When Hillary Clinton endorsed Representative Eliot Engel, a 73-year-old Democrat from New York who hasn’t faced a real primary challenge in 20 years, many progressives took it as a sign: The party Establishment was nervous. Engel’s opponent is Jamaal Bowman, 44, a former middle-school principal running far to his left; he bills himself as “a Democrat who will fight for schools and education, not bombs and incarceration.” Clinton’s endorsement of Engel was noteworthy and carefully calculated — it’s her only down-ballot one so far — but it didn’t seem to shake Bowman. A day after it came out, he posted a video of himself jubilantly dancing in his car to “Night and Day,” by Wayne Wonder, with the caption “Just vibing.”

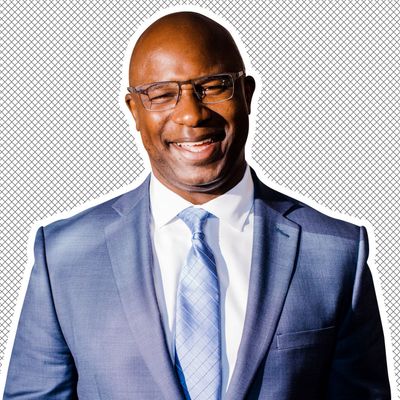

Bowman, who has a megawatt smile you can imagine helped him in his former capacity as a person in charge of hundreds of adolescents, is running on policies like Medicare for All, a Green New Deal, and removing funding from the military and police departments. He’s racked up endorsements from every major progressive organization; Engel, conversely, has the support of centrist Democrats like Nancy Pelosi, Andrew Cuomo, and Chuck Schumer, as well as a conservative super-PAC. He’s the head of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, where he is considered hawkish on foreign policy, and has major donors in the weapons-manufacturing and defense industries. He voted for the Iraq War and against the Iran nuclear deal. Constituents have demonstrated at his offices in opposition to his lackluster environmental record and his refusal to take the No Fossil Fuel Money pledge.

For obvious reasons, Bowman has been compared to Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, another younger progressive from the Bronx who mounted a long-shot campaign against a powerful Democrat, one closer to the center of the political spectrum than the left, who’d held on to his seat for years. As with AOC’s victory, ousting Engel would truly shake party foundations. And Bowman has a very real chance of doing so: A Data for Progress poll recently had him up over Engel by ten points (Engel’s campaign countered with an internal poll showing its candidate up by eight). The prospect of a Bowman win is thrilling for those who want to see candidates pushing for real social and political transformation actually build power in a state that has long been blue. It is also energizing for the progressive movement at large, after the blow of Joe Biden as the presidential nominee, with his disappointing records on economic and racial justice. Bowman’s win would be a bellwether of the good kind, finally.

But in a David and Goliath scenario, the David winning is always an aberration, even if a celebrated one. For progressive candidates, being compared to AOC can be a double-edged sword: It generates interest and enthusiasm but also can be used to summon the fear that what happened in her district two years ago was a fluke. The framing is designed for maximum impact. But it’s reductive, and it belies a far more significant political narrative taking shape: the idea that Bowman, as a candidate, is now eminently sensible. His challenge isn’t pie in the sky; it comes from the ground.

The twin crises of the coronavirus and police brutality that erupted in the past few months have made it clear how qualified Bowman is for the position he seeks. As a Black, working-class resident of his district, which covers the Bronx as well as wealthier areas like Westchester, plus the suburbs of Mount Vernon, Yonkers, and New Rochelle, Bowman is much more in touch with those who have suffered the most in the devastation wrought by COVID-19. Engel voted for the notorious 1994 crime bill, which fed the mass-incarceration crisis; Bowman had his first interaction with violent police when he was 11. The difference in each candidate’s relationship to the community was crystallized in an almost absurdly representative moment, when Engel, who had received heat for spending most of his time in his house in Maryland during the pandemic, showed up to a press conference organized in response to protests over the death of George Floyd. Engel was caught on a hot mic asking to speak; anxious he wouldn’t be given time to do so, he could be heard saying, “If I didn’t have a primary, I wouldn’t care.” He repeated himself: “If I didn’t have a primary, I wouldn’t care.”

In this new national context, Bowman’s challenge has become so compelling that State Senator Alessandra Biaggi — who won her seat alongside a slate of New York challengers to the Republican-controlled Independent Democratic Conference in 2018 — retracted her endorsement of Engel in favor of Bowman. “At the end of 2019, I took a pretty firm stand that this was not the year to primary Democrats. We had a very important presidential race coming up, perhaps the most important of our lifetimes, and my focus was going to be on that,” she told the Riverdale Press. “Since then, the world has changed.”

Michelle Goldberg of the New York Times wrote that Bowman’s run will be “a test of whether the energy on American streets translates into votes.” I would argue that, even before the votes are in, the way his race has panned out is evidence of something bigger happening. Bowman received endorsements from Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren. To some, both former presidential candidates have been frustratingly conciliatory toward their previous competition, Biden, citing a need to unite the party in the face of Donald Trump, despite vastly different visions of how we should proceed if he is defeated. The fact that these two threw their weight behind the middle-school principal — and against the incumbent they knew — shows that some very powerful people sense a sea change, no matter what the outcome is tomorrow. They want to be on the right side of where the wave crashes. Bowman has a lot to smile about.