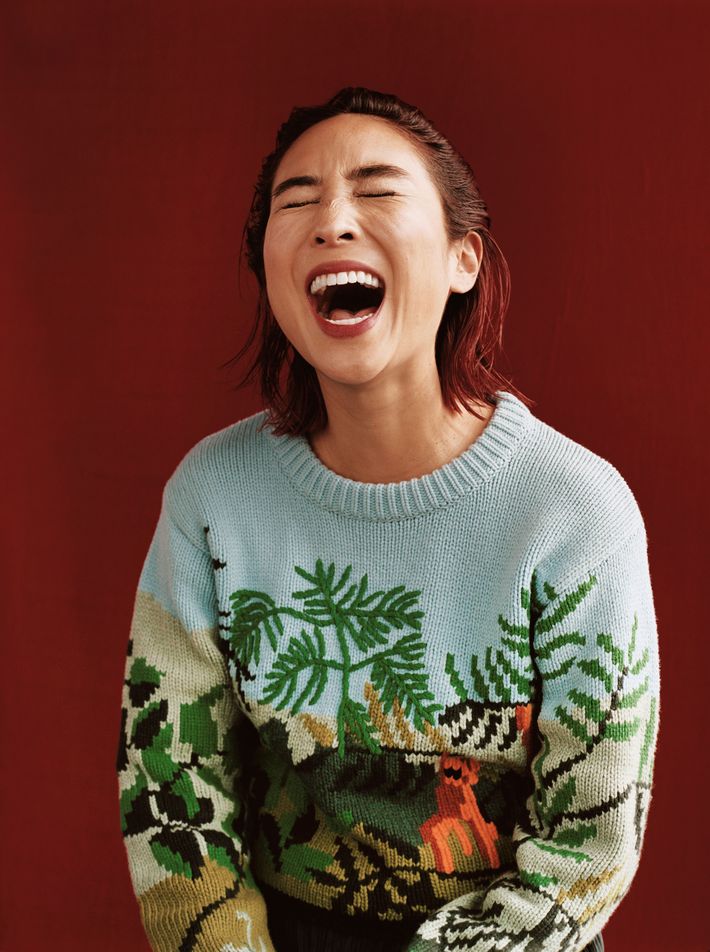

At this rate, Greta Lee has about seven good years left with her teeth.

“I have my SoCal vibe of like, ‘Yeah, really cool, it’s fine,’” the 35-year-old L.A. native tells me over lunch at Soho’s Blue Ribbon Sushi, her smile currently intact beneath a beanie and a blunt, electric magenta bob. At night, though, the actress grinds her teeth, the pressure pulverizing the enamel, and she’s been told that if she doesn’t want a mouth full of “little dusty nubs” by 2025, she needs to find a way to relax. Her dentist suggested meditation.

But Lee hasn’t had a lot of spare time to meditate. In the past several years, she’s made a name for herself stealing scenes as a series of bratty, entitled, but endearing weirdos — Soojin, the ditzy gallery girl on Girls who gets fired by a naked Jorma Taccone after she takes a bite of his rosewater ice cream; Homeless Heidi on High Maintenance, who scams Brooklyn yuppies into letting her move in with them and buying her fancy food, drinks, weed; a host of absurd, neurotic friends on Inside Amy Schumer.

In less skilled hands, these characters could easily wilt into limp, forgettable foils. But with a combination of warm, protective empathy, and wit like an obsidian blade, Lee shapes their brattiness into something at once lethal and captivating. (“It is amazing to me how many people have told me that these ‘crazy women’ remind them so much of women they know,” she tells me, “And I’m like, ‘I’m so sorry.’”) Onscreen, Lee thrums with energy, easily holding her own against, and occasionally eclipsing comedic powerhouses like Amy Schumer, Amy Poehler, and Hannibal Buress.

Now, she and Jason Kim — formerly a writer for Girls and currently a producer on the hitman comedy Barry — are writing and developing KTown for HBO, a dark comedy about the Kang family, kingpins in L.A.’s Koreatown. Lee is slated to play Yumi Kang, the Brentwood Barbie who returns home and reconnects with her “embarrassing” Korean roots. If the series gets picked up, it will be the first cable show ever centered on Asian-Americans. And that’s so exciting, Lee says, but it’s confusing, and painful, too. Why hasn’t this happened before? Why did it take so long? Why are they the first? Plus, she and her husband still need to construct the very specific Halloween costume her 2-year-old has in mind. And, oh, also, she’s pregnant.

“It’s like, yeah, let me just find that time to meditate and I’ll get back to you.”

As a child, Lee’s high internal voltage wasn’t always considered an asset. Everyone in her family, she says, is either a doctor or an artist. Her mother is a trained concert pianist, who studied at the prestigious Ewha Womans University in Seoul. She and Lee’s father, a physician, married in Seoul, and moved to Los Angeles in the early 1980s, shortly before Lee was born. They named her after Greta Garbo, the 1930s Swedish-American film star, in honor of Lee’s paternal grandfather, who worked as a billboard painter at an American Army base during the Korean war, painting huge advertisements for the classic movies that would be screened for the American soldiers, which is how he fell in love with film and was introduced to stars like Garbo.

