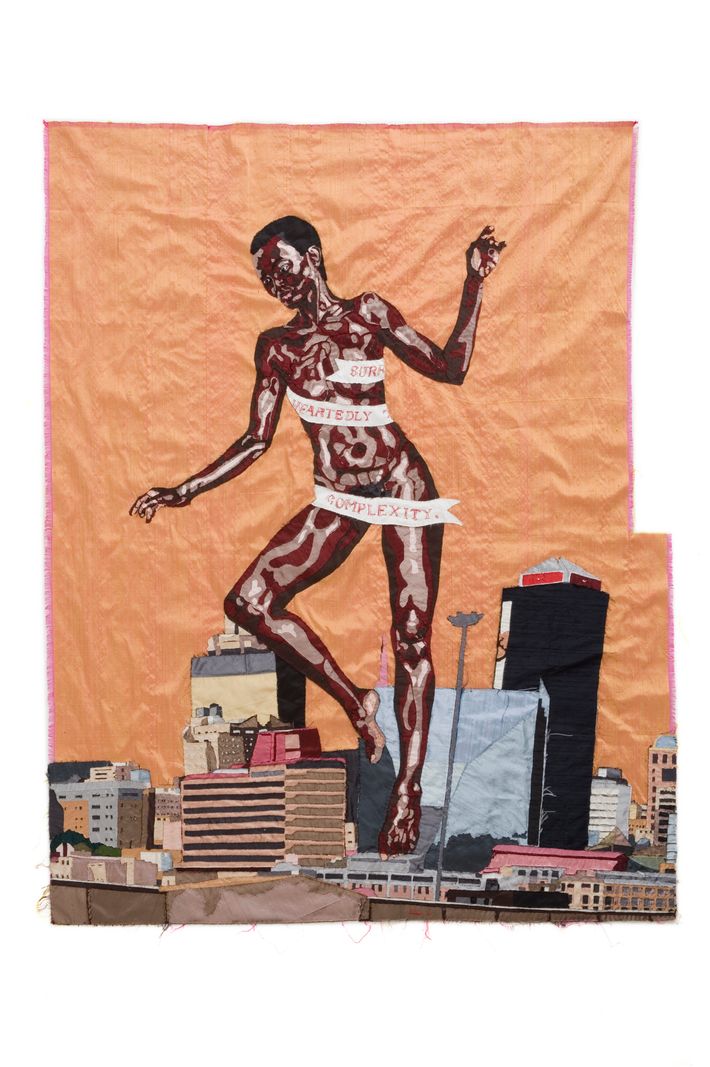

In 2010, using raw silk fabric and threads, Johannesburg-based South African–Malawian textile artist Billie Zangewa hand-stitched and embroidered an image of a larger than life Black woman rising up from the urban cityscape of Johannesburg. The weightless woman hovers sylphlike in the air, above the roof of a diminutive building, delicately holding her balance on the toes of one foot, as though dancing on pointe. It is a stance that conjures up the beauty of dancers who toil to discipline their mind and bodies until they master them in ways most of us can only dream of. A long strip of cloth is missing from the right side of fabric, misaligning the tiny pinked frayed edges running around the perimeter of the rest of the silk canvas, an imperfect frame. The tapestry is titled, “The Rebirth of Black Venus.” It marks the threshold season for Zangewa, who had been making art for over 20 years already, when she made the decision to put herself first over any and all cultural and societal expectations of who she should be as a woman. I spoke with her by phone at her home in Johannesburg for the Cut, to learn more about the motivations and ideology behind her work. “I made a choice between being a potentially unhappily married woman that society sees as safe or showing up for myself and choosing my own freedom,” she told me.

Zangewa made that decision ten years ago, but her art has always dealt in themes of self-exploration, telling personal stories of love, femininity, and the healing nature of domesticity. “I want to be the best me possible,” she said. “I’m constantly asking myself, how do I develop greater self-awareness, and how do I engage with other people in a loving and generous way that still honors myself and is self-improving while also beneficial to those who bear witness?” Her most recent solo exhibition, “Soldier of Love,” was a ten-piece show that closed at Galerie Templon, Paris on June 6. The title is a reflection of Zangewa’s commitment to explore the idea of love through the particularities of her identity as a Black, multicultural African woman, as a single mother and lover, and as an artist working from home.

