I’ve been on this planet for 33 years, and I have had more than that many jobs. Most recently, I worked on the upcoming season of The New Yorker Festival.

When you have many jobs, you get asked to do many strange things. I’ve been asked to drive 30 minutes to fetch a particular flavor of “concrete” — a concrete is a type of ice-cream treat, sort of like a McFlurry, but not from McDonald’s. An off-brand McFlurry. I’ve been asked to organize closets of shoes, to write speeches, to run events, to fill gift bags, to count nuts and bolts, to purchase yogurt, and to sing on cue.

When you need a paycheck, it’s hard to say no. That’s part of why, until recently, I never have. It’s easier to go with the flow than to beat back against the waves, raise your fists in the air, and lose the work that you so desperately need. Especially as a woman: Women get gold stars for flexibility. Gold stars for being game. “I know this isn’t a part of your job, but …” is a preamble we’ve heard before. You can tackle the task at hand, or you can Bartleby the Scrivener your way straight to unemployment.

The only time I have ever said no to a task at work was in my freelance position at The New Yorker this past year. For two seasons, I wrote, edited, and footnoted the talent bios for The New Yorker Festival. It is a task that one friend described as the literary equivalent of dishwashing. Not quite — I’ve done actual dishwashing, at shops, both coffee and ice cream — but I see the point.

All of the content on The New Yorker’s website must be original, and factually correct, and so every bio for the festival is written in-house. And by in-house, I mean by me, on my laptop, at my desk. It can be tedious work, but the tedium gives way to an interesting tango between a person’s vision of themselves and a factual expression of a career’s content. The challenge is to report achievements without editorializing, with an eye for what might feel important at the moment of the event, while tuning in to irrelevant or erroneous material. Each bio must be phrased differently than every other bio available online or in print. Each bio is cited, delivered to the copyediting department, and then to the fact-checking department. At the midway point in the process, each bio is transported home to its protagonist, and is met with either humility, corrections, or a combination of the two. The finished product is a glossy little gem, a box of accumulated achievements, arranged and itemized and approved. Even the word itself — “bio” — feels like something smooth and sorted.

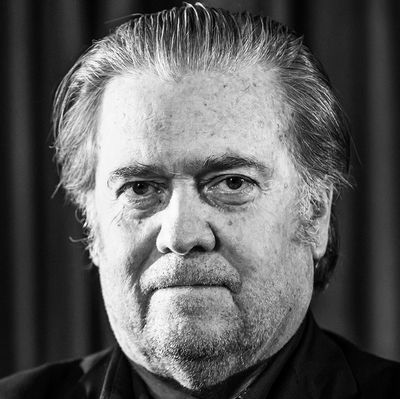

I have written nearly 300 of these bios over the course of two New Yorker Festivals. Last week, I was asked to compose one final gem box. This time: for Steve Bannon. I declined.

A bygone employer would often tell me to make restaurant reservations. Then, on the day of said lunch or dinner, she would request that I cancel the reservation. The pattern continued as such, and I started to wonder: If a reservation is canceled in the city and no one is there to hear it, do I even exist? And so, with great caution, I stopped making the reservations in the first place, knowing that eventually, the un-made date would unmake itself. In this way, I could extract myself from the existential dilemma of doing something while really doing nothing at all.

When I was asked to write Steve Bannon’s bio, doing nothing was not an option. Or rather, I decided to do something by doing nothing. Or rather, even if your job means nothing to most people, it still means something to you. I took pride in the little houses that I built for the stories of people’s careers. I did not want to build a little house for Steve Bannon’s career, a career that does not deserve a platform or an honorarium. Platforms are a privilege, not a right. My own platform is bigger than some, quite small compared to others. But I do have the tools to build a little house, and the ability to put those tools away.

I’m not naïve, and I knew that one way or another, Bannon would eventually have his bio. But if I could halt progress for even a moment by sticking the gears of the process in place, by making things just a tiny bit difficult, I could turn my literary dishwashing into literary dish-smashing. There was no way for me to write a neutral, 90-word list of credentials for someone who, I feel, is only credentialed in his ability to fuel hate. There was no way for me to spin something dangerous into something benign, a tally of accolades, smooth and sorted.

I have never said no to a task at work, because when there is work to be accomplished, a good job can always be done. You can never demean yourself by doing a good job, unless that job demeans your community, the people around you, the people far from you, their lives, your life.

Here’s the thing that I didn’t realize about the restaurant reservations before I stopped making them: The retraction of the reservation was not an equal and opposite reaction to the booking. The two actions did not cancel each other out, because there was always residual matter at play: the conversation with the person at the restaurant, on the other end of the line. The byproduct was human interaction. By not making the reservations at all, I removed this relationship from the equation.

Every job, no matter how small, leaves a trace. Sometimes it’s benign; a chat on the phone with a stranger. Sometimes it’s malignant. On Monday, I watched as the Steve Bannon event was done and undone, and I considered what was left behind.

When you think of the word “bio,” think accolades, think awards. Think, at its highest standard, a summary of a life. I could list the strange things that I have done in my life. A bio of odd jobs. But the task of normalizing Steve Bannon will not be included. You can fact-check it.

Hilary Leichter’s first novel, Temporary, will be published by Emily Books/Coffee House Press next year.