Chances are, you know Yoshitomo Nara’s work. Despite being an artist who often foregoes the spotlight, Nara’s remarkable oeuvre — much of which is anchored by portraits of children rendered in lurid colors and hyperbolized expressions — has cemented his status as one of the world’s most salient contemporary artists.

Influenced by popular culture in both Eastern and Western society, Nara explores deeply humanistic themes of solitude, insurgence, and spirituality in a myriad of modes. Despite those innate complexities, Nara is often relegated to a limited assessment that he not so silently resists (“humans might have a common personality based on the town and environment they were raised in … but you shouldn’t be able to judge people under the same standard”).

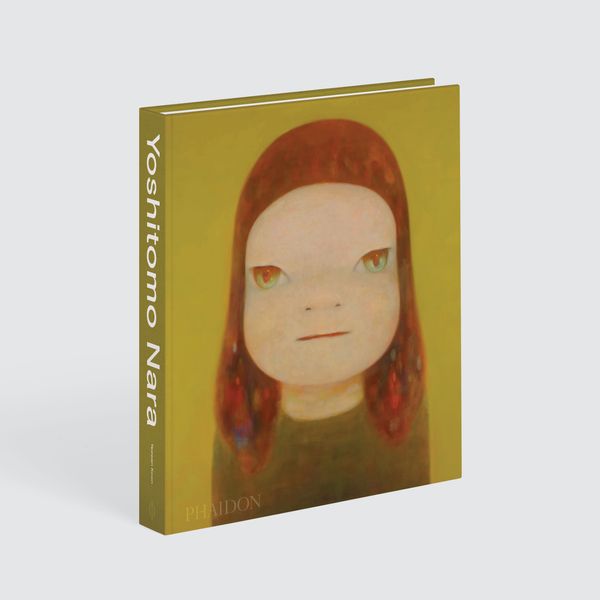

Aware of this narrative, Yeewan Koon, associate professor and chair of the Fine Arts Department at the University of Hong Kong, embarked on a journey to “tease out themes that are often left out [surrounding] Nara, and to connect his work across different mediums.” Her latest book, Yoshitomo Nara, serves as the definitive tome on the renowned artist. In celebration of its publication, the Cut talked to Koon about everything from Nara’s interest in photography, to the toll that immense popularity has had on him, to her relationship with the artist himself.

What do you consider Nara’s methodological approach to be?

Nara is not a cerebral artist nor a conceptual one. His methods are more grounded within his own environment and imagination, and he is driven by feelings and guts, which means his aesthetic decisions are seldom linear, though he does work within a recognizable framework of formal methods.

What is kawaii, and how does it manifest in Nara’s works?

Kawaii is the response, the “aww factor,” and in Japan there is a more nuanced interpretation of what that is in comparison to the way we use “cuteness” in English. I think survival is something that runs through many of Nara’s works. Survival here is about resilience and self-determination, rather than reflections on death or trauma, and that’s a vital distinction. Nara imbues his figures with a strength of character and a sense of autonomy as if they belong to their own world, and these are aspects that are part of their “kawaii-ness.”

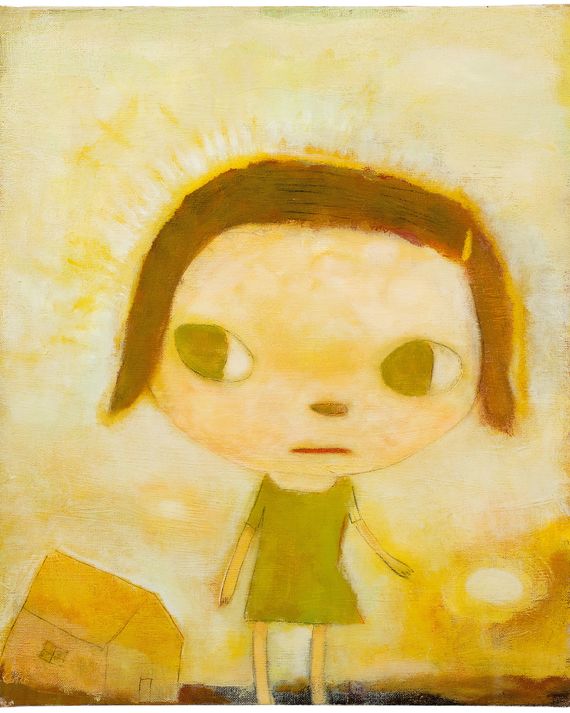

His seminal work, The Girl With the Knife in Her Hand (1991), is an example of this. But we see this in his earlier works too: In Romantic Catastrophe (1989), which shows his transition to single-figure compositions, Nara explores the ambivalence of kawaii (which can be dark and sweet at the same time). He has made his child figure much larger so that she looms over her surroundings; one hand is raised and now transformed into a flaming torch, and a thin halo circles her head.

What do you find Nara’s most compelling medium to be?

Maybe drawing — it certainly is the medium that underpins all of Nara’s work. I particularly like his doodles. It is here you see him at his most free.

Can you talk about the practice of gift-giving and how it serves as a pillar in so many of Nara’s projects?