Her commitment to self-examination has at times meant reexamining narratives she picked up as a child born in Malawi, and later raised in Botswana. “My Malawian father was born free and he was educated,” she explained. “But gender roles in Malawi were traditional. Women stayed at home minding children while the men went to work and made money. My father treated me differently than my brothers and it wasn’t a good thing. It planted a seed in me to find some kind of personal freedom and empowerment. I knew from a young age that I had to learn how to take care of myself in a system that showed preference for boys.”

It was Zangewa’s mother who helped her imagine other possibilities for women. Born in a small village in South Africa under an oppressive system where she wasn’t able to go beyond primary school, her mother chose to raise Zangewa in Botswana, sparing her the trauma of apartheid, and pushing her instead to get an education. She explained to me, “Botswana was a politically free country with strong women in parliament, women running businesses and raising children on their own. That’s where I found models of being a woman and began to believe that whatever dream I had was possible.”

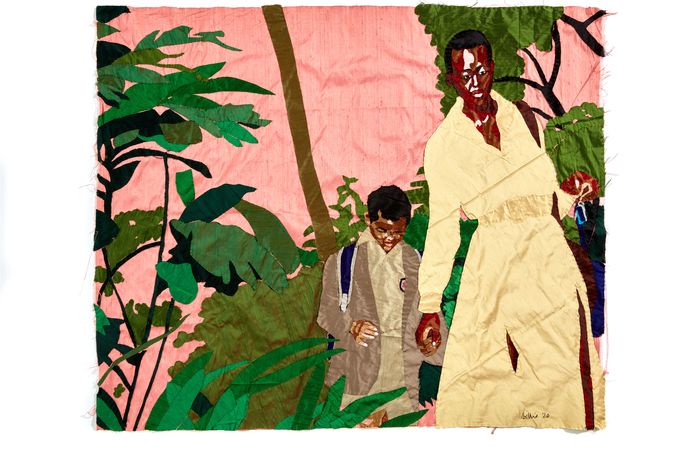

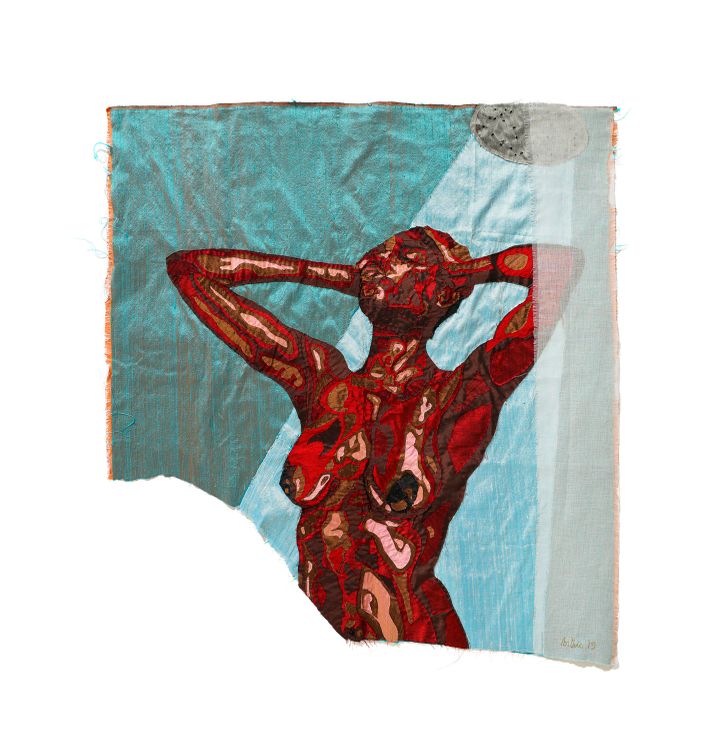

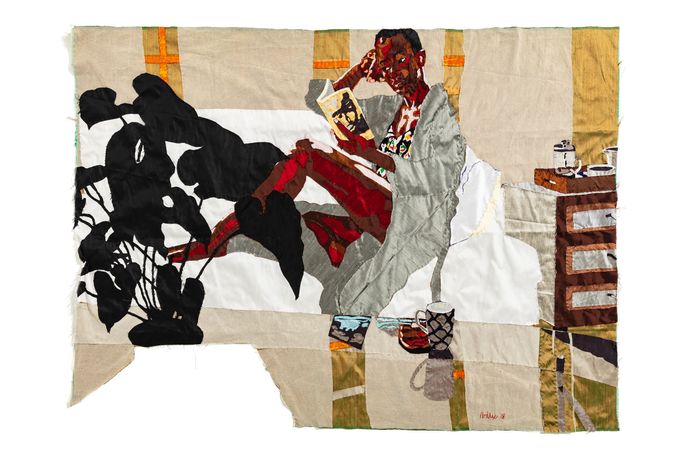

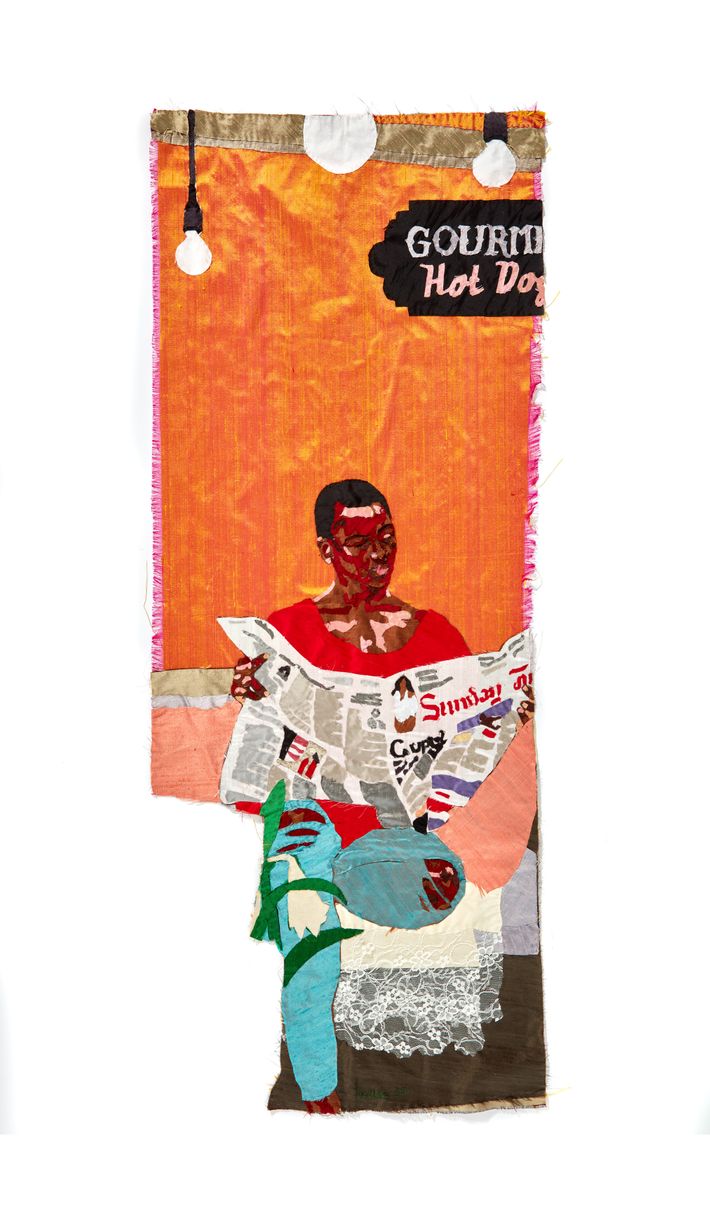

