On a late September evening in 2020, the audacious and largely senseless sparring of two president hopefuls was interrupted for just a moment. Democratic nominee Joe Biden turned toward the camera to address the audience directly, and spoke of his son Hunter Biden. “My son, like a lot of people you know at home, had a drug problem. He fixed it, he’s worked on it. And I’m proud of him. I’m proud of my son.”

Even the most politically cynical viewer could have found the moment heartwarming. Despite myself, tears may have briefly welled in the corners of my eyes. To stand by someone through severe addiction takes patience and love without conditions, something that many parents just aren’t capable of giving. Mine sure weren’t.

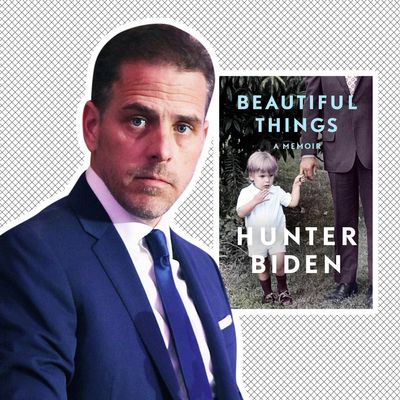

Eight months after that debate-stage moment, as the right-wing attacks have settled significantly, Hunter has emerged to tell his side of the story. With the memoir Beautiful Things, he presents his response to the stigmatization and derision he’s faced on a massive public scale over the last couple of years. He describes the terrible losses he’s endured through his life: how he and his brother, Beau, survived a car accident that killed their sister and mother; how decades later he lost his beloved brother to cancer. Much of the book is concerned with the time following Beau’s death in 2015, and what Hunter describes as intensifying periods of addiction punctuated by ever-briefer periods of rehabilitation.

It’s impossible not to extend empathy toward Hunter while reading of the tolls of his destructive patterns of substance abuse. The difficulty with Beautiful Things is that it refuses to extend that empathy to others caught in the grips of addiction. Throughout the memoir, Hunter doesn’t attempt to interrogate or vanquish the “sordidness” associated with drug use and addiction. He instead invites the reader to ogle at those trapped in poverty and addiction — people he knew — like animals in a zoo. The people within “the darkest corners of every community … the lowest rung of the [criminal] subculture,” as Hunter calls them.

The people of what Hunter describes as “an opaque, sinister night world” aren’t given histories, characterizations, emotions, or personas. They’re the non-playable characters of Hunter’s addiction saga, slapped with stereotyping labels and left to circulate robotically within their programmed roles as ne’er-do-wells. Hunter recalls them with revulsion, admitting to being ashamed that he had considered them his friends — despite recounting how they frequently looked out for his best interests. Among the dozens of other addicts that inhabit the pages of his memoir, only one is allocated some form of personhood and written in a way that holds space for her own struggles and suffering. Using the pseudonym Rhea, Hunter describes a caring and deeply funny woman swept up by the crack-cocaine epidemic whose long-term precariousness has left her both mentally anguished and full of wit and empathy.

Unflinching portrayals of marginalized and disenfranchised people afflicted by addiction and poverty aren’t all that unusual for books of this genre. Constructing a narrative of drug use, precarity, and crime that’s unconcerned with politeness is central to the literary genre of the addiction narrative, a tradition whose constituents range from William Burroughs’s Junkie (1953) to Nico Walker’s Cherry (2018). These texts can range from straightforward memoirs to autofiction, but are united in how they use the writer’s lived experiences to tell a story of addiction. Hunter hints at his attempted alignment with this literary history early in the book, with a brief and somewhat ominous reference to Charles Bukowski’s Post Office (1971). The other authors who write within this category speak casually about their interactions with criminals, sex workers, and people experiencing houselessness, and would probably agree with Hunter’s framing of them as “misfits and outcasts.”

But the distinction is that those authors write about that world from within it, while Hunter describes it while sitting slightly above it. Regardless of the benders he partook in with those misfits and outcasts, or the pipes and scouring pads he shared with them, he wasn’t ever really part of their world. That’s not to say that privilege keeps the possibility of substance use out of the picture entirely. Another prominent political figure, Cindy McCain, will touch on her own struggles with addiction in her upcoming memoir, Stronger. Given that her socioeconomic standing is similar to Hunter’s, it’ll be interesting to see how she positions her experiences and where she places herself in relation to other communities of addicts. For Hunter, there was always an impenetrable buffer between him and them. A barrier composed of wealth and prestige, that kept Hunter shielded from many of the harms of addiction.

