The Cut is publishing excerpts of books coming out during the coronavirus pandemic. After each selection, join us for brief interviews with the author.

In 2011, I was naked aside from a chest-less green gown in a Canadian cosmetic surgery office located on the second floor of a mall on the outskirts of Toronto. This man was cupping my breast and swirling it all around, he was going to cut it off, along with the other one, in a few hours. The doctor held my boob through a blue latex glove, moved the fat of it around as if he were a claw gripping a plush thing in an arcade machine. He drew a fat black line across my skin where my breast usually lay.

I’d just signed the form that said “paid: $6,043.00/male reconstructed chest” and was slowly realizing that these were my last few moments with breasts. I was so busy getting the money together that I hadn’t taken any time. Five thousand of it came from a settlement after I got hit by a car crossing the street in New York—you got lucky, my friends said about the money and I agreed. For now, healthcare can cover top surgery, it didn’t then. I realized I hadn’t said goodbye to my potential to give milk, any of it. Cold in this man’s hand, they were beautiful. Historically, they were the most complimented parts of my body, aureoles dark as my grandmother’s face, a gift from her that I was supposed to empty into a baby’s mouth.

I looked at myself in the mirror over the doctor’s shoulder. My brow was wrinkled, my frame seemed so small. He let my breast fall and stood up from his stooped position. It lumped there. I looked down at it.

Look okay? he asked.

From a part of my throat that was surprisingly high, I said great, it looks great. I tried to imagine the lines as scars. I tried to imagine how I’d look with big hips and no breasts, a subtracted pinup, some gasp.

A number of my friends had gone to the more famous doctors (Brownstein, Garramone) in the US. I’d decided on this one because he was one of a very few who didn’t require a letter from a psychologist, didn’t require a written promise from me for a full “physical transition” either. In 2011, the US wasn’t interested in having a bunch of us in-between and running around. They didn’t want us going halfway anywhere. So, to Canada!

A few years after I had surgery, I was at the $20-for-an-entire-day spa in Los Angeles’s Koreatown and a woman who’d been eyeing me for the better part of an hour cornered me to ask if mine was the same surgery that Angelina Jolie had.

The best I could do that moment was “sure.”

You were afraid you’d get cancer?

Sure, I said again.

You’re so young! You don’t want to get implants? She pulled at her own nipples in gesticulation.

Nope, I said.

Weird, she responded, then lay back down on the wooden sauna bench, put her towel over her eyes.

Naked, I look like Pan, a satyr or something, I still have hips, little legs, I’m hairy with a thin waist, a slight chest, chewing gum nipples, broad shoulders. I’m so small. I’ve edited my body, mixed my skin around with some money.

Now, twisted, puckered scars serrate my chest and sometimes strange women on the beach cup me by the elbow and say, Sweetheart, just because you have cancer doesn’t mean you can walk around like this. They mean, it’s still obscene for you to be topless even though the lumps of them have been tossed out into a biohazard bag in some fluorescent Toronto storeroom, even though after surgery, your boobs became singular—a chest.

I remember a therapist once, a counselor, talking to me off the record about a couple she called “the interesting couple.” They were once lesbians, but one member of the couple was coming out as trans and they were in therapy trying to deal with that and the frustration of seeing themselves possibly as heterosexual, as queer, as something other than lesbian.

The therapist was giddy about using dysphoria as the diagnosis and giddy about telling me: Apparently, gender dysphoria is “a difference between one’s experienced/expressed gender and assigned gender, and significant distress or problems functioning.” It has to last at least six months.

“Until the early 1990s, when trans communities began finding strong, collective voices, medical providers’ explicit goal for gender transition was to create normal heterosexual men and women who never again identified as trans, gender-nonconforming, gay, lesbian, or bi,” writes Eli Clare in Brilliant Imperfection. “Transition as an open door, transness as defect to fix, gender dysphoria as disability, transgender identities as nonpathologized body-mind difference—all these various realities exist at the same time, each with its own relationship to cure and the medical-industrial complex.”

Diagnosis is from the Greek diagignoskein, which means a discerning, distinguishing. The root dia- means “apart.”

