The Cut is publishing excerpts of books coming out during the coronavirus pandemic. After each selection, join us for brief interviews with the author.

I’d gone out to buy a set of knives. The idea to update my cookware had come to me suddenly, as I was standing in the kitchenette. The pantry doors were open, and I gazed in, unmoved by what I saw. The jars of kimchi, the sacks of grain, the pair of apples to which I’d so looked forward had all completely lost their aura. I poked at a package of dehydrated noodles. Though I was hungry, I seemed to have lost my appetite for everything I loved.

I looked down. At the open neck of my T-shirt, my veins ran blue and bright across my chest, diverting nutrients to the nebula. What do you want? I wondered at it. Then I grabbed my keys and stepped outside.

At the kitchen store, caches of cutlery hung from temporary hooks. I perused the blades. I had in mind something simple and elegant, something suited to slicing the long spine of a leek, say, or chopping walnuts into chalk. For me the path to becoming a better cook would begin with soups and stews and crudités, plenty of chopping vegetables into bits, and so I went from store to store, handling the more discreet and delicate blades. I learned the meaning of “to spatchcock” and indeed witnessed a demonstration at an upscale cooking store. (Christmas was weeks away, and people had ducks in mind.) I learned what any cutlery enthusiast will tell you, that against the skin of a tomato, a dullish knife is no better than a spoon. I met a man who vacationed by the sea and who always traveled with his own set of knives, so anathema to him were the blunted instruments one finds in an ocean turnkey. I saw stiff boning blades with titanium tips, steak knives designed to slice through even the thickest cut of meat, electric butter knives that warmed to cube the coldest stick of butter. I became distracted, for a moment, by a stack of lovely colanders that nearly toppled when I touched it. Can I help you? No, no— I was only here for knives.

The last shop I visited was small and dim and specialized. The knives shone on velvet trays and under glass, like rings. A saleswoman led me up and down the darkly glinting aisles. So, she said. What is it you like to cook? I glanced at a row of cheese guillotines strung with wire. I told her the truth. I honestly don’t know. But I am about to have a baby, I said. I aimed to be prepared. She nodded. Is that right? I wondered how it was she’d done her hair, if she ate her breakfast over the sink, how it is, really, that someone finds herself in the business of selling knives. She drummed her fingers on a case of fluting blades. Come with me, she said.

There was a demonstration room in the back with a butcher’s block set with large bowls of fruit and vegetables and rows and rows of cutting boards. Together, we began to chop. We sliced apples and pears and taut tomatoes, transformed handfuls of parsley into shredded chiffon. The saleswoman showed me how to rock the blade from point to handle and back again, so that the silver edge sank, without protest, into the leather of an aubergine. She chopped like someone who never needed to eat. I was drawn to her indifference. After me, she said, and I looked on as she divided the round moon of an onion into many crescents. I learned the difference between dicing and mincing. Flecks of garlic flew. I was only just getting the hang of things when she gathered all this ostensible refuse into a tall pile with the flat of her blade and swept it into the bin. I stood stunned. Then I slowly set down my knife. I peered in at the literal fruits of our labor, the apples and onions and garlic and limes. Tomato steaks and undone aubergines. An incoherent stew. I was vindicated—certainly it was stranger than anything I’d made.

Outside, the streets were slick with ice and shoppers walked with care. On the train platform, I lingered, making all kinds of promises to myself. I lit my remaining Camels one by one and tossed them to the tracks. I wouldn’t be a smoker and a mother, not like mine. I wouldn’t forget my keys. I would be sensible, strict, warm, I’d keep the floors extremely clean. I glanced into the white paper bag that held my knives: I’d cook. Aboveground, I paused at the vegetable stand on the corner, for onions. Their weight felt human, cradled in my arms.

Earlier that week, someone had smashed through the bottom pane of the building door, and now the vestibule was full of glass. The upper pane was also frosted with cracks, and so as not to dislodge what remained, I had taken to threading myself through the ruined lower half. I did so now, clutching knives and onions to my breast.

The package was there when I emerged, settled in the slush of window shards.

Over the years I have received all kinds of mail meant for former tenants: Barbaras, Vincents, Pierres, fans of interior design and environmental-protection funds, apocalyptic newsletters whose predictions I could not support (though they seemed less alarmist to me, that winter, than they had before). This package, however, arrived without any name at all. The way it was placed, on the pretty mosaic tiles and surrounded by glass, it might have been the culprit behind the shattered door. I lifted the envelope, blew away the dust. We did not often get deliveries. Who would send something to Misha or me? All our friends lived right inside, or just around the corner. They could have saved the postage. Shards fell from the folds in the paper and trickled to the floor. The flap was sealed with professional-grade glue. There was no recipient named—just an address. The apartment number was definitely ours.

I stood for a while in the vestibule, package in one hand, onions in the other, trying to think of anyone who might want to target me with anthrax. Except that biowarfare came in average correspondence, not in hefty envelopes—I’d seen the photographs. I wondered next if I’d ordered anything online. Or perhaps Misha had? He was as off-the-grid as a computational mathematician can be, but even still. People change. I hesitated, traced the neatly suffocated seal. Then I tucked the package under my arm and stepped inside. I had committed my fair share of marital transgressions, but I was not yet the sort of woman who snooped through her husband’s mail. One can only stoop so low.

Upstairs, the apartment was empty. A rent check fluttered to the floor when I maneuvered the key into the lock. I retrieved it from the mat. The bed was made. The pantry doors were open, and I closed them again. I arranged the knives in a row. The fruit bowl, as usual, was out of fruit, and I tossed the package over its rim. Then I tore open the net of onions. They tumbled to the floor.

