“The body has memory,” writes Claudia Rankine in Citizen. “The physical carriage hauls more than its weight.” This line struck Los Angeles–based artist Calida Rawles as she created a series of photo-realistic paintings of black figures immersed in scintillating, sunlit water.

Rawles has only recently broken into the international art scene at 44 years old, after spending over two decades selling work directly out of her studio. That said, before her debut show at Hollywood gallery Various Small Fires in February, and before her solo booth at Frieze Los Angeles opened just a day later, she had already sold her entire inventory — and to a formidable list of buyers that includes the largest art museum on the West Coast. This is no doubt in part due to her painting gracing the cover of Ta-Nehisi Coates’s 2019 debut novel, The Water Dancer. In one image, a man plunges into the depths of shadowy, glacial blue waters with his arms raised overhead as if in prayer.

For nearly a decade, Rawles has maintained a 700-square-foot studio space in Inglewood’s Beacon Arts Building, a nondescript concrete warehouse next to a community church and an auto shop. Each day, she spends between eight and ten hours in her studio, suspended by scaffolding, painting 12-by-12-inch squares of canvas. Just as Rankine fuses poetry and prose, Rawles blends techniques from portraiture and landscape painting, photo-realism and conceptual art, generating a visual language that is wholly her own.

Rawles grew up in a working-class family in Wilmington, Delaware, the daughter of a post-office clerk and Amtrak worker. “My heritage is mixed,” she mentions. “My grandmother would never count her great-grandparents as family because they were slave masters, though she knows their names.” In A Dream for My Lilith at VSF, water serves as a metaphor for transcendence, in addition to the traumatic histories of Middle Passage and Jim Crow laws across the U.S. “It makes sense from the history of segregation that so many black kids don’t know how to swim,” she says. “Their parents probably didn’t have access to pools. My parents still don’t know how to swim.”

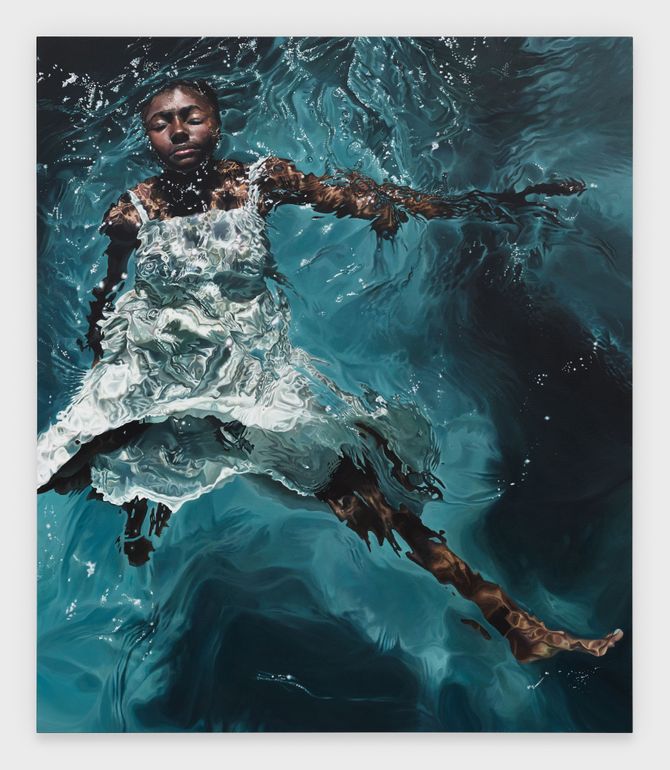

In one ethereal painting, Rawles’s daughter poses underwater in a white dress. It hangs next to another image of a young black woman floating in rippled water. Rawles explains, “Waves that come can look benevolent, but they may chip away at you. They could be microaggressions. The [subjects] can float because they can relax in turbulence. They don’t need anyone else, they’re whole.” She wanted the subjects to feel larger than life and godlike, as the subjects in Renaissance portraits of powerful white men. “I wanted her to radiate her power,” Rawles says of painting a model with darker skin. “She’s at peace, she’s centered.” The artist was inspired in part by the biblical story of Lilith, who, in her reading, “wanted agency and power and was chastised for it.” To achieve a glowing effect, Rawles mixes brown paint for their skin with iridescent gold and bronze. The enigmatic artist exudes a radiance of her own, akin to her subjects.

In intricate brushstrokes, Rawles added details to one subject’s ankles of topographical maps of Coral Springs, Florida, and Hazleton, Pennsylvania — two sites where police or security officers accosted 14-year-old black students, both girls. Two earlier paintings are named after Freddie Gray and Stephon Clark, young black men who were killed by police officers. (In these cases, the officers were either acquitted or not charged with the crimes.)

The colossal paintings are a study in contrasts. The subjects are buoyant and serene, their faces tipped toward the sun, eyelids closed. But maps of American cities where police brutalities occurred are imprinted on their bodies, reminders of the painful reality of oppression and subjugation. “Water has memory, of things that have been dissolved in it,” Rawles says. “How many people’s bodies have been lost in the ocean? Where does that energy go?” Eyelike bubbles crop up around figures, inconspicuous but pervasive — proof that that energy doesn’t disappear but perhaps, transforms.

“Her paintings are so breathtaking and refreshing,” says Esther Kim Varet, co-founder of Various Small Fires. “They’re a kind of solace for the eyes.” Varet met Rawles only nine months ago, on recommendation from textile artist Diedrick Brackens, who appears in a number of Rawles’s early paintings. Varet was struck by the deep emotional response that Rawles’s paintings provoke. Compounded with the artist’s rigorous conceptual approach, technical skill, and powerful message of social resistance, the paintings resonated with Varet. “These works come from a hopeful place,” she says, “for change in future generations.”

While creating this series, Rawles listened to books about blackness and womanhood by Claudia Rankine, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Roxane Gay, Tomi Adeyemi, Octavia Butler, and, of course, Ta-Nehisi Coates. “It seemed like kismet that we both were using water as a metaphor,” she says of their collaboration. The two have been friends for more than two decades. Coates sent Rawles unedited sections of his novel as he wrote them, revealing the manuscript to her before his publisher. Now, Coates owns four of her paintings, and after the current show closes, plans to hang them in his Harlem home and lend them for exhibition.

“Calida is a genius,” says Coates. He visited her L.A. studio in 2017, after his wife, Kenyatta Matthews, noticed their overlapping subject matter. For The Water Dancer, he says, “I wanted a cover that looked haunting.”

“I thought about how the water and sky are one, and how water has memory,” Rawles says, of interpreting Coates’s novel. “We’re all basic matter, we’re all made up of stardust.”

A Dream for My Lilith is at VSF Los Angeles through March 21, 2020.