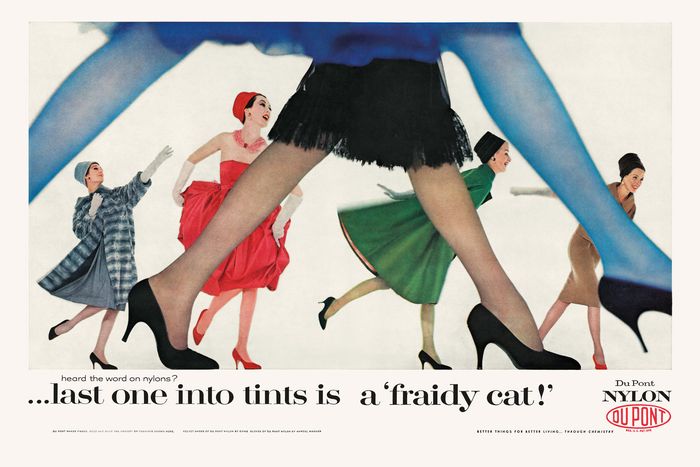

We all know the Richard Avedon style of portraiture: pure-white backdrop, classical pose, a Kissinger or Monroe (or even a man covered with bees) before the lens. But he also shot thousands of advertisements, many in color, most very different from his editorial work. His first was for a department-store line, Salymil Junior by Milgrim, in 1944, and his last was for Harry Winston in 2004. In the American century — so named by Time and Life, where some of these ads appeared — Avedon was one of the principal figures who showed us how he and his clients thought it ought to look.

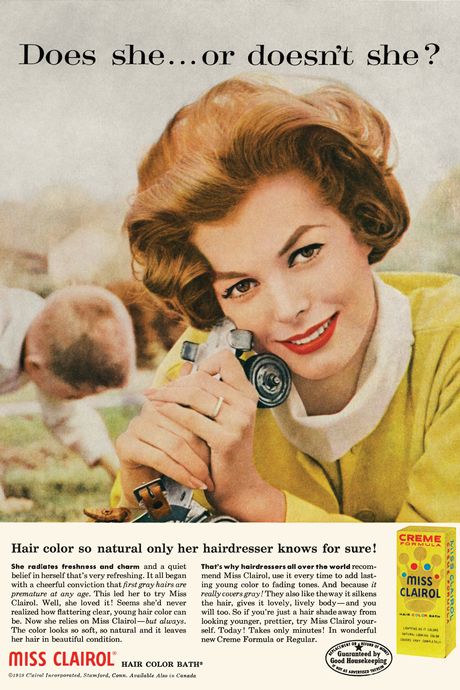

According to the first survey of his ads, Avedon Advertising (by Rebecca Arnold, James Martin, and Avedon’s daughter-in-law Laura Avedon), these photographs really worked as marketing. Before the campaign he shot for Clairol, one in seven American women dyed their hair; afterward, it was one in two. When in the 1990s Hush Puppies carried off a miracle, repositioning itself from “strictly for dorky sociology professors” to “so clunky it’s hip,” it was Avedon who helped that happen. (The photos, tellingly, focus on the models and barely show the shoes.) And they are his ads: Over the years, he increasingly inserted himself into agency conversations in order to knit together strategy and image.

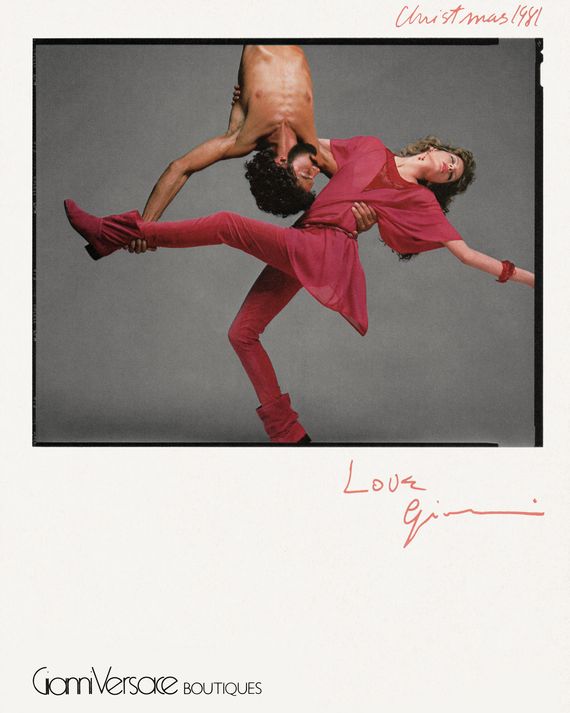

The compilers of the book make a case for female empowerment in these images, which only halfway holds up. Yes, the Versace woman commands the shirtless Versace man. Yes, it’s noticeable that African-American women like Leontyne Price and Lena Horne appear in Avedon’s mass-market ads in an era when they were rarely featured outside Ebony or Jet. But it’s impossible not to see that the image of womanhood on view in these pages is somewhat constrained, especially in the earlier decades. What is inarguable is the technical mastery in the photography, with one fantastic model’s gaze after another (even when he’s working for Royal Crown Cola rather than Dior). Make your way through the 60 years covered by this book and you come away better understanding the creation of desire.

Avedon Advertising will be published by Abrams on October 8.

*This article appears in the September 2, 2019, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!