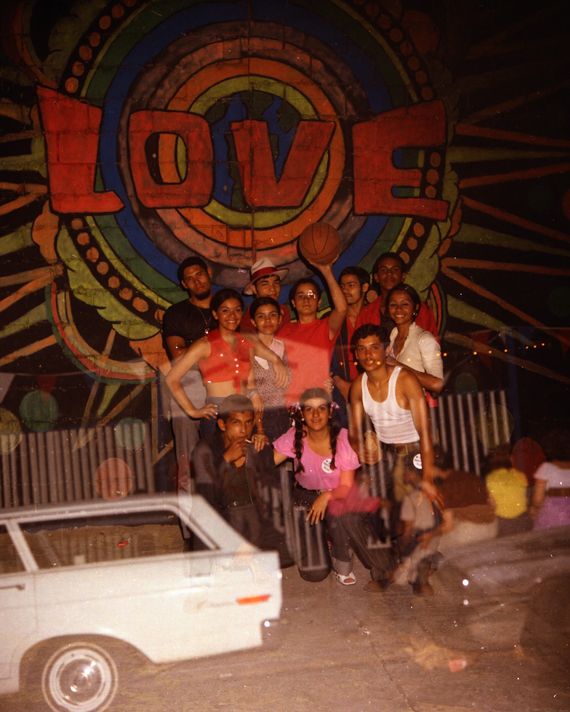

There was once a Nuyorican cultural paradise in Downtown Brooklyn. It was the summer of 1967. Two empty lots transformed into an outdoor community-led arts space, by and for the people. It was called Puerto Rican Village, and it was beautiful.

Its founder, Pablo Avilés, was a community organizer originally from Vega Baja, Puerto Rico. Avilés and his family migrated to New York City in the mid-1920s, when he was a child. Growing up in Spanish Harlem, Avilés lived in one of the most predominantly Puerto Rican neighborhoods in New York City. He put down roots in community work there, and after the birth of his daughter, he relocated with his family to Brooklyn. They settled in the area along the Columbia Street Waterfront, which was also home to a large Puerto Rican population — in part because of its proximity to the docks of the notorious New York and Porto Rico Steamship Company, which transported people to and from the archipelago and was a source of jobs for many.

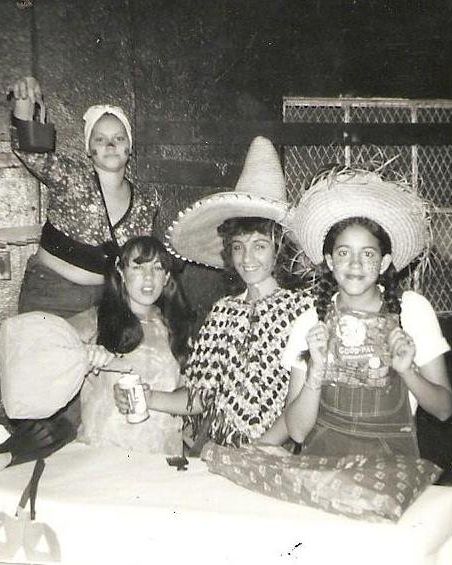

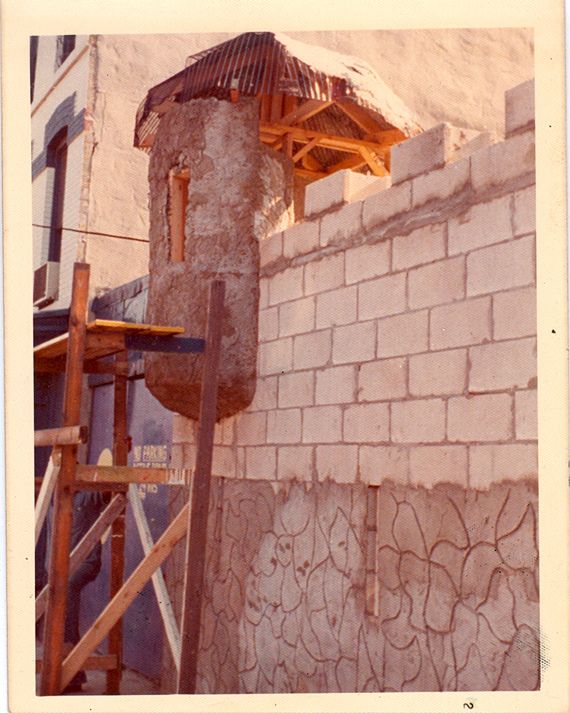

After being disillusioned by the lack of cultural programming and activities in his adopted neighborhood in Downtown Brooklyn, Avilés proposed the idea behind Puerto Rican Village to the New York City Department of Youth Services in early 1967. He often said that he felt it was his duty to advocate for his community. By the summer of that year, after a few rejections, Avilés was able to secure funding for the program, and Puerto Rican Village was quickly assembled; the financing paid people in the community, most of whom were friends of Avilés, to build the outdoor plazas alongside Columbia and Irving Streets. Many local businesses offered supplies like sand, lumber, and trees free of charge. The space was imagined as a smaller version of la isla, including a garita, a nod to El Morro, the famous castle in Old San Juan. Puerto Rican Village would offer events for the community: sponsored movie nights, concerts, block parties, parades, and skill-building classes in silk screening and photography. The performance stage was named the Antonia Denis Memorial Theater after the Afro-Boricua activist who was a trailblazer in advocating for voter rights among Puerto Ricans in Brooklyn.

Unfortunately, it was all over all too quickly. The summer of 1970 would be Puerto Rican Village’s last year after losing its funding from the city. (Avilés went on to found other community organizations, including Los Tintos Indios and the Park Row Gardens Youth Services, programs centered on enhancing the standard of living for Black and Puerto Rican people in the community.)

