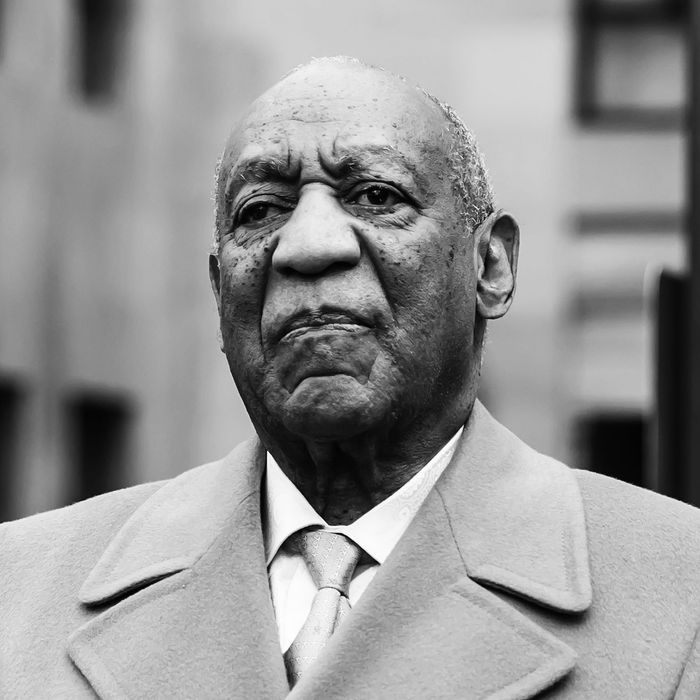

There are dozens of women, each with her own version of the same story: A world-famous comedian pressed a drink into her hands — sometimes it had a weird taste, sometimes it came with a pill on the side. A woozy feeling followed by a sudden time lapse. Confusion when she woke up with her clothes hiked up or stripped off, and Bill Cosby either on top of her or nearby. A sinking unease that solidified as fear: Who would believe an unknown teenage model, a waitress, a Playboy bunny, an aspiring actress, an assistant, over America’s dad? What would happen when one of the most prominent celebrities in the country fired back with the full force of his influence? In many cases, the women Cosby raped and assaulted stayed silent for decades, but by 2018, it appeared that the climate had shifted. After one trial ended in a hung jury, a court found the now-83-year-old guilty on three counts of felony aggravated indecent assault.

It was a watershed moment at least four years in the making: In 2014, comedian Hannibal Buress gestured to Cosby’s history of predation — 14 women openly accused him of rape a decade earlier — during a performance that went viral. For whatever reason, the accusation finally stuck: One survivor after another spoke out about Cosby’s transgressions in public, 35 of them eventually sitting down with New York to tell their stories. By the time jurors convicted Cosby, their ranks had swelled to more than 60. When she heard the news, Carla Ferrigno — who says Cosby grabbed her and kissed her in 1967, while she was on a double date with the comedian and his wife — told the Cut: “I was all worried for a long time that they were going to give him everything he needed and wanted. Consequences!”

And for a while, it felt that way. A judge declared Cosby a “sexually violent predator,” awarding him a three-to-ten-year sentence in 2018. But on Wednesday, Cosby walked out of prison with his conviction overturned on a legal technicality, without the possibility of a retrial. For those who consider the evidence against him overwhelming, the development felt blindsiding. Pennsylvania’s Supreme Court overruled the first courtroom win of the Me Too era — not because they deemed Cosby innocent, but because a past prosecutor supposedly botched his case.

In 2018, the Cosby verdict came as a shock to many of the women who helped bring him down: A year before, his first trial for the 2004 assault of Andrea Constand ended in a hung jury. But then came the raft of allegations against Harvey Weinstein, dozens of women speaking on the record about eerily similar tactics — the forced sex, the coerced massages, the threats of blacklisting and physical harm — the disgraced movie mogul deployed. Weinstein’s fall triggered an avalanche of complaints against men who’d leveraged their power to keep a lid on bad behavior. Like Cosby, Weinstein’s abuse had been an open secret for years, the influence he exerted over Hollywood running like a steamroller over anyone who threatened his reputation. But the shared experiences of so many people, across decades and countries and industries, could not be ignored. Some of the men lost their jobs, retreated from the public eye; Weinstein is now serving a 23-year prison sentence, with a second criminal case coming down the pipe.

At Cosby’s second trial, the court permitted five other women to give testimony against him, helping to prove his pattern. The jury found him guilty of penetration with lack of consent, penetration while unconscious, penetration after administering an intoxicant. “David can win and beat Goliath,” Heidi Thomas — who says that, in 1984, she awoke to Cosby forcing her to give him a blow job, after taking a sip of the drink he made her use as a prop during an impromptu reading — told the Cut after the verdict. “We hear so often, ‘our justice system is a mess,’ and this is proof that it does work.” In that moment, it felt like women might finally be believed. Now, it feels like belief may not be enough.