Nara’s Yokohama show “I DON’T MIND, IF YOU FORGET ME.” (2001) was a very important one, not least because the museum was supporting an artist who was considered controversial by the Japanese art establishment at the time. When he first started preparing for the show, he was still in Germany, but his fans made him feel connected to Japan and this helped him enormously. Getting them involved in the exhibition (making dolls and then later displaying them as part of the show) seemed almost a natural way of extending their relation through these continuous reciprocal acts, and it also gave him a way of challenging the museum (as well as the art establishment) as a top-down institution.

You say in your book that Nara’s work undergoes an important stylistic shift, “from repetition to erasure,” as he begins to create small differences within his portraits. What do you credit this shift to?

Part of it was a response to how he was being pigeonholed as a Superflat artist, or having his work seen only from the perspective of Japanese visual culture of anime and manga. But he was also using erasure at this stage to try and break out of his own comfort zone. At times, it was very aggressive. You see this in After the Acid Rain (2006), which is not a “sweet” painting — there are pools of reds and maroons, like claggy bits of molten swamp around the child that sucks the air out of the scene. Within all this stands a semi-submerged child with her too sentimental, giant eyes, and we cannot help but feel uneasy, even threatened by it all. The ominous edge to this painting is made more obvious by the title. It was made at a time when Nara was coming out of his struggles with his newfound international fame and constant demands for his paintings. Today, Nara continues to use erasure, but now they are less about destruction and more meditative.

What do you feel has been Nara’s most ambitious work or works thus far?

I can point to one set of works that I think are real turning points, and it is ambitious because it could have easily failed. His 13 giant bronze heads (2012), made during a residency at Aichi University of the Arts, are important because of how they provided Nara with creative release after the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, followed by the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident. The 2011 disasters happened on the doorsteps of Nara’s hometown, and in the days that followed, he and his mum drove around villages and towns dropping off much-needed supplies to families in need. For a while, Nara could not paint, and instead he turned to working in large sculptural forms in clay. With these, you can almost see him throwing his body against giant clumps of clay, doing battle as he pulls, tugs, and molds the clay into heads. The physicality of his body is deeply imprinted onto the surface of each one of the 13 heads.

Is there a way in which you think the viewer is meant to engage with Nara’s paintings?

What Nara is trying to do, in bringing his viewer closer to the surface of his canvases, is to encourage slow looking by turning his attention to the treatment of colors. I think he succeeds in doing so, especially from 2012, and Miss Spring is an example of that. And if you consider that Nara’s paintings are essentially simplified figures of a child, the idea of spending a long time slowly looking is almost radical.

Tell me a bit more about the process of writing this book.

This turned out to be a much harder book to write than anticipated, which is a poor reflection on my own ego. Indeed, that deception of simplicity became the driving force behind the writing. Nara has formed a 30-year-long career based on a very simple image: the child figure. I think it is fair to say that, for many viewers, Nara’s works are all either very similar or that they have such immediacy they are seemingly knowable, so why is there a need for a 50,000-word book? My job was to tell a compelling story that challenged that myth of simplicity. I wanted to tease out themes that are often left out of narratives on Nara (the importance of margins, his antiwar stance) and to connect his work across different mediums. Nara is a very private individual who needs to understand why certain questions were asked before he would answer them. It was never a case of, “Let’s just talk.” We established some ground rules, the main being I can write whatever I wanted, and he would only fact-check. We also maintained a healthy distance to ensure critical objectivity — for example, there were times when Nara’s paintings didn’t quite work or they were becoming too repetitive, and it was important to talk about those moments, too, as part of his working process. Nara was very adamant about not interfering with my work, and he gave me a lot of freedom. In return, I respected that trust by trying to write a book that I hope gave insights and critical perspectives.

Is there a particular anecdote that resonated the most with you?

Since 2014, when I first got to know Nara, we often walked through his exhibitions together and I would ask him nonstop questions about his art. These were never light conversations. Indeed, I later found out that, after one session, he was so exhausted talking to me he went back to his hotel to sleep, foregoing other meetings. Ever since, when he sees me, he would either challenge me to ask him tougher questions, sometimes even thumps his chest, or he would pretend to faint and play dead on the floor when he saw me coming.

What is one thing that surprised you the most in the development and creation of this book?

I would say seeing Nara in Japan is the only way to really understand him. He exerts real authority there — he is a rock star — and with that comes a need to control his privacy, to make sure his words are not taken out of context, and [to ensure that] there is a certain sense of responsibility that comes from having that power. On the other hand, he is also a very regular person. I attended his 59th-birthday party, and it was a small gathering at a friend’s small office on campus with everyone bringing some snacks or drinks. It was a group of about ten people, and we were all snuggled around a desk eating seaweed chips, potato salad, and drinking beer and wine. But his 60th celebration was a rock concert where all his music friends paid tribute to him. It was more than three hours long, and if you have never been to an underground Japanese rock concert, there is nothing like it. There was certainly no potato salad in sight.

Scroll below to see more works from Yoshitomo Nara.