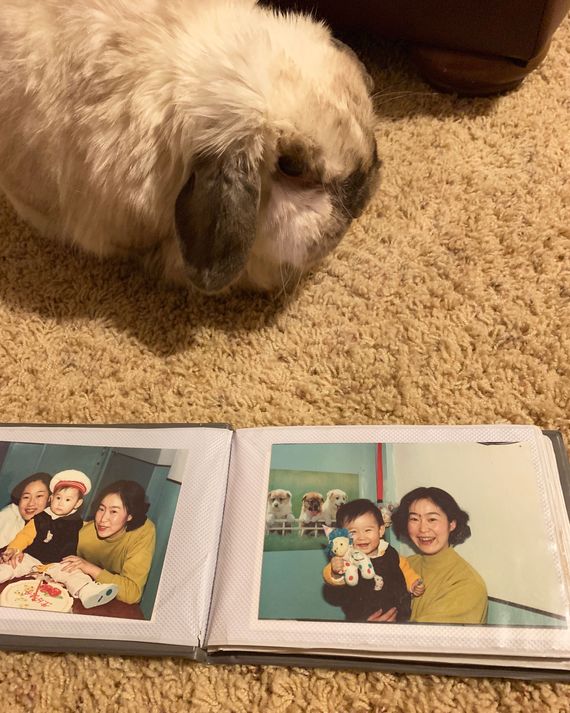

I brought Penny home the summer before my senior year of high school. She was a month old, all fur and flop in gray and white. Gray nose, long gray ears drooped over the sides of a white little face with translucent whiskers, a gray pom-pom of a tail.

My parents weren’t happy about my new pet bunny at all, but they welcomed her under the agreement that I would be the one to feed her, litter-train her, and bring her with me to college the next fall. None of this happened.

Instead, they fell in love with her. For ten years, they fed her the best and freshest vegetables from their garden, groomed her, doted on her, and, when she got too sick to use the litter box, covered an entire corner of the family room with cardboard and paper so that she could still roam around — a bunny forever at large. She was our family pet, but she was also what allowed me to see my relationship with my parents in a whole new light.

Our tiny town was in the prime of coal country, 50 miles north of Pittsburgh, and we were one of three nonwhite families. My parents had moved us from China to the States when I was 8 years old. They loved Penny in a way that surprised me.

Growing up, I saw my friends’ parents give them dating advice, allowances, and unsolicited hugs. They screamed “Love you!” out the windows of their cars after dropping them off at school. My parents were not so affectionate. That’s often the case within Chinese families like mine, members of which, as decreed by Confucius, must prioritize hierarchy, obedience, and fulfilling one’s duties. Children must obey their parents, and parents must deliver on their duty to take care of their children. Demonstrations of affection are irrelevant. Hugs and the words “I love you” come few and far between — a cultural phenomenon that’s difficult to reconcile with Western standards, something that confused me to no end when I was a kid.

It wasn’t until I was in my 20s that my mom began wanting to hug me whenever I came home. American culture was rubbing off on her, I suppose, and the scarcity of my company might have made a difference. My dad still doesn’t hug that much. We still don’t like to talk about feelings. And when they say they love me, it’s never in Mandarin. Never wo ai ni. Always, “Okay, don’t stay out late, love you, bye!”

Before Penny came along, we’d never had a pet. We fought a lot. I couldn’t make sense of why they weren’t like everyone else’s parents. Why even when I brought home straight A’s or got my own column in the school paper as a freshman, they were unfazed. They never bought me flowers when I performed in school plays, or even to my piano recitals. Instead, they pushed me to study harder, they reminded me I was forbidden from dating, perpetually warning me that if I didn’t prioritize my academic performance over everything else, my future would be ruined.

It wasn’t just the rules. My parents were different. They ate spaghetti with chopsticks and they liked to slurp. They made everyone wear slippers in the kitchen because “the tiles are cold.” They drank only hot water. They forgot my friends’ names. They still don’t eat out in restaurants because they think it’s a waste of money. And I resented them. Their strict rules and differences were a constant reminder that I too was different.

With Penny, my parents were so affectionate. Nuzzles here. Headbutts there. A little squeeze while holding her in a towel to clip her nails. They called her Pan Pan, per the Chinese locution of repeating syllables in one’s name as a nickname.

Last year, as New York emptied out, my boyfriend and I left to stay with my parents in my hometown. There, Penny mostly confined herself to her couch corner. She had lost some of her teeth, and so my mom would run her pellet food under water, making it softer to chew. Still, she was nuzzly when she wanted snacks and attention, and feisty when anyone tried to pick her up.

One Sunday morning, my mom found Penny fallen on the path to her litter box and unable to get up. We thought she was dying. We laid her in her corner and fed her pieces of banana. I wept. The prognosis wasn’t good. A vet told us that it could be an ear infection, or it could just be her time.

But against the odds, Penny got better. I was grateful, but not entirely at ease — living with my parents again was bringing up memories of the past, memories that went beyond the bunny we all loved. The loneliness of being a Chinese girl in coal country, pretending to like Radiohead so the boy I liked would like me back, pushing my straitlaced parents away because they were so foreign to what I saw around me. They didn’t know what it was like to grow up different from everyone else. They couldn’t. And I wasn’t sure if I could forgive them for that.

With me under their roof again, my parents were as chiding as ever: my mom nitpicking my every conduct, my dad scolding us for wasting food and letting the faucet run too long. We had regressed to the versions of ourselves ten years ago: Dinner was at 6:30 p.m. sharp every day. Everyone had an assigned mug. Slippers were mandatory in the kitchen. No shoes allowed by the porch door. Penny, all the while, remained the center of attention. Mom called her sheng xian tu — our little angel bunny.

At the end of May, my boyfriend and I decided to return to New York. We woke up at 6 a.m. to leave on a Sunday. My parents were up too, and they helped us pack the car, pushing fruits and meats and Costco-brand yogurt on us to take on the journey. “You’ll get hungry,” my mom said, handing me a gallon bag of tea eggs.

Heading back upstairs once more to grab my phone charger, I found Penny in her corner. I fed her a peanut and gave her one last nuzzle. She smelled like my mom’s hand lotion. In the driveway, Mom and Dad lingered. I said good-bye, crouching into the passenger seat, not wanting anyone to see that I was crying.

It was the longest I had been home in a decade. In my parents, I saw subtle things that I hadn’t before: new lines on their faces, tufts of black hair now gray, how stubborn they are in their ways still. I wondered if I had been harsh on them as a kid. Too quick to write them off, too flippant in saying terrible things about them when I complained to my friends. Had I taken them for granted? Do I still?

For nearly all of my childhood in the States, I wished for a different family. I wished to be normal, which was abstractly everything that my household wasn’t. But this past spring, spending time with my parents and our beloved Penny finally let me accept that we never had to be “normal.” We don’t need the word love. And my parents never needed to give out hugs. Instead, they push food, and they save the best parts for me: the fattiest pieces of roast duck, the most golden pears from their pear tree. My parents, who, despite their tepid embrace of physical affection, had so much love for Penny. I get choked up sometimes thinking about how they cherished her. Because if they had that much love for a tiny critter of prey that ate her own poop, I can’t even fathom the love they have for me.

Back in New York, in my tiny apartment, I attempted to make my mom’s recipe for chicken wings. I showed my roommate the bag of garlic that I brought home from the garden, and we both marveled at how fresh it looked, how pert. I went too heavy on the garlic, but texted a photo to my mom anyway. She sent me back a photo of Penny.