Wiping out Cosby’s conviction, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court’s majority opinion pointed to a “non-prosecution” agreement between Cosby and then-DA Bruce Castor Jr. You might recognize Castor as an attorney who defended another (alleged) serial predator, Donald Trump, against impeachment, but in 2005, Castor was the district attorney for Montgomery County, determining whether or not Constand’s allegations — that Cosby drugged and digitally penetrated her the year before — amounted to a criminal case. Ultimately, Castor concluded that he didn’t have the evidence to prove, beyond a reasonable doubt, that Cosby had assaulted Constand. She had been in contact with her purported attacker in the months that followed, he told Cosby’s defense in 2016, and she got in touch with a lawyer before she went to the police. In Castor’s opinion, these choices “ruined her credibility as a viable witness.” Instead, the DA assured Cosby he would not be charged if he gave testimony in Constand’s civil suit, which Cosby would settle for $3.38 million in 2006. Believing himself immune from prosecution, the comedian sat for a series of depositions in 2005 and 2006, offering a damning account of his sexual patterns.

In segments the New York Times published in 2015, Cosby recalled instructing the head of a modeling agency to send him young, “financially not doing well” women, preferably from out of town. He freely, almost boastfully, admitted to giving women quaaludes when he wanted to have sex with them. He painted this practice as regular, “the same as a person would say have a drink,” though he often gave his marks alcohol, too. Although Cosby himself did not understand them as such, his answers read as an admission. The way he described building a relationship with Constand — positioning himself as her mentor; “inviting her to my house, talking to her about personal situations dealing with her life, growth, education” — sounds like grooming; the sex he bills as consensual sounds patently coerced, the result of sedatives he expected to help facilitate intercourse.

In 2015, with allegations piling up, a new district attorney reopened Constand’s case, days before the 12-year statute of limitations expired. This time, prosecutors had Cosby on the record: His depositions played a key role in his conviction, but, ironically, they also turned out to be the thing that broke him out of prison. Per the majority opinion, to promise Cosby he would not be prosecuted for giving testimony, then use that testimony to prosecute him ten years later, constituted a “coercive bait-and-switch.” Never mind that a new district attorney had revisited the case. Never mind that the sentencing judge deemed Castor’s proposal non-binding, and that — at least according to the Times — a transcript of the deposition had been publicly available before the comedian’s arrest. Never mind the 60-plus women now standing behind Constand. Cosby’s “due-process rights” had been violated, the justices ruled. This was a question of “fundamental fairness to which all aspects of our criminal justice system must adhere.”

If Cosby had ever taken accountability, it’s possible he would have gotten out of prison after just three years anyway. In May, the Pennsylvania Parole Board denied Cosby’s request for early release, because he refused to take part in a therapy program for sexually violent offenders. He has never apologized, let alone admitted any fault: “When I come up for parole, they’re not going to hear me say that I have remorse,” he said in 2019, calling his trial “a setup.” The court seems to have agreed on that score: The justices didn’t free him because they presume him innocent — not even his lawyers said that. (“We all believed, collectively, that this is how the case would end,” is how attorney Brian W. Perry put it on Wednesday. “We did not think he was treated fairly and fortunately the Supreme Court agreed.”) In the eyes of Pennsylvania’s highest court, it is Cosby — a man who received two trials, who admitted under oath that he regularly drugged women he wanted to sleep with, and who has already settled with one accuser for millions of dollars — who was treated unfairly.

Reacting to the ruling, Constand called it “not only disappointing,” but also “concern[ing], because it may discourage those who seek justice for sexual assault in the criminal justice system from reporting or participating in the prosecution of the assailant.” And indeed, one big reason so many victims of sexual assault — 690 out of every 1,000, according to the Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network (RAINN) — never report to police is that they do not believe police will do anything about it. Of those 310 police reports filed, about 50 lead to arrests, 28 to felony convictions, and 25 to incarceration, suggesting that even if you are believed, there’s a strong likelihood it won’t translate to a court victory. When it comes to rape and sexual assault, solid evidence is usually hard to come by — prosecutors did not think Constand had enough to support her case the first time around.

Yet hers was the allegation that wound up challenging more than 40 years of alleged sex crimes, simply because the statute of limitations had run out for many of Cosby’s accusers by the time people started paying attention. At trial, the actor’s defense team tried to use survivors’ silence against them, attempting to paint their reticence to speak earlier as jumping on a bandwagon for money and clout. Meanwhile, many of Cosby’s victims have said the decision to speak publicly opened them up to harassment, threats, and trauma replaying on a loop. Those who took the stand were shamed all over again; recall the juror who, after the first trial, concluded Constand couldn’t have been assaulted, because she showed up to Cosby’s house in a crop top. The women who testified in the second trial weathered questions that blamed them for the abuse they suffered, only to have Cosby’s legal team appeal on the argument that their accounts capitalized on “#MeToo hysteria,” as Cosby’s spokesperson put it. In a case of “he said, she said,” the numbers tell us who’s usually believed. And even when the victims get the benefit of the doubt, their rapist may still walk on a technicality.

Three years in jail, international disgrace, allegations of serial rape cemented as culturally accepted fact, admitting under oath that he routinely drugged women before sex, just like his accusers said — in the end, none of this eclipsed Cosby’s wealth and “Teflon” influence. It did not wipe away his ability to keep his legal team in the game until they pulled a get-out-of-jail-free card. The same power that kept his victims silent for years kept him from serving out his sentence, just as they feared. Dozens of women. Decades of predation. Cosby’s own words. When will it ever be enough?