Angel Olsen’s dream house is the one across the street from her. Sure, the neighborhood she lives in is a Zillow voyeur’s smuttiest fantasy: Bucolic? Check. Historic? Check. High median household income? Check, check, check. But it’s not the exact one she wanted to buy herself when she moved to Asheville, North Carolina, seven years ago. Back then, she hadn’t released 2016’s My Woman — a bigger, bolder, more widely appreciated assertion of the lo-fi, country-fried rock she’d been known for in smaller circles of music. And she didn’t have the savings that came with that success, but she had plans, and one of them included owning her own place, preferably the grand, beige and baby-blue one she drove past again and again, imagining the life she’d have when she moved in.

“It’s a big deal,” she says of buying a place. “It’s so nice to do, as a woman who’s not married, who runs her own business.” But when she had finally saved enough, her dream house wasn’t for sale, so she bought the one across the street. “Dreams change,” Olsen says matter-of-factly. As it happens, not getting (or giving) exactly what you want is at her core.

She greets me with a hug, but not a smile, stepping back to let me into the big brick house. Her home has a sense of hard-earned stillness — incense burns somewhere, healing crystals hide in corners, and she’s chosen a meditative, massage-therapist soundtrack that somehow manages to seem genuinely mystical through her speakers. I charge in, apologizing loudly for my lateness, disturbing the force field. Even Violet, her large, gray cat, leaps up from her resting place, annoyed.

She’s only got a few peaceful moments left to enjoy before All Mirrors comes out the first week of October and she’s back out on the road. She’s trying to modulate her energy a bit after the necessary annoyances of the day: back-to-back phone interviews and box loads of portraits of herself that needed to be signed and sent out for album promo. Earlier she went to acupuncture. That didn’t work. Then for a run, which also didn’t work. Now the only thing left to try is nicotine, even though it exacerbates the health issues that have become more prominent for her at 32, like stress-related psoriasis. She runs hot (in the Ayurvedic sense) and has been advised to avoid meat, sugar, spicy foods, and all vices. But fuck it, she really needs a cigarette, she says, leading me through the kitchen.

For Olsen, home ownership has brought up “some things” around partnership. She’s been figuring it out on all fronts: in her professional life, where she’s a self-identified control freak, but here at home, too. Living alone becomes a dozen micro decisions a day about letting people in: Do you have to explain why the wall of that room is only half painted a burnt orange, or do you just let them behold your shitty wall? Do you offer the better chair, or take the stool you usually sit on when nobody is there to want it? You want to offer apricot brandy a friend gave you, but when you discover that there’s barely enough brandy for one, do you direct them instead toward the jug of iced tea in the fridge?

“I’m trying to imagine when I have a partner one day — whoever that partner shall be that’s strong enough to be around me. Will I want them in my house? You know, with all my stuff in the places that I like them? With their weird dude shit?” She trails off, contemplating how to tolerate someone who wakes up and gets on Instagram before giving her a kiss on the cheek after she scrambled to clean her house the night before so they could come over. (That happened).

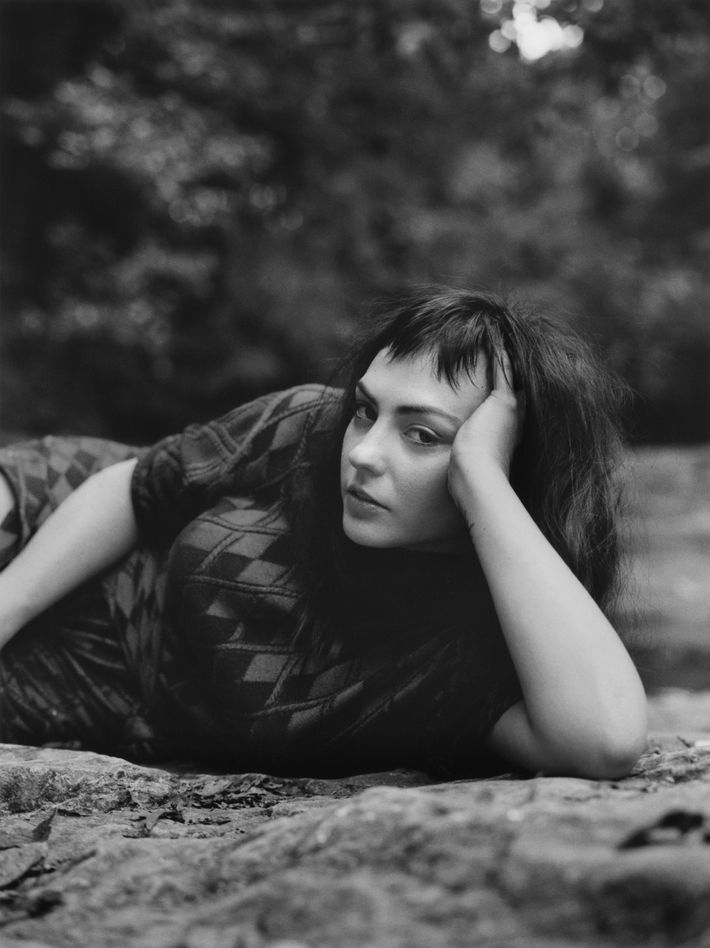

She chooses two glasses, measures out the last of the apricot brandy precisely, and grabs a green ceramic bowl to use as an ashtray on her way to the porch. While the rest of the East Coast is trending toward fall, Asheville remains, resolutely, in sitting-on-the-porch season. Olsen, in all black, sits on a stool to keep the cigarette smoke from blowing directly into my face. The slight difference in elevation between us makes me feel like a worshipper at the foot of a guru — the magic-hour light accentuates her witchy, elegant figure, like a celebrity of the 1940s but with weirder hair.

