In recent years, monuments have become a subject of fraught national debate. Across the country, whether around the removal of Confederate symbols and statues in the South or the creation of Black Lives Matter Plaza in D.C., citizens and elected officials are engaging in urgent conversations about public artworks, the stories they tell, and those they leave out.

“As a country, we are grappling with the meaning of monuments; we are questioning the way history lives in public spaces, and that questioning is really valuable,” says Paul Farber, the director of Monument Lab, a Philadelphia-based public-art studio. “But instead of investing too much in conflicts over demolition — which often get a lot of attention — we want to bring people together to envision the next generation of monuments in a way that feels more inclusive and hopeful.”

Monument Lab, which was co-founded by Farber and artist Ken Lum at the University of Pennsylvania in 2012, works with artists, activists, and community leaders in neighborhoods across the country to “cultivate and facilitate critical conversations around the past, present, and future of monuments.” It has organized dozens of public-art projects in cities from New Jersey to Los Angeles to Tennessee.

This past Saturday, the studio launched its most recent venture, an outdoor multimedia exhibition and program series hosted by the Village of Arts and Humanities in the historically Black Fairhill-Hartranft neighborhood of North Philly. Co-curated by Farber and former Monument Lab fellow Arielle Julia Brown, the show brings together a formidable group of artists — five of whom are Black women and several of whom are residents of the neighborhood — to create public works around the theme of “Staying Power.”

Speaking over Zoom last week from the site where several large murals were being installed, Farber described how the show, which was already in development prior to the pandemic, evolved. “It began with a virtual site visit, and Arielle and I gave all of the artists this prompt: What is your staying power in your neighborhood?”

The curators encouraged the artists to reflect on the stories and experiences that tie the community together — as well as the hardship it has endured. Fairhill-Hartranft is among Philadelphia’s most economically and socially vulnerable areas, with high rates of both poverty and violent crime. And, recently, the neighborhood has seen a wave of gentrification that has put pressure on longtime residents to leave. “These projects are personal acts of expression, of course,” says Farber, “but they are also rooted in history — in systemic problems. This project is a response to systemic racism, inequity, disinvestment, and police brutality that this community has endured for generations.”

While the word monument may conjure images of marble pedestals and bronze men on horseback, the work in “Staying Power” represents a far more expansive and interactive vision of what public monuments can be. Brown and Farber refer to the artists’ pieces as “prototype monuments,” emphasizing the experimental nature of the work. “We don’t have answers for what the future of monuments should look like,” says Farber, “but we have lots of questions. We want to let that curiosity guide us.”

The artists responded to the prompt in myriad ways — one created large-scale outdoor sculptures, another made a photographic installation, and another produced a series of live performances. “We define a monument broadly as a statement of power and presence in public,” Farber explains, “and that can take many forms. There were really no formal limitations on what they could do.”

“In my work as a dramaturge and also as a curator, I think a lot about what counts as radical for Black artists. As a Black person, just the act of existing in space, of being loud and embodied and moving down the street, can be radical,” Brown says. “This project encouraged all of us to think deeply about how to create monuments that embody Black radicalism and how history shapes the way we move through the world.”

While “Staying Power” is firmly grounded in the local community, the show’s themes resonate with conversations about public art taking place in neighborhoods across the U.S. Last fall, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation awarded Monument Lab a $4 million grant as the inaugural partner in its new Monuments Project, a five-year $250 million initiative that aims “to transform the way our country’s histories are told in public spaces.” With the grant, Monument Lab plans to open ten field offices in cities around the U.S. where they will partner with local artists, activists, and organizations to support similar local projects.

In all of its projects, Monument Lab works with local community leaders to organize (socially distanced) events and programming that aim to make the process as collaborative and inclusive as possible. “For us, the process is as important as the result,” says Farber. “We want to engage the community, connect people, and foster real collaboration so the residents themselves can be part of articulating their collective vision for their neighborhood’s future.”

We asked a few of the participating artists what the show’s theme, “Staying Power,” means to them. Below, their answers alongside images from the show.

“I am curious about the formation of the neighborhood — who stays, moves in and out; what objects are carried, what remains.”

Deborah Willis, photographer, historian, and educator.

I have thought about the notion of “staying,” about the transience of this country, how leaving is often synonymous with upward mobility, and those people that remain, that stay behind. This is particularly evident in Black communities where this American tug-of-war between community and mobility is exacerbated, where the “price of the ticket,” as James Baldwin wrote, for thriving Black communities was redlining, urban renewal, gentrification, and the perception of powerlessness. That’s precisely why the foundation of this exhibition has everything to do with the power of those who stayed and, in particular, Black women whose power has never been transient, has never left, always stayed because the basis of that power is love. Researching and photographing for “Staying Power” allowed me to reflect on joy, loss, love, and storytelling — certainly the continuum of my work. But if one does not understand that basis, that power, that permanence, then what one gets in terms of representation … a sidewalk altar in memoriam of a young Black woman killed in the neighborhood, a group of women that worked their craft from their “heart and mind” because they worked jobs outside of the nine to five spectrum. Photographs of rowhouses include the interiority of women who reinvest in the Village community. I am curious about the formation of the neighborhood — who stays, moves in and out; what happens when one crosses state lines to seek a new life and opportunities? What objects are carried, what remains, what is sustained only through the experience of memory — dress, foodways, photographs, religious symbols, sounds!

