Now that having a name stitched on the ass of your jeans — be it Calvin or Tommy or whomsoever — has become a matter of course, it’s easy to forget the leap Gloria Vanderbilt took in the ’70s when she appliquéd her own. Who would have imagined it? Descended of Morgans and Vanderbilts, some of the richest families of the Gilded Age, she had one of the most august names in America. She had survived tabloid coverage of a custody battle between her mother and aunt with her dignity intact, entertained high society, and still she descended to enter the garment trade. And yet, at that febrile moment in style, with American sportswear on the rise but the major names of the ’80s (Calvin, Donna, et al.) not yet on firm footing, the gamble paid off. When the decade ended, there atop the fashion pyramid was Gloria Vanderbilt, designer denim magnate.

In his year-by-year history of American style for New York at the end of the decade, the great fashion writer John Duka gave Vanderbilt the last word. 1979 has been the “apotheosis of Gloria Vanderbilt, jeans and jogging uniforms,” he wrote, and went on:

“It should, by now, be as plain as the Porsche jacket on your back that by decade-end the sixties goal of dressing the way you wanted had been more or less achieved. It was people that made fashion. Or movies. Or disco. Or L. L. Bean. Or Adidas. Or Levi-Strauss. And Seventh Avenue tried desperately to stay in touch. As if overnight, the monolithic structure of the fashion industry had evaporated, leaving Gloria Vanderbilt smiling more broadly than ever at the top.”

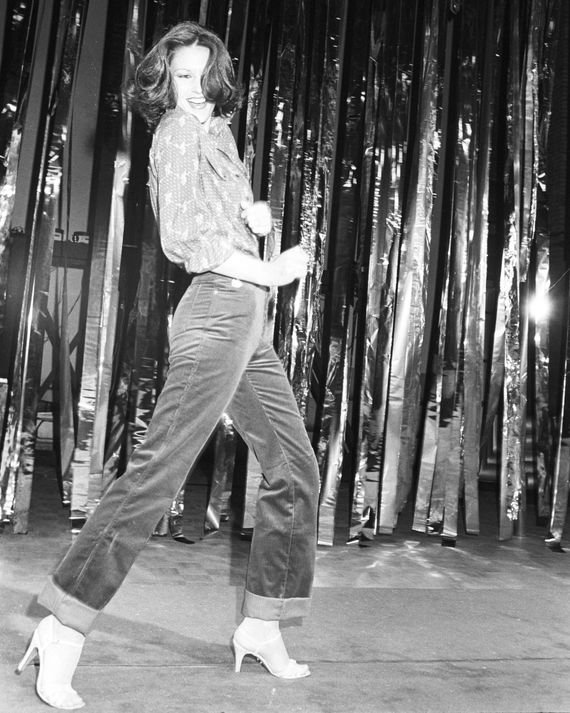

It was people who made fashion: not the dictates of a handful of companies or haughty couturiers. The decade had seen the wrap dress of Diane von Furstenberg and the trouser drag of Annie Hall, individuals who didn’t wait for retail executives to dictate how they should look or feel or act. Suddenly Vanderbilt, who had been photographed in couture in the pages of Vogue and Bazaar, went from mannequin to mastermind. It was good business to be one of those who people who made fashion: At the height of her empire, Gloria Vanderbilt jeans were reportedly bringing $100 million a year, and Vanderbilt was bringing in an income of her own, uninherited.

The brand still operates today, but Vanderbilt herself moved on. She spent her last years painting and writing a late-career erotic novel.

As one of the last swans of an earlier, tonier American aristocracy, she will be remembered for her long, and many chaptered-life, one that spans much of the 20th century. (She stayed keyed in to its changes to the end; she loved Instagram.) It is only one moment, but what a moment it was, when she appeared on the airwaves (well, she or Debbie Harry), to extol the virtues of jeans that “give you the hug but not the squeeze.” There she was, the society beauty whose riches and trials had been making newspaper headlines since before she was reading age, gamely pushing her “stretch denims.”

“They feel simply wonderful on, and they fit…” she began, and a model finished for her: “Like the skin on a grape!”