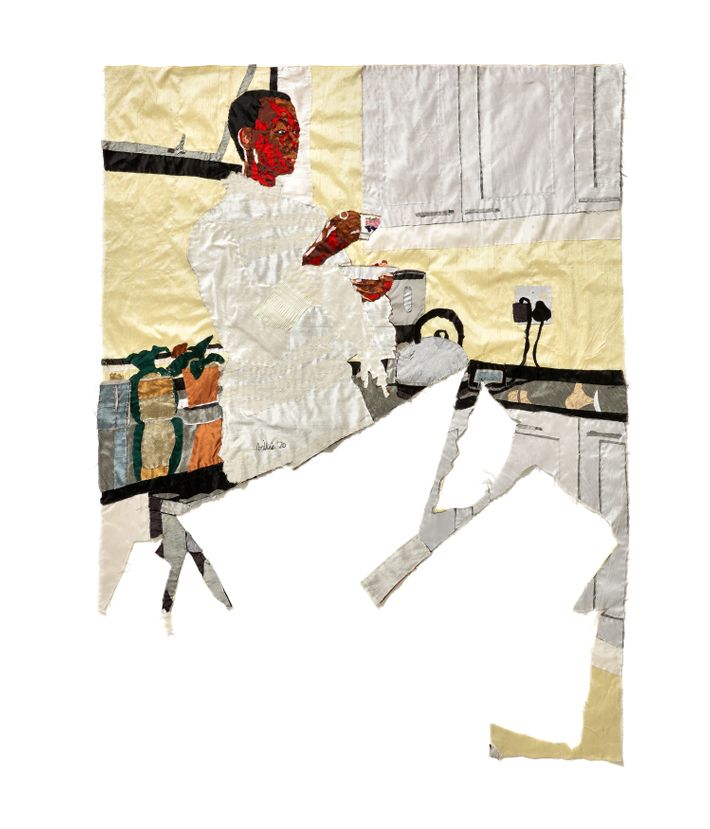

It was also the place where, Zangewa said, she saw her mother and other women find strength and healing in the quotidian: sewing, nurturing their children, and making homes for their families. It left a lasting impact on her, one that would manifest in her artwork: “I now experience it myself, how much effort it requires to keep a home together, to manage everyone’s emotions and to raise children, in my case a son, who will love and protect women. And all the while, you have to find ways to stay sane, to take care of yourself.” Zangewa’s depictions of women — walking a child to school, juggling a baby on one’s hip while trying to make breakfast, stealing away for a shower or a quick cup of tea alone at the end of the day — not only elevate women’s daily work and showcase acts of self-care, but also recognize the humanity of Black women in a way that the cultural imagination have not always permitted or embraced.

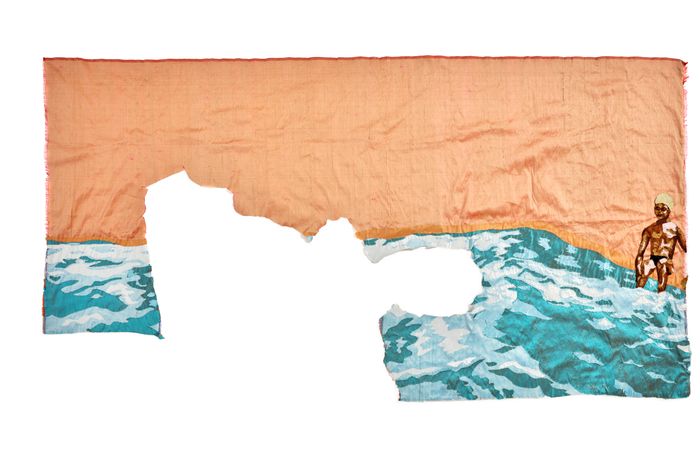

Zangewa chooses to work with fabric and thread, hand stitching, sewing, and embroidering. She explained, “Fabric, this thing we all have a daily relationship with, is often dismissed by the world as mundane and unimportant, much like the daily, mundane work that women do to keep a home, a community and a society going. I wanted to use this dismissed cultural thing to speak against patriarchy by creating powerful images about the importance of another dismissed thing, domesticity and the ordinary but important aspects of women’s daily life and work in and around the home.” What’s more, the act of sewing in itself held a significance. “In those hours together, my mother and these women were figuring out how to make better decisions about their lives and how to keep cultivating resilience against the hardships of life.”

She uses imperfect pieces of silk samples because, as a fiber created during the transformation stages of living creatures, she considers it symbolic of her work. As irregular pieces, the material also mirrors the imperfections of our human lives. We can still stitch and thread together something beautiful with what remains, Zangewa believes, despite our pain. “In art we’re often drawn to the grand gesture, but I want to keep asserting these smaller moments in our lives. Even the small choices we make about clothing on a daily basis can say something about how we see and understand ourselves. In ‘The Rebirth of Black Venus,’ the full sentence on the ribbon says, ‘Surrender whole-heartedly to your complexity.’ That still speaks to me today when I think about my ongoing journey and about being a soldier of love.”

Billie Zangewa is represented by Lehmann Maupin Gallery in New York, where her next solo show is scheduled for October 1st 2020.