Edward Enninful, the editor of British Vogue, was standing with the designer Nicolas Ghesquière near the head table at Louis Vuitton’s dinner for Frank Gehry on Monday, at the Fondation Louis Vuitton, the contemporary art center Gehry designed in the Bois de Boulogne that looks like a sailing ship. Or a flock of gulls come for a rest. Floating high above the tables — set with mounds of blue and white hydrangea and gleaming crystal — were giant paper clouds.

Well, why not? When you’re Frank Gehry and you have the resources of LVMH, you can conjure anything. The clouds were actually apropos of a new fragrance — rather, a series of perfumes — for which Gehry provided the bottle design, “Cosmic Cloud” being one. The scents are the work of Vuitton’s “nose,” Jacques Cavallier-Belletrud. He’d even supplied the tables with mini-atomizers of hand sanitizer infused with lavender grown near his home in Grasse.

It was all a little heady. The flowers, the delicious food and wine, not to mention the highly unusual fact that there were a mere 100 guests, including Florence Pugh and her mom. By the time Katy Perry, in a spangled dress, came out to sing, I was ready to smash my face in the dessert, something called Absolu chocolat et poire enveloppée délicatement.

After nearly 16 months of lockdowns, sweatpants, isolation, home cooking, and Zoom fatigue, I was ready for a little enveloppée. I asked Enninful how he felt about physical reentry into the fashion world and all its glittering satellites.

“Give me five minutes,” he said, and then, with a twinkle. “Well, a minute.”

Ordinarily, I don’t cover the Paris haute couture — that is, the made-to-measure collections produced by fewer than a dozen houses for the super-rich and discerning — although in recent years they’ve become an engine of creativity. But these shows mark the return of actual showings after the only pause since the German occupation during the Second World War, and I wanted to see how the couturiers and ateliers would respond.

Would there be more color, a release of pent-up energy? Paris has certainly reopened. The cafés are bustling. In the evenings, young people flock to the wide lawns near Les Invalides. “It’s like they’re erasing the memory of the bad time,” said the designer Giambattista Valli, whose tulle and silk confections are meant to span a night in Paris, through dawn, and have more than a touch of the erotic in them, with densely layered skirts sometimes splitting open at the pelvis and superbly done pantsuits in menswear silk married with long, hooded capes out of a Parisian bordello fantasy.

Or would the collections be more subdued and cautious, as if still in the shadows of a plague? That was the sense I got, partly, from Maria Grazia Chiuri’s chaste collection for Dior, with its many head-to-toe looks — riding-style hats, coats, full skirts, boots — in gray and brown tweeds, the tones of the North Sea coast. In contrast to Chiuri’s sublime January couture show, this one was stubbornly grounded, almost drained of fantasy. Even her many pleated goddess dresses refused to dazzle, although they were perfectly pretty.

Yet the show quietly imparted a virtue of an institution too often condemned as extravagant and shallow (as if there’s anything wrong with either quality in the context of self-presentation). Those tweeds were hand-loomed and often a subtle patchwork of textures. Lining the walls of the show space — a tent behind the Musée Rodin — was an embroidered mural, its panels done by a needlecraft school in Mumbai that Dior supports, based on an abstract landscape design by the artist Eva Jospin. After two full seasons of viewing clothes on screens, Chiuri was giving her small, socially distanced audience what they had been craving: a heavy dose of materiality. At the same time, she was celebrating the trades that are the essence of couture. As she said during fittings, “Couture is also about relationships.”

In that spirit, there are dinners every night — Chanel on Tuesday in the courtyard of the Palais Galliera, Balenciaga on Wednesday in the Pinault family’s new art center at the old Bourse de Commerce.

The Galliera was also the setting for the Chanel show and, in the galleries, an extraordinary exhibit of the work of Gabrielle Chanel. On the way to my seat in the courtyard, I ran into Lagerfeld’s long-time muse, Amanda Harlech, whom I hadn’t seen since March 2020. The COVID restrictions and the fact that there are few journalists there — mostly American and European — has made the shows feel intimate. “I don’t necessarily want to see big shows again,” she said, “but I can’t look at a screen — I’m over it.” I handed her one of the hand sanitizers I had filched from the Vuitton party, and the air suddenly smelled of lavender.

