The sold-out event began with deafening applause and a standing ovation when Ringgold took the stage with her daughter, the art historian and critic Michele Wallace. “I became an artist because I wanted to tell my story as a black woman in America,” Ringgold began. “It was the height of the civil-rights movement, and I wanted my art to be a witness to the changes that were taking place.”

Ringgold was born in 1930 and grew up in Harlem. In 1955, after marrying her first husband and having two children, Ringgold attended the City College of New York to study art and earned both her bachelor and master’s degrees. She soon became a vocal civil-rights activist, and created protest posters for the Black Panthers. She also organized her own protests outside major New York City museums that featured no work by black artists.

“Different people were complaining and I remember saying, ‘Why don’t we just demonstrate?’” she recalled. “The Whitney was the first.” She protested at the Whitney in 1968 and 1970. After the second demonstration, sculptors Betye Saar and Barbara Chase-Riboud were included in the museum’s sculpture biennial, as the first black female artists to be exhibited at the Whitney.

Ringgold’s daughter, Wallace, added that she and her mother were among the first to protest the Met’s controversial 1969 “Harlem on My Mind” photography exhibit, which featured no black artists. After more people joined the protests, the Met’s director apologized, and the museum began to include work by black artists in its collection. Today, several works by Ringgold are on permanent display at both the Met and the Whitney.

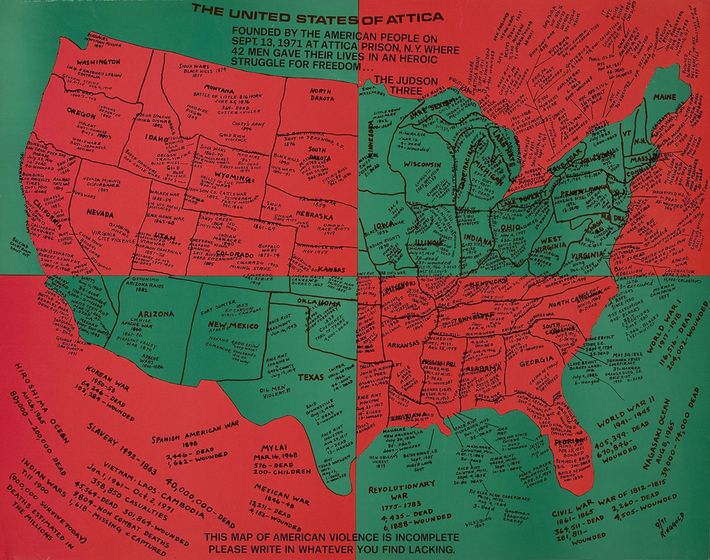

Ringgold now creates illustrated children’s books from her studio in New Jersey. In “Soul of a Nation” at the Brooklyn Museum, her works on display are The Flag is Bleeding (1967), which she painted to represent oppression and violence against black people in America; and the United States of Attica (1972), a map of violence in the U.S. as a response to the Attica Prison riot in 1971. Learn more about the exhibit here.