Just about everything in the Hermès show could be read as a response to the predicament of the world — those of us who are still unable to travel freely or get close to people. The minimalist collection of poplin shirts and matching trousers, the plain coats in linen and suede, the jaunty A-line skirts, all suggest freedom of movement, while the amount of exposed skin — keyhole-back bodysuits, bandeaus worn under suit jackets, a shift made from latched strips of black leather — all seemed to invite a human impulse. Touch me.

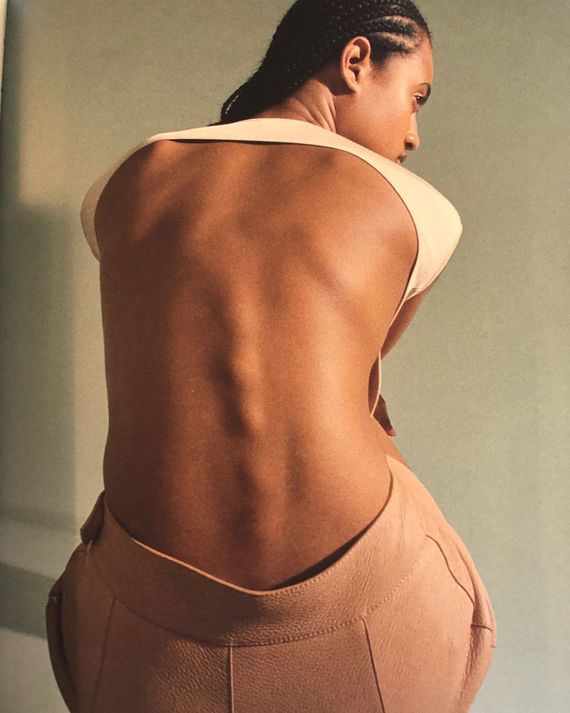

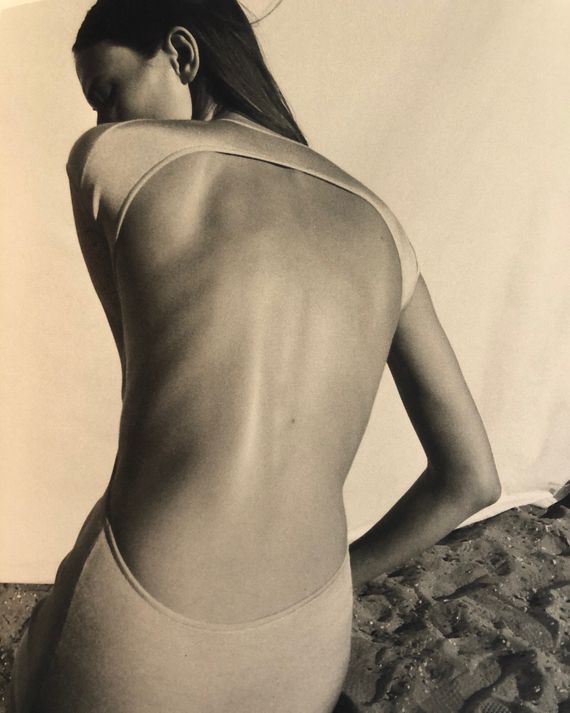

But there’s much more to this remarkable collection, by Nadège Vanhee-Cybulski, than that. She has also balanced tradition and modernity. The bodysuits, in stretch silk, expose most of the back. Looking at photographs from the scrapbook she made — for those who could not be in Paris for the live show this past Saturday — the link to modern sculpture is clear. The latticelike shifts, with a knitted under layer, are her version of fishnet, but the construction is pure Hermès: Each leather segment is held together by an X-shape silver piece typically used for buttons or jewelry. The poplin shirts and slightly high-waisted trousers, in light blue and poppy red, are summer classics. Less obvious is the belt of the same poplin, that Vanhee-Cybulski has thoughtfully added to the pants, to emphasize the waist.

And everything was shown with clogs, a shoe less associated with luxury than with comfort and support. “I have a strong memory of clogs,” said Vanhee-Cybulski, when I spoke to her on Friday on FaceTime. She was in the Hermès studio, doing the last fittings. “It’s really an outdoor shoe, something to wear between the house and the garden. It’s definitely the summer.” There was something almost cheeky about the pairing of humble, nonchalant clogs, with finer fabrics.

Vanhee-Cybulsi agreed that it was her most minimalist collection for Hermès. “Absolutely,” she said, adding, “It’s the woman I always think of. She’s strong, confident, and there’s a lot of skin.” The designer, who started her career with Martin Margiela and then worked at Celine with Phoebe Philo and later at the Row in New York, said, “I was very inspired by American women. They have this sense of fashion and at the same time a natural elegance. I took this with me.”

She told me that the colors of the collection, in particular the tans and clays and oranges with loads of black and dark brown, were based on the work of Magdalene Odundo, a Kenya-born British ceramist. When I asked about the rolled collars on some of the suede or leather coats, she unfurled one, the leather spreading over the shoulders like a scarf. Later, she pointed out some dresses inspired by the shape of aprons, saying, “They carry so much history,” before adding, with a laugh, “It’s also very difficult to make an apron look sophisticated.”

It’s also very difficult, I might have said, to create desire in timeless styles like crewnecks and A-line skirts, but that’s just what Vanhee-Cybulski has done. What is even more appealing is that, unlike other leading designers, she is beyond a discussion of what’s fashionable or cool. She’s about form and movement, and the freedom to trust her instincts. More and more, that’s a rare combo in fashion.