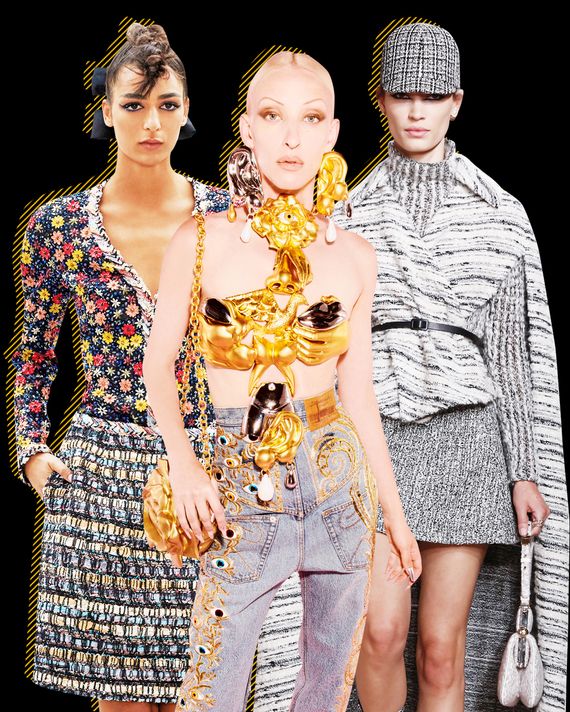

The models descended some steps from the grand colonnade of the museum, their hair plaited in faux Mohawks. Above them, the sky was gray. Though the scale of the space worked somewhat against Virginie Viard, this was her most interesting and thoughtful work since succeeding Lagerfeld. She used the colors and techniques of Impressionist painters like Manet and Morisot to create embroidered pieces, results that looked like paint strokes and daubs on classical Chanel shapes. Some of the “tweed” jackets and skirts could well have been embroidered — the house has done that before — and a red floral jacket was actually tiny feathers.

It was an astonishing display of craft, for sure, but Viard’s rendering of French painting was hardly literal, and that made the designs feel alive and modern. One of my favorite looks was a white-speckled black wool suit — lanky and relaxed, in the Chanel mode — with a plain, shimmery, water-blue sequined blouse. If some of the pinks and creams seem sprung from a garden, that was no accident. In her show notes, Viard said, “I like to mix a touch of England with a very French style.”

Flowers also exploded at Armani Privé and Schiaparelli. As lovely and ethereal as Giorgio Armani’s many tiered dresses were, his short jackets and trousers just looked unanswerably right.

Daniel Roseberry has quickly made Schiaparelli part of the conversation again in Paris, in part because he is so free at conversing with fashion’s past. “There’s a little bit of Lacroix,” he said, pausing before a nipped-waist jacket made of vintage denim with rounded, gold embroidered sleeves. There’s a little bit of Cocteau (in a jacket smothered around the shoulders with pressed, hand-painted pink roses) and shades of McQueen’s “bumster” pants (in a fanny-shaped ornament), and when I saw a glossy black cape made of “fringed” trash bags, I thought of Margiela. Roseberry has a wonderful sense of wit along with a feeling for color (think Koons), and the workmanship is impeccable.

But there’s a problem with many of the clothes; not just his, but also Viard’s and Chiuri’s. They are often visually heavy. Because they are made by hand, with minimal linings and so on, I know they feel almost weightless on the body, even Chanel’s exquisite embroidered pieces. They feel like nothing. But I’m talking about the visual effect — the too-big shoulders, the amount of trimmings and decoration (mainly at Schiaparelli). It produces a leaden effect.

I only thought of this because I saw Coco Chanel’s boucle suits in the exhibit. The three elements — jacket, top (virtually a T-shirt of its time), and A-line skirt — look blown on the body. Curious, I asked Alexandre Samson, a curator at the museum, if he knew the weight of her jackets, and of course he did. The spring jackets weigh between 13.83 ounces and 20.70 ounces, he reported, and the fall ones between 21.16 ounces and 25.78 ounces.

“A Gabrielle Chanel suit is maybe the lightest structure you could imagine in the history of fashion,” he wrote in an email.

A Chanel archivist told me it would be difficult to know if there’s been a significant change in the past 20 years without weighing a selection of jackets.

But there’s no doubt that clothes have become more complicated, more overworked — perhaps in an effort to appeal to consumers’ expectations of value. It would be an interesting exercise, though, if Viard, Chiuri, and Roseberry, to mention only three talents, were to make something that looks weightless in every sense. And couture is the place to do it. How dazzling would that be?