When the doctor left, I flipped through OUT magazines giggling, a nurse put an IV in my arm. There was a stream of nurses in the office for the next half hour until one of them said everything was ready and encouraged me to follow her.

I was jolted by her sweetness. I’d been working at stoicism, tried to rein in my feelings as I walked into the operating room on my own power.

Is this how cosmetic surgery always goes? The scene was nightmarish. Awake and elective, I hoisted myself onto an operating table and lay there. I was surrounded by several people in head-to-toe scrubs, cleaning implements, scalpels, things. They moved without looking at me. A fluorescent light beat.

When I woke up hours later, a nurse was shaking me awake. She was saying it’s time to get up and was struggling to put a brace around my chest to keep the newly reconstructed skin in place. I welcomed the feeling of the brace, my body was a loose glove. She handed me a juice box, apple, I think, and shooed me off the bed and into a wheelchair.

I sipped on my juice box and felt heavy in the canvas cup of the wheelchair.

Three weeks after I had surgery, I sat on the toilet where the light was best and opened the brace on my chest. I had to have a friend take my stitches out because a drive back to Canada for a fifteen-minute procedure seemed absurd, and there was no nurse or doctor in the area that had any idea about top surgery. I was living rurally and was scared of the repercussions of going into a doctor’s office with this new thing. My friend stood there with the scissors as if with a wand, snipped away the first blood-soaked sponge from my new nipple. I almost threw up from the feeling. It wasn’t pain so much as a weird, sensitive numbness that felt like stomach lining, tugged.

They peeled the sponge back to reveal a tiny crater and winced, seeing it. They squinted and picked with a pair of tweezers at the tiny striped stitches—tons of them knit into my crushed new nipples.

Their wince was gorgeous.

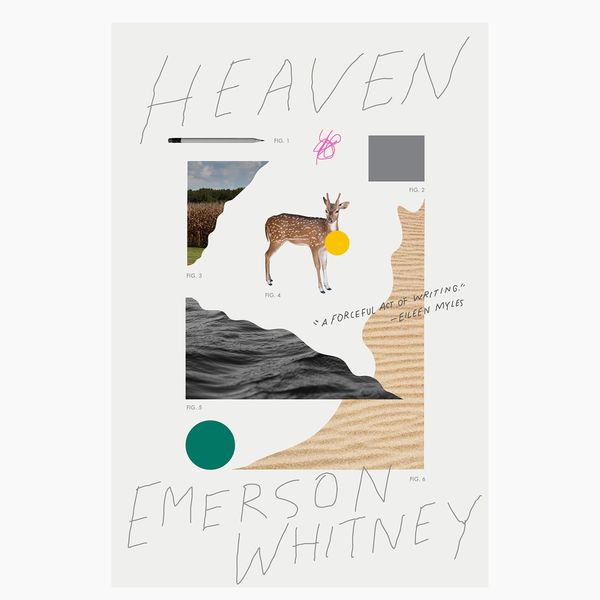

Excerpt used by permission from Heaven (McSweeney’s, 2020). Copyright © 2020 by Emerson Whitney.

An exploration of selfhood and transness, Emerson Whitney’s memoir Heaven (April 14) probes their relationships to their mother and grandmother and how they influenced their ideas of womanhood. Kerensa Cadenas, the Cut’s senior culture editor, spoke with Whitney by phone about what it was like to write their memoir and the work they drew upon to complete it.

Why did you want to write this memoir?

I didn’t really have a good reason. I think if I had a reason, I probably wouldn’t have done it. This is the hardest thing I’ve written, and it probably will remain that way. I don’t think I will ever rip off my arm in the way that I did to write this.

I love when writers are able to distill academic theory down into something that’s actually relatable to a nonacademic audience. Why was it important to you to bring that into your memoir?

I appreciate the way theory uses sometimes experimental language to pull the rug on commonsense concepts. I do think theory is being made in communities and by people with marginalized identities and subject positions and isn’t being called theory. Sometimes theory is only given that label when it fits a certain canonical, academic way of being shared.

If you buy something through our links, New York may earn an affiliate commission.