When Lee was a baby, the young family set off across the country, trying to find a hospital that would hire her father, an immigrant with a Korean medical degree who didn’t speak English. (“I hear this story, and I’m like, ‘Oh my God,’” Lee says.) He eventually found work on the East Coast, the family settling briefly in Springfield, Massachusetts, where Lee’s sister was born, and then Canarsie, New Jersey, where her brother was born, before returning and putting down roots in L.A.

“Growing up in a somewhat traditional Korean household, having that energy wasn’t seen as the best thing,” Lee explains. She was supposed to be ladylike, and she wasn’t. As a kid, she was goofy, a ham who sang Mariah Carey’s “Hero” over back up tapes until her voice gave out, who wanted to be a pop star and the president at the same time, and who, in high school, “really needed to try smoking cigarettes and really wanted to join an Asian gang.” She wanted to take up space, to make noise, to assert herself in a world where she didn’t see anyone who looked like her or her family on TV or in magazines.

“It sounds extreme,” she says quietly, poking at a piece of tuna sashimi. “But when you have no sort of representation, when you’re completely absent from media or from everything you’re consuming, no matter how strong your support system is, subconsciously, the subliminal message is, ‘You are defective.’ And I’m just beginning to understand the scope of how damaging that is to people and to myself.” Her words are careful, precise, molded, she says, by years of therapy.

To help channel her relentless energy, Lee’s parents enrolled her in classical singing lessons, shuttling her to competitions all around California. It wasn’t until years later, when she was studying theater at Northwestern that she first understood she could be funny. She didn’t grow up worshipping Saturday Night Live like so many of her comedy peers. She doesn’t think she even knew what it was when she was a kid, and even if she had, she probably wouldn’t have watched it. “Nothing in my childhood or the way my parents raised us ever would have allowed me to think that comedy was cool,” she says. She fell into sketch comedy, and when she really started making people laugh, something clicked. It felt like people understood her.

The process of getting those laughs, however, was sometimes complicated. It feels like flying a little bit, Lee tells me, when you step into the right part in the right situation. Before playing Homeless Heidi and Soojin though, she’d only gotten that feeling when she was using a big, broad Asian accent. “That was so confusing, because there was comedy in that, and I was trying to figure out what that was, but it felt like a cheap laugh. I didn’t feel great about it.” And yet, this device opened doors for her: While auditioning for the musical “The Life” at Northwestern, she did what she describes as a “horrible Vietnamese accent,” and it killed. The play’s director loved it so much that they wrote a whole new role for her. “People loved it, but how crazy!” Lee exclaims. “I couldn’t just play one of the written roles? But they wanted me to do this.”

After graduating in 2005, she and her Jack Russell-Poodle mix, Batman, packed up and moved to New York. Lee did one episode of Law and Order: SVU — playing the brainy college roommate of a girl who had an incestuous relationship with her politician father — and then almost immediately started working on Broadway, first in The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee, and then La Bete. In 2012, she was playing Amanda in a Lincoln Center production of 4,000 Miles, where she caught the eye of Lena Dunham. Dunham was so charmed by her performance, that she wrote the role of Soojin for her in Girls. Then Amy Schumer cast Lee in her sketch show, and she worked with Amy Poehler and Tina Fey in Sisters (another role where she would have to put on a heavy Asian accent). She’s grateful for those women, but she’s also frustrated that she needed them to get this far.

“I feel uncomfortable saying this, but they’re all white women, right?” she says, watching my face. “I’m still finding myself in these situations where I see that we need backups. There’s only so much I can do.”

“We need people to be advocates,” she goes on. “Viola Davis talked about this with her Emmy’s speech: ‘I’m only as good as the opportunities I’m given.’ And that’s so loaded. Because we’re beholden to people, and I want to make my own opportunities, and I want to be empowered and in control. But we’re not quite set up yet.”

Crazy Rich Asians changed things, she says. A little bit. This summer’s biggest rom-com was Hollywood’s first film with an all-Asian cast since The Joy Luck Club in 1993, and it shattered box office records, becoming the top-grossing romantic comedy in ten years. Lee’s trip to L.A. with Jason Kim to pitch their show that same summer was one of the weirdest experiences of her life. After years of being told there was no market for the stories of Asian-Americans, studios were now overwhelmingly eager about KTown. “There were so many people that were like, ‘YES PLEASE.’” The experience was so foreign that Kim, she says — the producer would be okay with her telling me this, she thinks — cried during pitch meetings.

Initially, Lee and Kim hadn’t really set out to write a show about Korean-Americans together. In a way, they tried really hard not to. The pair just wanted to write something funny. But as they worked, they spent so much time talking about their families (Kim was born in Korea, and he and his family moved to the States when he was a child) that at a certain point it became almost harder to not make the show about their upbringings — though, she stresses, it’s still a comedic show before it is a show about Korean-Americans. And it isn’t directly about their families, exactly. The Kangs of KTown skirt the edges of the law, because those are the kinds of stories Lee says resonated with her and Kim the most: “It’s this question of, when it’s a fight for your life, what are you willing to do for your family?”