Bulbs retrieved, I peeled away the papery skin and fixed a rind beneath a blade. It cleaved, and the kitchenette filled with its crisp, clean smell. I turned one raw cheek to the tile top of the credenza and sliced the pearly hemisphere into concentric loops. The net emptied and the pile of rings grew. I was pulling ahead. To think that a few weeks ago I’d been suffocating my husband, and now I was chopping vegetables—for soup! It was undoubtedly a step in the right direction. By the time I ran out of bulbs to chop, the light in the kitchen had faded yet another shade toward evening, and my breasts were heavy and sore. I set down my knives. A wave of nausea passed through me like a ghost.

When I recovered, I typed “onion soup” AND “how to make” into Explorer. I began to despair. I read the recipe. I read it again. The will withered within me, like an old fruit. It had been quite enough to slice the onions without having to caramelize them as well. Then there was this business with the roux. And besides, I didn’t have all the ingredients at hand. I pillaged the drawer where Misha kept vials of spices and herbs, but neither thyme nor sherry was to be found in there. I searched “sherry” AND “substitution,” but the answer, apple cider, was no help at all. I drifted, as one does, to AOL, where the home page blitzed with deals. I checked in on the waxing kit chat, where I’d left a simple Q. Some patient souls had replied:

qwerty123: how often do you have to, you know … ?

Fantabulist: if wondering, fuck yes it hurts.

JSTORED: oh, hun. come back when ur 18!!

I sighed. I hadn’t felt eighteen in weeks.

I opened Napster to see how my favorite users’ libraries were coming along. I liked peering into other people’s hard drives, other people’s minds (stealing, Misha said). Onyx123 stocked songs by the musical wing of Neue Slowenische Kunst. I looked them up. Albums stored in others’ libraries migrated into mine. I wondered what, to Misha’s algorithms, my browsing history implied.

When Misha returned, the kitchenette displayed the evidence of my abandoned search. The screen was filled with Viking shipwrecks discovered along the Nova Scotian coast, the credenza was replete with onions, whole opalescent piles, and I was at the sink, sharpening my knives. He stood for a moment in the doorway, bucket and wand in hand. Is everything all right? I held up the silver yield of my errands for him to admire. I was well on my way to becoming a cook, I announced. Or at least a sharpener of knives. Misha took my wrists and gently guided them to the table. He’d left for the Rockaways at dawn, now he kissed me and I breathed him in: onions and sea and salt. I leaned into the fact of him. His coat was cool against my cheek, and when he spoke his words muffled in my hair.

Babe, he said. Is everything okay?

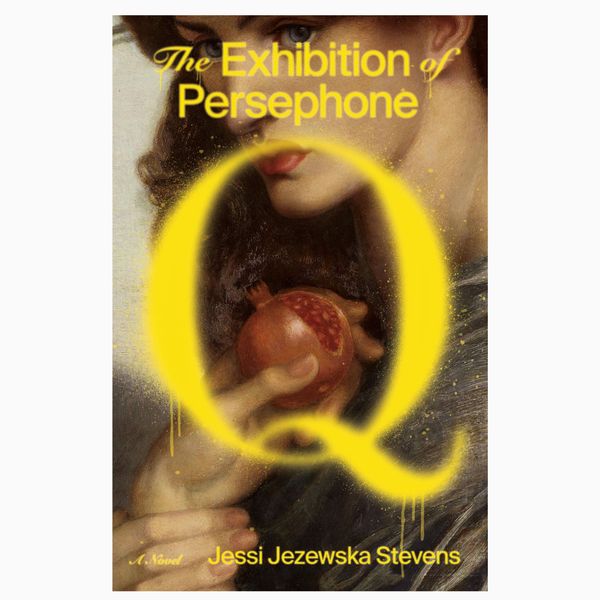

Excerpted from The Exhibition of Persephone Q, by Jessi Jezewska Stevens. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2020 by Jessi Jezewska Stevens. All rights reserved.

In Jessi Jezewska Stevens’s debut novel, The Exhibition of Persephone Q, a young woman living in Manhattan immediately after 9/11 reckons with becoming a mother, develops insomnia, and finds herself featured in a mysterious photography exhibition against her will. Kerensa Cadenas, the Cut’s senior culture editor, spoke with Stevens about the release of her novel, which came out on March 3.

Reading your book felt isolating in the same way I’ve been experiencing the world lately. What was your inspiration to write this?

I had a friend tell me recently that she’s a little bit nervous about me ever publishing a second novel since I’ve managed to string this first along a series of disasters. It’s set just after 9/11 and I was writing it leading up to the 2016 election. I thought that setting it right after 9/11 would help foreground what was a contemporary mood. Then of course I published this just before we really went into lockdown. I have been reflecting on ways in which Percy’s isolation, her individualism, her stubbornness, her denial, is also reflecting the current moment as well.

I noticed that Percy sees a psychic many times throughout the book. Is that meant to be a reflection of her anxiety and the way things felt in the city right after 9/11?

I think there’s a lot of searching and desperate attempts to make meaning in the book. One of those is Percy’s constantly consulting her psychic and really hoping that she can find some readymade answers or find a story that would offer an explanation to the kind of confusion and anxiety that she’s feeling. There’s this idea of searching and trying to make meaning and then possibly — towards the end of the book — realizing that that search has to be enough.

If you buy something through our links, New York may earn an affiliate commission.