Hunter would disagree with the notion that he floated above the world he writes about, and he does so vigorously throughout the memoir. He groups himself with addicts as a community in both content and style of speaking, littering his talk about addiction with “we” and “us.” He positions himself as a spokesperson imparting his supposed insider’s knowledge to his readers. Threaded through it all is the idea that addiction is some sort of equalizer — an experience that subordinates all other facets of identity and circumstance to create a class of its own. “[Other addicts’] circumstances may be different, their resources far fewer, but the pain, shame, and hopelessness of addiction are the same for everyone,” Hunter declares. “It doesn’t matter how much money you have … in the end, we all have to deal with [addiction] ourselves.” The problem is, that just isn’t true.

Like Hunter, I’ve spent time with a hot pipe against my lips, feeling the rush wash through me and catapult me into space. I’ve spent hours writhing in place, sweaty and volatile, unable to do anything but obsess over my craving. I’ve sabotaged my life repeatedly, helplessly, deliriously. When Hunter speaks of the scorchingly single-minded fixation on needing the drug, and then the simultaneous exhilaration and shame of giving in to the craving, my body alights with resonance. In those descriptions, he does tap into some kind of an addict universality. No matter who in the world you are, if you’ve been tethered to addiction, you’ll have been there with him.

But Hunter hasn’t always been there with us. He claims that “the most insidious thing about addiction … is waking up unable to see the best of yourself.” When I was immersed deeply, the most insidious thing was knowing that if I only had enough money for either drugs or food, I would choose the drugs. The most insidious thing was letting myself flake on another job because I wanted to get high instead, even though I had nothing in my bank account and needed the paycheck. Despite his dark foray into addiction, Hunter remains alienated from what’s really the most insidious part of being an addict: that it’s a financially impossible way to live, and yet millions around the world live that way anyway.

Coddled by the five-figures-a-month income he was receiving during the height of his addiction as a board executive for Burisma, Hunter never had to worry about securing housing or food. He could afford the lavish rehab centers and detox retreats. Most importantly, the next hit could always be purchased. For those deep in addiction, the physical and emotional need for drugs that they can’t afford causes all sorts of consequences, from houselessness to being forced to engage in survival sex work or drug selling. In Cherry, for example, Nico Walker describes how the protagonist’s heroin habit eventually led him to rob banks to finance his habit—Walker himself wrote the book from a jail cell, drawing on his own experiences. The people throughout Beautiful Things referred to as “hookers,” “gangbangers,” and “con artists” are all just trying to survive in the ways that are available to them, the same as Hunter. Except that the scope of what’s available to Hunter — a rich white man — is far larger.

On an emotional level, the parts of the memoir that describe Hunter’s experiences within disenfranchised communities function like poverty porn. Meaning, media that portrays the lives of the extremely poor in a way that’s meant to invoke sentiments of disgust, pity, and disbelief in the reader. Hunter’s memoir invites readers to gape at the depravity of the gun-wielding squatters of LA’s Tent City and gawk at the nefariousness of the shoeless crack dealers who con unsuspecting targets out of money.

What differentiates Beautiful Things from more banal pieces of poverty porn is that it purports an insider’s view. Thus, readers are exonerated of the nagging guilt that can arise when they treat the less fortunate like a spectacle. The memoir claims that its voice comes from within the communities it describes, so readers can indulge themselves without feeling as though they’re dehumanizing those people. It’s their own voices, so there’s no problem. Until you interrogate that a little closer.

Beautiful Things carries Hunter Biden out of the depths of addiction and into a happy ending. He manages to rid himself of crack, find love again, and rejoin his family as a stable and proud person. He once more surrounds himself with a consortium of powerful, wealthy people, leaving behind the squalor of cheap motels and trips through encampments. “I want those still living in the black hole of alcoholism and drug abuse to see themselves in my plight and then to take hope in my escape,” he says. Hope won’t provide people with the resources and support they need to live the lives they want to. It’s a beautiful thing, to have hope. But for all the millions of addicts who don’t have the means to think beyond the day-to-day of survival, beautiful things are more or less irrelevant.