From her perch she looks out over the dense and varied greens of the landscape, pointing in the direction of the graveyard where Thomas Wolfe is buried — she sometimes runs through the cemetery, alone, because she can’t help but get mad at people who run faster than her. She points out the site of the former Highland Hospital, the mental institution where Zelda Fitzgerald, a woman with a lot of feelings people didn’t understand at the time, died in a fire, Olsen narrates with a bit of a morbid sparkle in her eye.

The only landmark I am truly interested in is seeing the bathroom where Olsen cuts her bangs. I need to know: How does she cut them? Which scissors? How often? She seems amused at my technical questions about her hair, as opposed to her music, but Olsen’s bangs journey relates more to her music than it seems — inviting the sort of interpretation of her identity that drives her crazy.

“I have a really high forehead and a really high widow’s peak. And I’ve always had bangs because of it,” she says, pushing up her hair to show her hairline. They’ve gone from the long, honey-blond, shy-girl-with-guitar bangs she had in 2011 emerging from Chicago’s DIY scene to the darker, shorter bangs she adopted as she became an avatar for intimate female sadness. For My Woman, she curled them up, embracing a brasher, rockabilly vibe. The current iteration, created by hairstylist Dylan Chavez, feels impatient (no time for curling irons), spiky, difficult, brutalist, and impossible to categorize. Are they micro bangs or something that hasn’t been named yet? Am I reading too much into her haircut?

She thinks so, but she’s used to people analyzing everything about her. Olsen’s music is intimate, personal, and at times, emotionally gutting: Unfortunately for her, she’s very good at translating sadness, angst, and loneliness. Her voice can whisper, belt, or lilt in order to get one of those moods across. She’s often compared to Roy Orbison and Patsy Cline. Sometimes Dolly Parton, but she’s suspicious of that. “I’m like, which part? Which part of Dolly Parton reminds you of me? ’Cause I don’t see any similarities really,” she says, referring to the fact that she has “Dolly Parton’s frame.”

Olsen wants to challenge all of those caricatures — she even tried her hand at disco this past summer, working with mega-hitmaker Mark Ronson on “True Blue,” a track that seemed tuned for the hours after the MDMA has worn off and the typically happy dance track takes a slightly nihilistic turn. When she does pop, it’s with a punch.

Later that night we’re at the Mexican restaurant she calls her “comfort spot.” The menu has about ten different margarita options, but Olsen’s drinking Manhattans. A few people stop to congratulate her on the recent video for “Lark,” a single from the new album. She denies that she’s the mayor of Asheville — the small-town nosiness can drive her crazy sometimes, she says, mimicking the bank teller who asked her, suspiciously, “what she did for a living” the last time she deposited her all-cash tour earnings. She has a small group of friends who “don’t care too much about her music,” though they support her — they’re the people who will watch her house and feed her cat while she’s out on tour in exchange for wine.

All Mirrors closes a chapter for her, she explains. She’s been confronting a lot: a breakup that felt like a divorce, a tour that pushed her to exhaustion and beyond. She struggled to realize that her band and crew rely on her for their livelihood and her leadership. Olsen’s parents are in their 80s — she was adopted into a family with eight siblings, many of whom were already grown up and moved away — and suddenly, she’s confronted with helping them make more decisions. It’s been a lot, to say the least.

“People think its a breakup album, but it’s really an album about changing,” she says of All Mirrors. If all you know of Angel Olsen is the sparse and weepy stuff, or if your familiarity begins and ends at the cheeky and brash “Shut Up, Kiss Me,” All Mirrors will be a bit of a shock. She’s not just singing through her issues, she’s expanding the music to reckon with the totality of them, in order to move forward. Songs like “Lark,” about the verbal abuse she’s suffered in relationships, is so dark and dense, you’ll hear it and think, “Is that a song, or is that, like, anger?” she says.

But the process has required her to enlist help. She’s been collaborating more, playing with a bigger band, and co-orchestrating to create different, lusher versions of songs she originally wrote as spare, bare-bones solo performances. “I am so fucking stubborn, and it sucks,” she says. But she’s learning. Sometimes she even lets someone else have the final say.

Perhaps inspired by the discussions of collaboration and compromise, or by the second drink, she can’t help but bring the conversation back to where we began — her house. Suddenly we’re turning into a cliché: two buzzed women discussing what it means to be single. “When you spend enough time alone, you can learn to like things and notice the small details in life that you would otherwise be too preoccupied to see,” she says, considering different kinds of partnership.

At one point, she was certain she wanted to live alone with cats. And then she was certain she wanted to be home with kids and stop playing music. “And then it was like … what if I’m gay … no, I’m not gay … maybe I just hate men … or I need to get married soon and have kids … or I don’t know if marriage is in the cards and if I have a kid maybe I’ll just have it by myself?”

I nod along to this monologue I’ve had with myself before. I feel a flash of recognition, the same way I recognize my own feelings in her music, which I tell her. She pulls out her phone to play me a song. When the 30-something women I know need confirmation of their feelings and thoughts, many listen to Olsen’s music — when Olsen needs it, she listens to Mildred Bailey. She cues up a cover of “It’s a Woman’s Prerogative.” We listen together, pressing our ears to the tiny speaker:

I don’t know who it was that wrote it,

or by whose pen it was signed.

Someone once said, and I quote it,

It’s a woman’s prerogative to change her mind.

“Oh!” Olsen nudges me. “That is the best lyric!” And she warbles along before we say good-bye for the night.