She cites as inspiration the story of Young Lee, the co-founder of the wildly popular frozen yogurt chain Pinkberry, who was sentenced to seven years in jail in 2014 for beating a homeless man in L.A. with a tire iron. And Forever 21 — which she’s mentioning “in a nonjudgmental way” (she went to high school with the founders’ kids) — doesn’t exactly have the best reputation. The clothing chain, founded by Korean-Americans Do Won Chang and his wife, Jin Sook Chang, has faced a number of scandals, lawsuits, and copyright infringement claims. In 2012, a nonprofit found that Forever 21’s Long Pearl Flower Necklace, contained high levels of hazardous chemicals. “I was like, isn’t it almost easier for them NOT to make them from that?” Lee deadpans.

The choice to make the Kangs criminals has been met with some anxiety from people concerned about the impact of an Asian-American Sopranos. Lee understands where they’re coming from. “This is the result of being so underrepresented,” she explains. “To have a chance to represent a group, of course people are going to feel protective. Like, don’t make us look bad!” But overall, the response has been overwhelmingly positive. So positive, in fact, that someone has already shown up at HBO’s offices asking to audition for the show, which, at the time of our interview, Lee and Kim are still in the process of writing. This is why, she says, even as an actor-for-hire who has been a part of multiple failed pilots, she feels like she can talk about the show before it’s made. Something feels different this time.

One cold, gray October morning a few days after our lunch, I’m standing at the top of the stairs in front of Lee’s Brooklyn home, trying to figure out if I rang the right doorbell when I hear a door open and close below me. Two voices float up — one deep and mollifying, the other small and aggrieved. I peer over the railing and see Lee’s husband, actor and writer Russ Armstrong, whom she met at Northwestern, and her son, preschooler Apollo. In one hand, Armstrong is carrying a small, lunchbox-sized backpack; in the other, a plastic lantern painted melon-green. Armstrong spots me lurking and ushers me inside, while Apollo eyes me skeptically, eager to get to his preschool’s Halloween parade.

“Come upstairs and you’re gonna see just … this is it,” Lee says, guiding me into her kitchen. As we discuss Apollo’s costume choice — when he told them he wanted to be a “Honeyboo” melon weeks ago, they kept thinking he would change his mind, but he remained resolute — Lee scurries around, stowing away Apollo’s high chair, wiping up spills from his breakfast (oatmeal), making us espressos, and navigating around the now-elderly Batman, who is graying and a little blind.

Motherhood has clarified a lot for Lee, she says when we’re settled around her large granite island, which is still covered in newspaper and melon-green paint. “I’m tired, and I have to wake up with a kid who’s 2 and who doesn’t care at all about what part I didn’t get or what part isn’t lifting up my racial community enough,” she explains. “He’s like, ‘Where’s my oatmeal?’”

When I call Lee again a few weeks later, she’s well into her second trimester and says she’s struggling, as she did when she was pregnant with Apollo, with the cognitive dissonance of pregnancy. “It’s so hard to reconcile how weird it is to be a mom, and to feel empowered to bring to life a human, while simultaneously being told pretty explicitly by other forces in the world that women are worthless, if not less than.”

After she had Apollo, she says she tried to “get back out there” again (“Whatever that means”) as quickly as possible, squeezing herself into medical grade Spanx weeks after her C-section to go to a fashion show. But with this pregnancy she says she’s trying, trying to take it easy and relax a little more, which goes completely against her nature. These days, she needs to really want to do a role to take it on.

Which isn’t to say every role has to be perfect. There are certain questions Lee finds herself asking whenever she’s offered a part: What is she sacrificing just to be at the table? If it hasn’t been completely on her terms, does she just not show up? And even if the role is flat as a board, what would it mean for people to see someone who looks like her taking this on and making it her own? What would it mean for her son to have the sort of representation that she didn’t have growing up?

“Having my son is like holding a mirror that I have to look at every day. The things that I was able to ignore or reject as a kid, like my roots, my identity, it becomes really hard to do that when you have someone looking back at you.”

Already, in mere anticipation of KTown, more eyes than ever are on Lee. She’s worried about people looking to her as a role model, or as some kind of representative of Asian-Americans. A part of her doesn’t really want to take that on because, as she puts it, “there are things about me that I would never endorse.”

“It makes me really anxious. Being seen. Which sounds nuts, because I’m an actor,” Lee says, scraping off a last bit of oatmeal off the island. “But there are things about my family … It’s not a perfect story of immigrants moving to a wonderful, welcoming place where every step of the way has been magic.”

Her husband’s been reading books on radical transparency, and the concept of that openness scares her, but who knows? Maybe all of this — the show and motherhood and pregnancy and the pressure of representing the underrepresented and the teeth grinding — is its own exhausting and continual kind of meditation.

“I’m just so tired that it’s kind of effective in making me feel like, you know what—,” she shrugs. “This is what I’ve got.”