The history of Puerto Rican Village would’ve remained an obscure one if it hadn’t been for Nuyorican Mag, a nostalgia-oozing time capsule of all things Nuyorican. The digital photo and video archives project was founded in 2018 by Gabriella Torres, inspired by her father’s photographs of both the Lower East Side and Puerto Rico during the late ’70s. The 21-year-old — who grew up in the East Village and now studies culture and media at the New School — realized the representation in her father’s photographs was like nothing she’d ever encountered before. “I hadn’t seen an account in the digital space with a focus on celebrating and curating various mediums like photography, film, and printed materials by or of Puerto Ricans of the past,” Torres says. “So I decided to create Nuyorican Mag.” The platform exists on both an Instagram account and a website, and it focuses on amplifying social, political, and cultural contributions by sharing archival and video documentation.

The content on the archive is sourced from contact with artists who document Nuyorican history for institutional libraries; from the purchase of publications and prints on eBay; and by tapping into Nuyorican and New York City neighborhood Facebook groups, in which people often post imagery from their personal archives. Ali Rosa-Salas, the artistic director at Abrons Art Center, joined the project in 2020. Rosa-Salas is Nuyorican as well, born and raised in Carroll Gardens, Brooklyn. The two connected after Rosa-Salas came across Nuyorican Mag on Instagram and cold-emailed Torres. “I hadn’t yet encountered another account like it that focused so specifically on Nuyorican cultural production,” Rosa-Salas says. “I found myself being exposed to archival documentation and content that I had never seen before.” After a Zoom call to discuss the project, Torres invited Rosa-Salas to help curate the account, and the two have been working together since then.

For Torres and Rosa-Salas, revisiting Puerto Rican Village was essential to their chronicling of the ongoing history of Puerto Ricans in New York City. “It’s connected to my own personal heritage,” Rosa-Salas says. “And also the vision we share of the account, which is really to champion undertold stories and undertold historical narratives.” The duo discovered the history of Puerto Rican Village when Ali stumbled across a picture of it in a Facebook group called “Puerto Ricans of Columbia Street (Carroll Gardens/Red Hook).” “I was immediately captivated by the sign and needed to learn more about its origin story,” Rosa-Salas says, “because I had grown up in the neighborhood but never heard of this place!” After attempting to look up Puerto Rican Village, she found no results. So, they kept digging, and after messaging the group’s members, someone finally answered. Torres and Rosa-Salas were put in contact with Pablo’s daughter, Pauline Avilés, who is known as Nena. She shared the history of Puerto Rican Village with them, along with photographs and an insight on her father’s legacy. “With the support of Nena, we are engaged in an intergenerational historical preservation project,” Rosa-Salas says. “Having had the opportunity to write the history of Puerto Rican Village together was an important project [in] itself, as no other comprehensive narrative of the center exists.” Rosa-Salas hopes that through highlighting the history of Puerto Rican Village, they can share the lasting impact it had, since the physical space was so short-lived.

For a while, the plazas of Puerto Rican Village lived on as a repurposed space, later dubbed “Cat Village,” and became a settlement for the houseless community in the ’70s. The village was part of the casita movement, for which people repurposed empty lots into living spaces during the era’s housing crisis in New York City. Like Puerto Rican Village before it, the space came to physically resemble the countryside of Puerto Rico. With working electricity and a community garden, Cat’s Village was like an homage to Puerto Rican Village, intentional or not. Unfortunately, it too was fleeting, succumbing to fire in 1994.

Today, on what was once Puerto Rican Village lies an apartment complex, referred to as Columbia Street Waterfront. It’s impossible, especially as a native New Yorker, to miss the irony. The poor and working-class people for whom Puerto Rican Village was founded could never afford living there now. In fact, gentrification has been slowly pushing out the descendants of the mostly Black and Puerto Rican residents of the neighborhood. But the erasure of Puerto Rican Village isn’t a surprise, of course. The city, just like that Columbia Street Waterfront apartment building, is now largely inhabited by people unaware of the weight of its heritage.

In the same way that Puerto Rican Village worked to physically support the community, Nuyorican Mag works to do so digitally. Recently, Rosa-Salas and Torres created a shirt to honor the legacy of PRV, inspired by the sign that was outside the village. The proceeds of the shirt help to support Nuyorican Mag and their research, as they continue to develop an archive that’s free to the public.

Looking back on Puerto Rican Village, this is what it looks like when a community has resources, is taken care of. It’s inspiring to me, as a fellow Nuyorican, and crucial to keep these stories alive. Over the last year and a half plus, community care and outdoor cultural programming — the exact things Avilés dedicated his life’s work to — have been critical to our survival. “The fact that this outdoor art center and community space existed literally in my own backyard, and I hadn’t heard of it, said a lot to me about the importance of us preserving histories and sharing them for future generations,” Rosa-Salas says. “Puerto Rican Village emphasizes to me that nothing’s original. We’ve all been here before, and we can learn so much from our past in order to inform what we’re doing right now.”

At the opening of Puerto Rican Village, Avilés handed out free copies of a memoir he’d self-published, Pablito. He opened with a poem:

Here Lies not men but the sweat of man,

The Unknown Heroes of the war on poverty,

This battleground is lost,

But the war continues,

May god forgive us for being poor.

Puerto Rican Village was an ode to those who struggled, to a community that went unseen. Today, we celebrate it’s legacy and those who contributed to it. “I’m happy that the account can be a place where folks can learn more about their heritage,” Rosa-Salas says. “And things that are not in the history books but should be.”