“This work honors the unseen moments of everyday radicality and the fierce hospitality animating unassuming family homes across the country and across the decades.”

Sadie Barnette, visual artist.

It is hard to hold steady these days, but when I think of strength and power, I think of my family’s living room. The way we hold it down and protect and hold and behold each other in these common but sacred spaces is what I see as our greatest staying power. Love is the rock.

The living room has witnessed dance parties, sermons, the best debaters and orators, and held space for hospice, loss, grief, flowers, and meals. The room I’m remembering was in the home of my Aunt and Uncle in Compton, California. In 1954, Alvin and Margaret White moved across the country from West Medford, Massachusetts, and were the first Black family on the block. When I think of the arc of history that they lived, as Compton, and the world, changed, I think of all the big and small moments — the unforgettable and the mundane — unfolding right there in the parlor. Their door was always open to family.

From Oakland to Compton to Philadelphia, Black families create spaces of safety, warmth, and witness as the world outside continues to offer violence and never justice. At the invitation of Monument Lab and North Philly’s the Village of Arts and Humanities, I am constructing a glittering living-room scene in the 2558 Germantown Avenue storefront space. This work honors the unseen moments of everyday radicalness and the fierce hospitality animating unassuming family homes across the country and across the decades … from the magical matriarchy of my aunties to Ms. Nandi’s legendary living-room “candy shop.”

power looks like current and former residents reclaiming land, space, time, and memory in the neighborhood.”

Black Quantum Futurism, interdisciplinary art duo Camae Ayewa and Rasheedah Phillips.

Staying power for us is an act of reclamation. As the neighborhood undergoes rapid change over the next several years, an activation of staying power looks like current and former residents reclaiming land, space, time, and memory in the neighborhood — taking those things back from the forces that have displaced, erased, stripped away, or disconnected them from their homes and community.

“The installation highlights the struggles of the present while imagining the day when all women serving life are set free.”

Courtney Bowles and Mark Strandquist, activists working in collaboration with six women whose lives have been impacted by the criminal-justice system: Tamika Bell, Paulette Carrington, Starr Granger, Ivy Lenore Johnson, and Yvonne Newkirk.

When we consider the idea of staying power, we first ask, Who is missing? Who has been displaced? Who is fighting to help them return? In North Philadelphia, the extreme of displacement is being permanently removed through life imprisonment. There are 200 women serving life in Pennsylvania; 54 of them are from Philadelphia.

Our installation, On the Day They Come Home, is both a monument and a memorial. As a monument, the installation celebrates the resiliency and power of former long-term and life-sentenced women, and those with impacted family members, through larger-than-life portraits, poetry carved out of charred wood, and interactive audio portals that amplify the stories behind the sculpture. Around each woman’s portrait is a wreath of flowers that symbolizes a core tenet of the abolitionist world the women advocate for: healing, resistance, resiliency, counter-narratives, and love. The installation highlights the struggles of the present while imagining the day when all women serving life are set free. As a structure, the installation inverts the image of a prison chain gang by creating a circular and unified formation that hints at a crown to celebrate their power, and a stage to celebrate the future for which these women are fighting. Come through. Come see, listen, and dream with us.

“These monuments are places we can come to pay homage and to acknowledge the labor of women in response to violence. Through this labor, these women enact promise.”

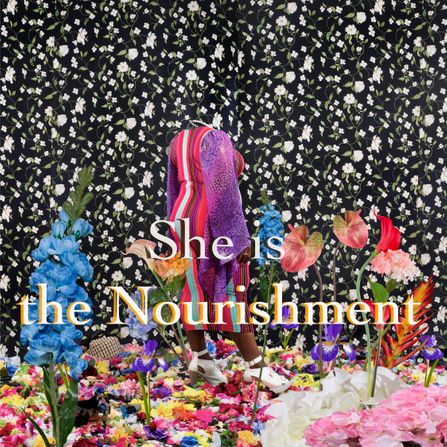

Ebony G. Patterson, visual artist and educator.

When I think of staying power, I think of the labor of women — the work and commitment made by women for their communities, the labor and care that happens in the in-betweens, that never gets noticed but nourishes a community so it can grow and flourish. These monuments are places we can come to pay homage and to acknowledge the labor of women in response to violence. Through this labor, these women enact promise.