“I Think About This a Lot” is a series dedicated to private memes: images, videos, and other random trivia we are doomed to play forever on loop in our minds.

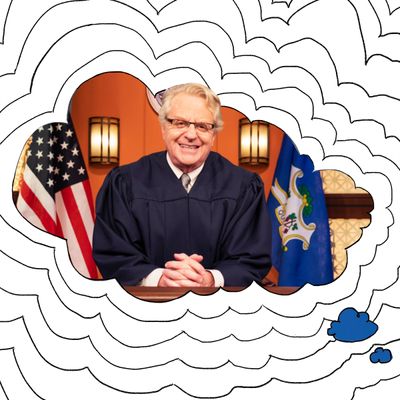

This year marks the final season of The Jerry Springer Show, a dubious pillar of the television landscape for the past 30 years. Starting this fall, Springer will star in a new program, Judge Jerry, on which he will serve as a judge in small-claims court. Clad in a black jurist’s robe before a fist-pumping studio audience, Springer will “render a verdict with a fair yet firm hand and always leave litigants with a dose of classic Jerry Springer wisdom,” according to a press release from NBCUniversal. The launch of this new persona has me thinking a lot about the last time Jerry Springer reinvented himself — and who he might have been if he had not.

As a 2004 episode of “This American Life” poignantly chronicled, the original version of Jerry Springer was someone quite different from the figure we have come to know and love/abhor. At the time the episode aired, Springer was considering what some might not have known was a reentry into politics with a bid for an Ohio Senate seat. By then, Springer’s reputation as a sensational TV host had made him one of the more laughable potential candidates in American politics. But as “This American Life” deftly illuminated, the prospect of Springer’s political career was less absurd than those who were unfamiliar with his previous foray into government might think — or was absurd in ways that were not completely straightforward.

Springer began his career in 1971 as a promising and beloved Cincinnati City Councilman. His politics were progressive — he was anti–Vietnam War, pro–civil rights, and viewed himself as an advocate for the marginalized. His political talents were enormous, according to those who knew him at the time; he drew regular comparisons with Bobby Kennedy. One of the central features of Springer’s political charisma was his ability to talk to absolutely anyone about absolutely anything: He’d regularly discuss his opposition to the war in VFW halls. He would one day deploy this quality in a much-different context.

In 1974, Springer’s political career was derailed by an FBI investigation of a massage parlor across the Ohio River, at which establishment Springer had paid for a prostitute with a check. Distraught and humiliated, Springer resigned from the City Council in disgrace. He has said the episode “made me see life from the bottom … The thought of ending it all crossed my mind.”

Instead — and not for the last time — Springer changed course. He held a press conference, owning up to what he did, and launched a spirited campaign to win his seat back. At a notorious St. Patrick’s Day parade, he endured mockery and jeers from the crowd (“Hey, Jerry, got a check on ya?”). He withstood the derision and ridicule with grace and good humor — he even taped a parody credit-card commercial, pitching his product as a more discreet alternative to personal checks — and eventually won back the Cincinnati public. Eighteen months later, Springer was reelected to the City Council, and two years after that, he became Cincinnati’s mayor.

As a politician, Springer considered himself a champion for the downtrodden, and when he transitioned to journalism, early versions of his show reflected that self-concept. But the culture’s interests shifted, the appetite for the sensational skyrocketed, and ratings incentives did their work: By the mid-’90s The Jerry Springer Show was not only the apotheosis of trash TV, it was something like a parody of it, its outlandishness cut with a self-awareness that seemed, in light of Springer’s former life, almost poignant.

In another life, Springer might have been a real judge or a public servant of substance. In spite of the incredulity it inspired at the time, Springer’s early-aughts Senate run wasn’t actually a piece of performance art or a non sequitur born of undifferentiated ambition; it was an attempt to reclaim a former, better identity, to live the life that might have been. It’s not too far-fetched to say Springer would have made a far less ludicrous president than the one we have, in a timeline substantially less absurd than the one we’re in.

Now, as Judge Jerry, Springer will be leaning into the idea of himself as arbiter — a departure from the strangely nonjudgmental posture he adopted on The Jerry Springer Show, which in turn clashed with the frothing condemnation of the studio and at-home audiences: ooohs and boos and smatterings of vindicating applause. But he’ll also be drawing on real expertise, putting that law degree from Northwestern to use for the first time in a while. So which version of Jerry Springer can we expect to see on Judge Jerry? An extension of the Springer Show — same histrionic guests, same thuggish audience — or an earnest attempt to embrace a lost persona?

Springer’s statements, as usual, reflect some rueful, half-ironic combination of the two.

“For the first time in my life, I am going to be called honorable,” he said in a recent press release. “My career is coming full circle.”

Jennifer DuBois is an American novelist and the author of The Spectators.