In August, I spoke for a second time to Alessandro Michele, Gucci’s phenomenally successful creative director, who was staying at his Umbrian estate about two hours from Rome. Ever since our first conversation over WhatsApp in June, something had gnawed at me.

Michele’s approach has been called curatorial, maximal, even excessive. But that’s not the feeling I got during our first meeting. It was innocence. He was so gentle, even dreamy. Although I knew his work well enough, one thing our conversation made abundantly clear was just how much Michele has the support of his CEO, Marco Bizzarri. Without that backing, no designer could have done what he did in 2015-16 — essentially throw the baby out with the bathwater. Michele’s fashion was geeky; it relied on vintage styles; above all, it was unsexy. Nothing could have been further from the knowing glamour of Tom Ford’s Gucci. It was a creative shift that worked. In the past five years, Gucci’s revenues have more than doubled to $10.5 billion.

Where Ford expressed the grown-up world of sophistication, Michele expresses childhood — before we’re spoiled by civilization. By fashion! He shows many gawky-chaste long-sleeved dresses — and, often, one or two outfits symbolizing authority, like a matronly gray suit that appeared in his February show. Michele’s clothes are not just different from Ford’s; they are the opposite. “From the start, I was not thinking about fashion,” he said. “I was thinking of the beautiful shirts on our teachers. I was thinking of the beautiful things I saw on my mom and my granny.”

Michele owns 35 editions of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, and, as countless critics have pointed out, a key theme of Alice is the insanity of adulthood. Which, of course, she rejects at the end. “I love that it is kind of a psychedelic experience of your childhood,” he told me. “Because I’m not really sure of what is real and what isn’t real. It depends on your perspective. Fashion is a piece of this huge story. I always say it’s a floor in between. It’s like the hole that Alice enters.”

Gucci’s success affirms why trusting a creative’s intuition, and not market data and surveys, matters. Michele, who spent the lockdown in his Roman apartment, said he talked to Bizzarri early on about reducing the number of annual shows from five to just two. He felt exposure to so much fashion was lessening its cultural power. “People don’t care,” he said. Above all, he worried that the industry should have made changes before a crisis like the pandemic hit.

But that naïveté sometimes gets him in trouble. Sweaters from his February 2018 show half-covered models’ faces with knitted balaclavas or yanked-up turtlenecks with an outlined cutout for the mouth, “suggesting a postoperative state,” as one writer put it. One of those sweaters — in black, with a red lip outline — led to charges of racism against Gucci a year later, when someone on Twitter posted an image of it as an example of blackface. Bizzarri flew to New York for a meeting organized by the design legend Dapper Dan, (who began partnering with Gucci after a kerfuffle in which the brand appropriated one of Dapper’s designs in their 2017 Resort collection), with corporate leaders and inclusivity experts. The next month, the brand announced the $5 million Gucci Changemakers Impact Fund with grants for scholarships and U.S. nonprofits focused on creating opportunities in diverse communities.

The irony of all this is that Gucci might not have had to engage with issues of race, had the offending sweater not surfaced on American social media. Like many designers, Michele was not notably inclusive on his runway in the years 2015 through 2018. Today though, compared to many European brands, Gucci looks proactive. More important are the downstream effects: the fund recently announced the first round of scholarship winners. Gucci can potentially discover new talent, but it also brings attention to fashion programs at historically Black colleges, like Howard and Spelman, which some of the winners attend.

Michele admits that all of this was an accident: “It’s something that happened because I was ignorant. I didn’t know. But there is always a time to learn, and I learned a lot. I feel myself really on another land after that episode. We are getting so much energy, and we are sharing so much with everybody. I want to say thank God that it happened. We know more than we knew before.” He didn’t not know, for instance, about the existence of the Black colleges. And now other European designers do as well.

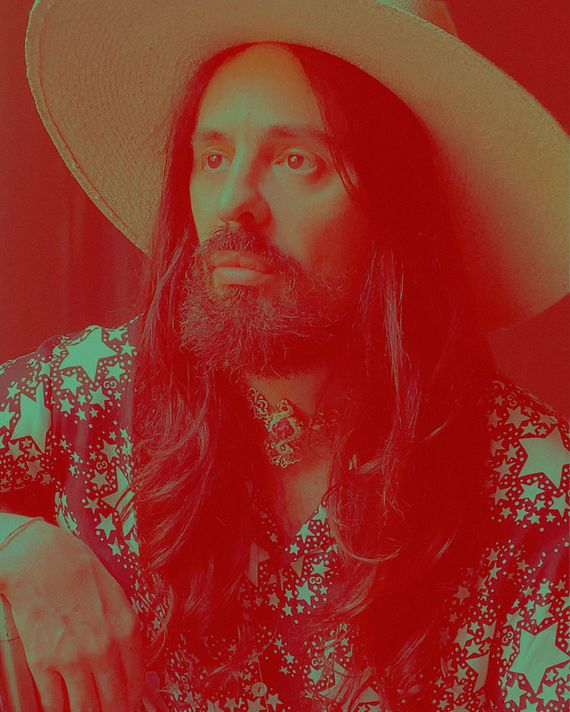

He is reflective on his run so far, “I did a lot of beautiful things. I really had fun. I felt like a little kid in the middle of the best years on Earth.” He mentioned he’d been doing a lot of crochet while staying in his home. He was wearing a light-blue shirt and his hair in two thick braids. Behind him was a large green-hued painting. He told me about his Umbrian property consisting of 400 acres. The oldest tower of the house dated from A.D. 800, and the place needed a lot of restoration. Later he sent me some photos of the eccentric compound of dark-stone buildings, including a long barn, set amid open, uncultivated landscape — as enchanting as a childhood fairy-tale.

*A version of this article appears in the August 31, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!

More From This Series

- Miuccia Prada Is Too Wise for Post-Pandemic Predictions

- Stella McCartney Might Not Recognize You Anymore

- Reed Krakoff Is Looking for a New Design Language