All in the Family is a series on kith and kin during a year like no other.

I was missing my luggage and my mother. It was 2013, my first time in Uganda, and she was trailing me by a few days after a canceled flight out of Kansas threw off our plans to visit her childhood home together. I stood alone in the airport, in a place that was totally foreign to me and looked out on a room full of strangers, feeling childish in my fear. I saw one man among the strangers who had a smile that looked just like mine. Was he my family? We opened our arms to each other and introduced ourselves. I was 23, doing everything for the first time, including learning how to be one person in an expanding family.

Is that a lesson that ever really concludes? This year, the pandemic reminded me of what my mother showed me about family, and how big the world can feel if you let it.

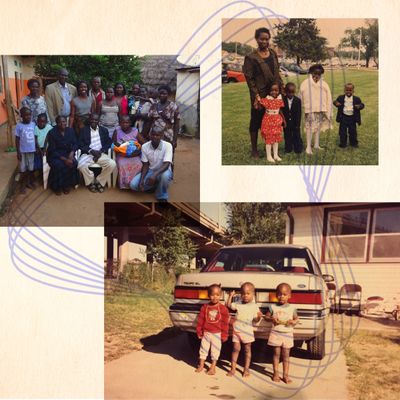

When my mother finally arrived in Entebbe, it was only her second time back since leaving in 1988. She immigrated to the States with my father, my half-siblings, my sister, and my twin brothers in utero. Before I was born, my family settled in Kansas, sponsored by my father’s relatives who had moved there first and who were never more than an hour away from us during my childhood. We visited them often then, spending all day at their house, the adults speaking animatedly in Luo, their first language, and us little kids following the older ones around, luxuriating in the novelty of our extended family. We were so isolated in Kansas, such a small network of people landlocked and alone in our culture in our adopted rural white towns. When we were together, it felt like we were gigantic.

The trip to Uganda was the first time I traveled with my mother as an adult. On my first days there by myself, I met my mother’s oldest sister and her daughters and sons and their daughters and sons. They spoke in Luo and were shocked that I couldn’t understand them. When we were little, my siblings and I didn’t know how to say anything in Luo except “hello” and “how are you?” My mother didn’t have time to teach us, so we spoke our one language and she was our translator.

With my family in Uganda, I felt half in and half out of every conversation. Then my mother arrived and the whole world seemed wide open again like when I was a kid. I could see and experience our gigantic world with and through her.

I left after a couple weeks and my cousins and I kept in touch via emails and WhatsApp messages to each other where we talked about nothing until later when my uncle died, and we became a phone tree of grief. Soon after that, much sooner than any of us could have expected, my mother died, then my sister, too.

In the years since, I’ve become a sort of expert in loss and tragedy: I know it when I see it, and there’s more of it all the time. I know how the world can tilt and shift and I have learned how best to hold on. I have suddenly become fluent in my second language of grief, an unexpected new and old language.

We buried our mother next to her mother, in the flowers she had shown me on our trip years before. At her funeral, I met people I didn’t know, people connected to my family by blood and by promises. I was less interested in being gigantic then; I was a girl alone who mostly just wanted her mother. My father buried my sister with his family, away from our mother, in a process that felt cruel and political in the way that tradition and family drama can be.

Back at home in California, I received what felt like an endless influx of messages from family members I half-knew, had only met once, or who suddenly wanted to know me. I felt bad, in the emotional sense, and also in the mean way. I couldn’t tell the difference between people who wanted to be close enough to wish me well and people who were just curious about what tragedy and drama looked like up close. I stopped picking up the phone.

In the span of two years, I had lost nearly half of my immediate family, including the person who translated the world for me. Every message, every conversation, reminded me that I was navigating the world without my mother. I refused to read whatever messages came through. I accepted the narrowing of our familial world again and then again.

And then it was 2020 and I was home alone. The scope of my world had narrowed to a few hundred square feet in Oakland. I had spent the past few years fascinated by things you can only know in retrospect, obsessed with last looks, last times, last everything. My list of lasts only ever got longer: the last time I hugged my sister, my last meal with my mother, group chats gone silent, messages ignored.

It felt dumb, unnecessarily painful, in the midst of a pandemic to keep my world small when I knew how gigantic it could be. It felt nearsighted to cut myself off from people when I knew, intimately, the unexpected way that death can sweep through a family, devastating so many so quickly in its wake. If I’ve only learned one thing in the past few years — and, hey, maybe I have only learned one thing in the past few years — it’s that you rarely if ever get to decide when anything ends, you only get to deal with it in retrospect. If you’re lucky, you might get a warning before the end.

I opened WhatsApp this year in March for the first time since 2018. I read the messages I had missed, and I had to laugh because it was nothing scary, nothing that I couldn’t read on my own. The messages contain the only Luo words I know translated into English: “Hello, how are you?”

I scrolled past message after message and read every single one. I clicked on the tiny profile pictures, zooming in close enough to recognize my brother’s high foreheads, my mother’s cheekbones in so many faces.

I told them how I am — I still tell them how I am — and then, in Luo, in the language of our family, I ask: How are you?

More From This Series

- Untangling the Secrets of a Teenage Mother

- Are There Nightclubs in Heaven?

- Nonmonogamous in Theory, Monogamous in Reality