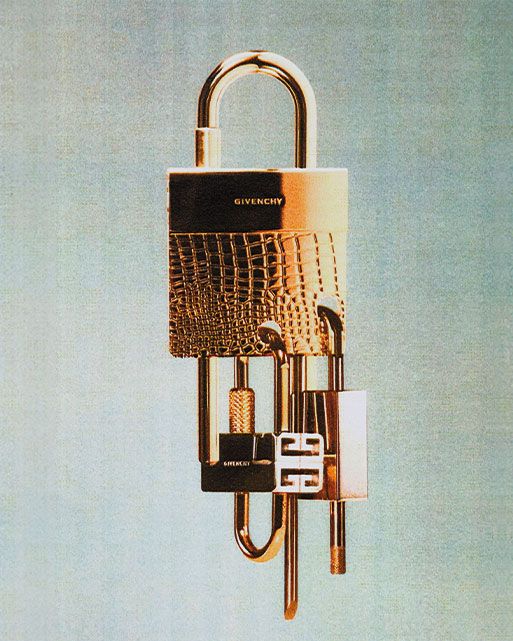

The lock’s the thing. That’s the hope, that’s the plan. When Matthew M. Williams teased the first look at his new vision for Givenchy, that’s where he began: His first ad campaign, shot by Nick Knight and released last month, skipped clothes altogether and went straight for hardware: giant, worshipful shots of a new Givenchy lock, a new Givenchy chain-link. Williams is a hardware nut — at Alyx (full name 1017 Alyx 9SM, but try saying that out loud), the label he founded in 2015 and continues to run, he turned a buckle, based off a Six Flags roller-coaster safety-strap fastener, into a totem. It was a bold move, but it worked. “I think it’s a great foundation to start from,” he said of hardware on a video call this past weekend. The locks, he said, are a symbol of love and connectedness, the way they are on the Pont des Arts in Paris, where lovers attach them to the bridge’s grate and then toss the key into the Seine below. And a symbol, he added, of “my commitment to Givenchy.”

Locks — which can be hung off bags, turned into jewelry, used to dress up old items and spiff up new ones — are an accessory’s accessory, and there’s something savvy about starting there: Like almost every luxury fashion company, Givenchy keeps the lights on with accessories. There’s a reason that the new look-book images — shot by art photographer Heji Shin, whom you may know from last year’s Whitney Biennial, in lieu of a runway show — are so insistently bag-first. Williams tweaked existing successes, like the Antigona, and introduced a few styles of his own, like the swoopy new Cut-out bag (no relation). Then there are the accessories-for-Instagram (the Fiji Water–bottle–shaped flasks), the megachain jewelry, and everywhere — dangling off belts, closing jackets — those locks. Williams is betting you’ll see a lock and think, Givenchy — like a new kind of logo. That’s not a bad idea, because the Givenchy logo doesn’t carry as much weight as those of many of its peers. It doesn’t even own the G, really — Gucci does, ever since Tom Ford shaved one into a model’s pubic hair, at least.

That’s a challenge for Givenchy across the board. For all the rhapsodizing that goes on about “brand DNA,” the Givenchy look has never been as clearly defined as some of its contemporaries. Alexander McQueen, who designed for the house in the ’90s, once told my colleague Cathy Horyn that he “didn’t think the house was even worth keeping open since it did not have a signature style, like Chanel’s cardigan jacket or Dior’s romance, that it could endlessly exploit.” It was a way station on the road to greater success for enfants terribles McQueen and his predecessor, John Galliano. When one thinks of Hubert de Givenchy, its aristocratic founder, it’s generally for his ongoing collaboration with Audrey Hepburn and the glamour of Hollywood. But that’s a world away from the Givenchy of Riccardo Tisci, who defined the label for a generation with a snarling, dark streetwear edge; there are those of us who will never forget seeing those Rottweiler T-shirts. (I won’t forget them, in part because we sat in the dark, in the cold, in Paris’s Palais Omnisports de Paris-Bercy, waiting over an hour for the show to start, thanks to a power outage of some sort. Memories!) Clare Waight Keller, who ran the house for three years after his departure, designed some of its most breathtaking couture (including Meghan Markle’s wedding gown) but didn’t plug into pop culture in the same sparky way that made Tisci’s Givenchy feel like a uniform for the Zeitgeist. By then, Givenchy himself was long retired and devoted to his collection of 17th- and 18th-century sculpture. He died in 2018.

Williams, in other words, has plenty to draw from. “I think especially when arriving at a house that has so much history, for me, it’s about reinterpreting the things about Givenchy that I’ve loved and liked in the past, and interpreting them in my own way,” he told me. There are references like Easter eggs scattered throughout — the horn heel of a shoe, which calls to mind the sheep horns McQueen used in a famous couture collection from 1997, or the “glove sleeve” on a top with shades of Hubert and Hepburn’s gloves. The presence of Tisci seems to loom large — Williams, who turns 35 this month, came of age in the Tisci era — but so too do the spirits of Margiela, Jil Sander, Rick Owens, and designers of more recent vintage. There are nice pieces scattered throughout — you could see a musician warming to the sharp tailoring or one of the oversize leather jackets, and Williams, who in the past has worked with Lady Gaga and Kanye West, all but promised that you soon will — but what’s missing from this maiden voyage is a strong statement about what Givenchy stands for now. Some of the styling seems like empty provocation — how many leather undies for men does one need to show before the point is made? And some bits seem silly and throwaway, like the Devil-horn caps or the odd three-toed socks and sandals, though novelty items do sometimes take on a life of their own in the market. Stranger things have happened.

I looked through the collection, on the call and then onscreen, and came back to the lock — that’s what sticks. No one builds a new vocabulary in a season, but it’s likelier to start there than more pool-slide sandals or treated denim. It’s a small detail, a commitment, a building block. From there, Givenchy could grow.