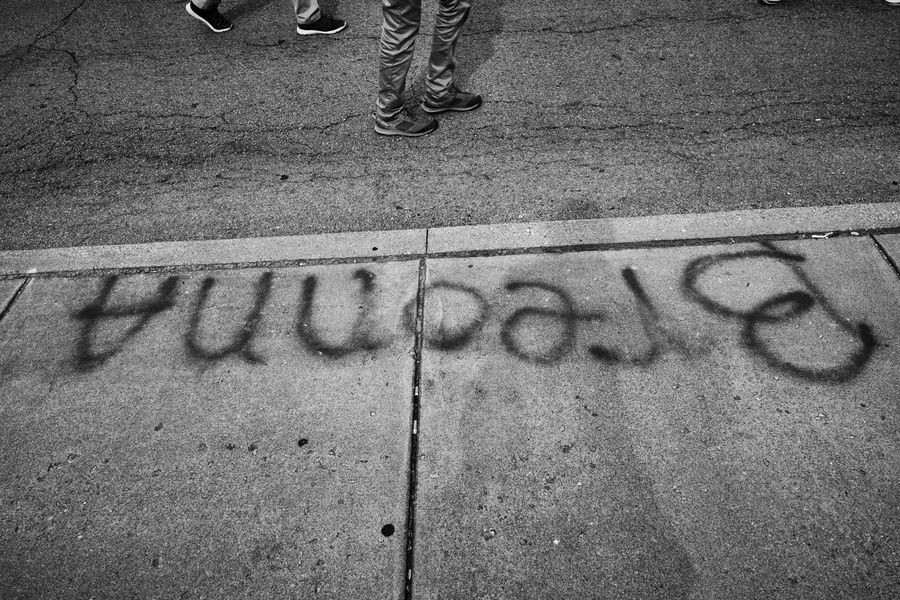

On Wednesday afternoon, when a Kentucky grand jury announced its decision regarding Breonna Taylor’s killers, photographer J.D. Barnes was watching with a crowd in Louisville’s Jefferson Square Park. “You heard audible gasps,” Barnes said. “It was just disbelief.”

More than six months after a trio of plainclothes Louisville police officers battered down Taylor’s apartment door as she slept, jurors decided to charge only one of those cops — but not for Taylor’s death. Instead, they indicted former officer Brett Hankison on three charges of wanton endangerment, a class D felony encompassing behavior that evinces “extreme indifference to the value of human life.” Hankison received one count for each of Taylor’s white neighbors, whose window he shattered with his gunfire. None of them were injured, and yet the indictment identifies them by their initials. Taylor’s initials aren’t acknowledged at all.

For many in Louisville, and around the country, it is a decision utterly devoid of justice — no more sense in the verdict than in the death. “It was as if they said he was completely innocent,” Barnes said. “What they indicted him on was nothing.”

Quickly, though, disbelief “gave way to a lot of tears, visible anguish, and that bled into a lot of anger,” said Barnes, who went to Louisville to document the aftermath of the announcement and spent the next several days and nights doing so. For more than a third of the year, protesters have tried to remain peaceful in the face of combative law enforcement. They have “tried to do things relatively the right way,” Barnes explained, “and at this point, there’s a lot of people who just don’t give two shits about it anymore, about doing things the right way.”

It’s not as if the Louisville Police Department did things the right way. Initially, officers classified Taylor as a suspect in a drug investigation, although it has since become clear that her involvement in the case was tertiary at best. Taylor had no drugs in her apartment; police subsequently admitted that they expected “no threat” from her on the night of the shooting, because they knew where their suspect — an ex of Taylor’s with whom she maintained a “passive” friendship — would be. A separate team of officers had already taken him into custody ten miles away, while the LPD’s “soft target” lay dying on her carpet.

“If you’ve ever had a loved one die, you know how it feels,” Barnes said, describing the outrage and pain as protests flared on Wednesday and Thursday nights. “Take that to a loved one being killed, then a loved one being killed by the very people who are supposed to protect and serve, and then the people who are supposed to show oversight for them ruling that it was justified. It’s just heartbreak after heartbreak after heartbreak, to the point where you’re going to start getting a lot of heartless people.”

Even before the grand jury delivered its decision, Louisville mayor Greg Fischer declared a state of emergency, “due to the potential for civil unrest” — a signal to some that, once again, police would go unpunished for taking a Black life. For two nights, Barnes said, activist leadership has “shown remarkable restraint in the face of police pressure,” from cops armed with flashbang devices and batons, and National Guard troops in BearCat vehicles. Authorities made at least 127 arrests on Wednesday, while officers reportedly formed a barrier outside a church offering to shelter demonstrators out past curfew on Thursday. Because Kentucky is an open-carry state, both protesters and counterprotesters are carrying guns. Barnes found himself a block away when two police officers were shot on Wednesday night. (They are expected to survive.) For Louisville, Barnes said, “it’s deeply personal.”

“Breonna Taylor was from here and she died here,” he continued. “The rest of the country has picked up on the story and they ride for Breonna Taylor, she’s become one of the rallying cries for this entire movement, but this is Breonna Taylor’s home. People knew her, people know her family.” The crowds span “people probably fresh out of their teens” to “older, distinguished women,” Barnes said. “These are everyday people doing what they must do.”

Below, see Barnes’s photos from Louisville.