Angela Davis once said, “Prisons do not disappear social problems, they disappear human beings.” MoMA PS1’s new exhibition (their first since reopening to the public), “Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration,” began as a way for curator Nicole R. Fleetwood to process her own grief over the mass disappearance of relatives, neighbors, and childhood friends into the prison system. The exhibition follows the release of Fleetwood’s book of the same name and features works by 35 artists, both in prison and non-incarcerated. The works of art on display, which comprise only a portion of the vast collection that Dr. Fleetwood archives and explores in her book, are the products of a decade of painstaking research and relationship-building — and a commitment to make visible the humanity, talent, and resilience of the countless artists that are entrenched in or affected by the the U.S. prison system. Each piece in the show captures and preserves an individual viewpoint and experience and, in doing so, resists mass incarceration’s ultimate aim: to erase and disenfranchise.

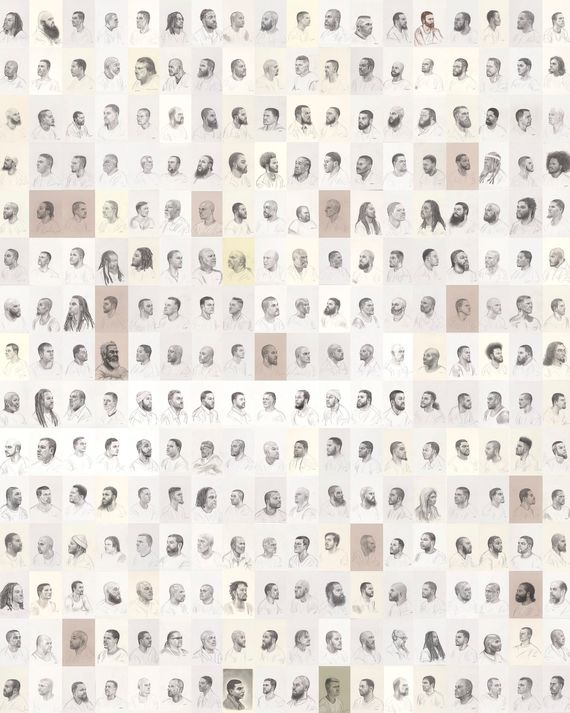

Face-masked, hand-sanitized, and socially distanced visitors are greeted by, fittingly, a series of works reflecting the havoc that the coronavirus has wreaked on prisons — where the transmission rate is five times higher than it is outside. Artist Mark Loughney, who routinely makes serialized portraits of his incarcerated peers with only paper and a graphite pencil, continued creating while in “lockdown” in the prison system. A new series of 40 images depicts men wearing PPE.

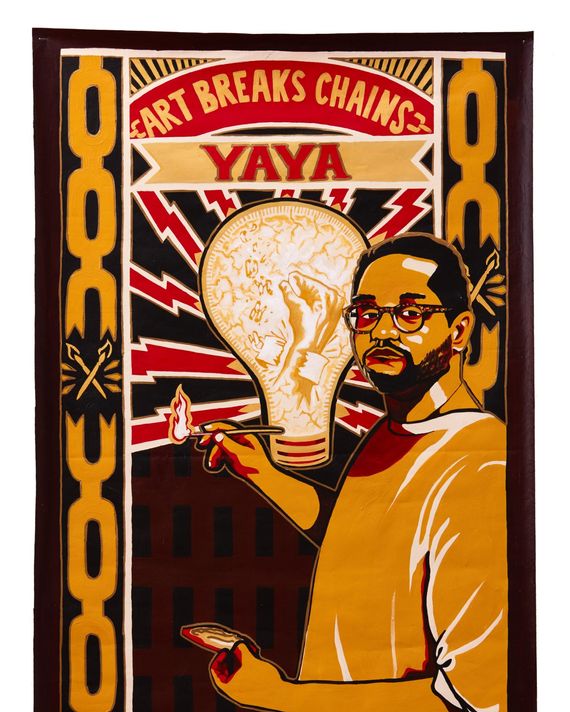

The pieces on display represent a mere fraction of the millions of paintings, drawings, sculptures, greeting cards, collages, and other visual material that are created under carceral conditions each year. “Given how large our system of mass incarceration is, there is no way we can think of art made under captivity as somehow marginal,” Fleetwood said. “It is a massive force and one of the most voluminous ways that contemporary art is made. It just circulates outside of established art circles.” Fleetwood describes the stakes of creative practice in prison in her book: “To make art in prison is to create under the conditions of scarcity of resources, lack of control over one’s environment, immobility, constant surveillance, and a combination of sensory deprivation and sensory overload, depending on where one is housed.”

Not everything in “Marking Time” was produced in prison. In a video triptych created after her release, Mary Enoch Elizabeth Baxter (stage name: Isis the Saviour) reenacts the most traumatic moment of her time in the system: the 48 hours she spent shackled while in labor, and, later, being separated from her newborn son. “Creating art about prison has not only allowed me to process parallels between my personal experiences with incarceration and systemic racism but also to connect my work to the collective subjugation of Black people in America and the diaspora,” Baxter said. The video is titled “Ain’t I A Woman” in honor of Sojourner Truth’s 1851 speech at the Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio. It confronts the enduring damage that mass incarceration inflicts on families — damage that feeds the cyclical nature of the system, which Baxter describes as “a womb-to-prison pipeline.”

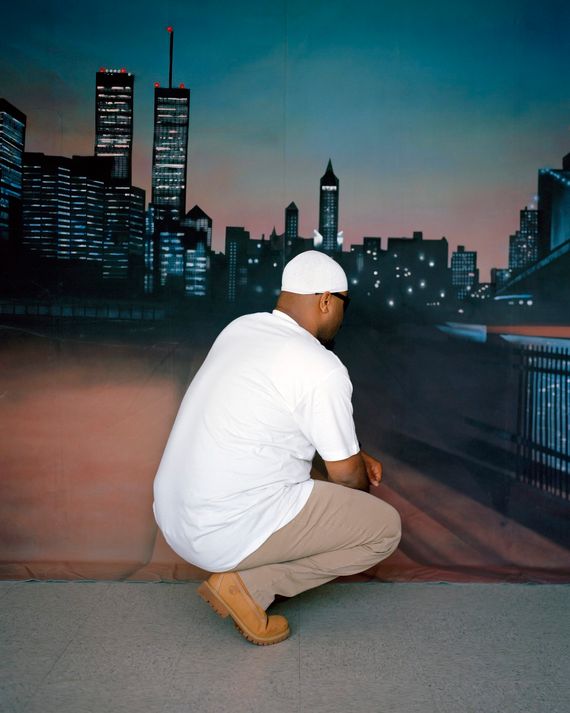

Fleetwood has had to overcome a decade of obstacles to find, acquire, and display the works in “Marking Time,” including a frustrating search to find a home for the exhibition. “I sent the proposal to several museums. PS1 was the only one that was willing to take a chance on it,” she said. Artist Mark Loughney commented, in a message relayed to Fleetwood on behalf of himself and other incarcerated artists in the show: “Having a giant truck pull and haul our work off to an important New York museum was the highlight of our career. ‘Marking Time’ will have its time, and when it does, the world will be eager to get out and experience as much life as possible, with renewed vision.” Keep scrolling to see more selections from the exhibition, as well as installation shots.

Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration is at MoMA PS1 through April 4, 2021.