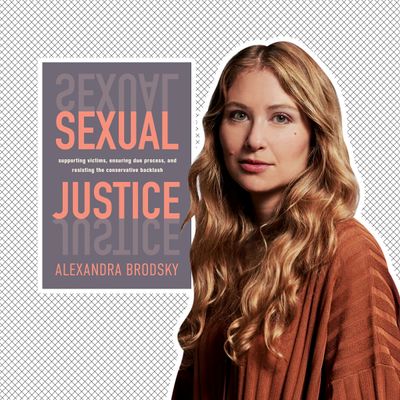

Too often, the mantra “What about due process?” is used to misdirect from a high-profile allegation of sexual harm, not express genuine concern for fairness. But attorney and anti-sexual-violence activist Alexandra Brodsky’s recent book, Sexual Justice: Supporting Victims, Ensuring Due Process, and Resisting the Conservative Backlash dares to ask the question in good faith. In influence alone, Brodsky, 31, is the gifted and thoughtful heir to Catharine MacKinnon; Know Your IX, the group Brodsky co-founded in 2013, helped transform how federal law protected students who experienced sexual assault and harassment, and a new California law making it illegal to nonconsensually remove a condom was inspired by Brodsky’s law-school paper.

That ban involves a civil penalty, not a criminal one, which is consistent with Brodsky’s argument (and the broad body of evidence) that the criminal legal system fails survivors and overwhelmingly targets people of color. Like MacKinnon before her, Brodsky argues that society must more fully grasp sexual offenses as civil-rights violations, which, she told me, “has concrete impact on people’s abilities to participate in the institution, to participate in public life more broadly, and that those individual effects accrue to promote systemic inequality.” It’s also a powerful rejoinder to claims that institutions like universities shouldn’t even be in the business of adjudicating sexual offenses. That’s not to say that those institutions always get it right — for either party. In her book, Brodsky writes that a fair process serves survivors too, but she cautions against what she calls “exceptionalism”: holding sex-related allegations to a higher level of scrutiny than others. We spoke at the book’s launch; what follows is a condensed version of our conversation.

The first question that I want to ask you is why this book, why by you, and why right now?

In some ways, the answer is these are the questions I’ve been grappling with for the last decade. I started off as a student activist working on these issues in my early 20s. From the jump, there were immediate questions about whether our efforts to ensure better support for student survivors of sexual assault were coming at the cost of rights for accused students. As is still the case today, some of those were good, important questions that needed to be solved, and some of them were just a more polite way of saying, “Aren’t you being unfair to nice boys with promising futures, whatever they did?”

In the book, you reject the binary between fairness of process and victims’ rights. I think it’s a really tough needle to thread. One of the things I was really struck by is that you say that a fair process is also an important facet of victims vindicating their rights.

I think for me it was a lot of working backwards. I had the idea for the book around the Kavanaugh hearings and thinking through what foundational beliefs, what priors, what commitments I needed to get to my understanding of what was happening in those hearings.

This sounds dismissive, but I think a lot of people don’t think of sexual assault as anything more than a crime. If sexual assault is only a crime, then it makes sense that the only fair procedure to address that allegation would be a criminal trial. Any kind of investigation that falls short of that is going to be inherently unfair. I knew I needed to start with the really basic principle that sexual harassment is a civil-rights issue, that the experience of sexual harms, particularly in the workplace or in school, have concrete impact on people’s abilities to participate in the institution, to participate in public life more broadly, and that those individual effects accrue to promote systemic inequality.

I knew that I had to start with this early history of the Supreme Court recognizing sexual harassment as a civil-rights law, then explaining the role that institutions have to play, then explaining what due process really is — not just what it is on Twitter, but what it means in the law and what ethical principles we can draw from that.

Let’s talk about a recent example of due process on Twitter. Before Andrew Cuomo resigned, you wrote in the New York Times that Attorney General James’s investigation and report was him getting his due process. Obviously, not everyone agreed — Kenneth Cole, the then-governor’s brother-in-law, tweeted that there hadn’t, in fact, been due process.

I think that this is really tricky, and part of it is that the term “due process” is so indeterminate. I have to turn off my lawyer brain a little bit because, as a strictly legal matter, due process only applies to circumstances where the government is trying to take something away from someone. I would say 80 percent of the time when we’re talking about due process and allegations against people accused of sexual harassment, it doesn’t apply at all.

What I have to remember, turning on my human brain, is that when we refer to due process, we’re generally not thinking about the specific legal rules but the ethical principles that underlie those, because those ethical principles have shaped the law and are shaped by the law. Whatever is required by law, as a matter of fairness, as a matter of ethics, we want people who’ve been accused of any kind of misconduct to have the chance to tell their side of the story, the chance to present their evidence. What both the law and common sense tell us is that it’s going to look different in different contexts. No longer being governor just isn’t the same as going to prison. If Cuomo is ever criminally tried, he will absolutely have the right to a full trial with a jury with a cross-examination, but that’s not what’s at stake in an impeachment hearing.

And I think people know that. We make decisions in our own lives about the people around us and who we’re going to spend time with, where we’re able to come to judgments without going through a whole hearing every time there’s a conflict between two friends. We can draw from that basic principle to think about what the correct process looks like in different contexts with different stakes.

In your book, you introduce this concept that I think is really helpful: exceptionalism, which is that we treat sexual offenses in a different way than we do nonsexual ones.

So many people just assume that an allegation of a sexual nature requires uniquely onerous investigatory procedures. They’ll be totally cool with a workplace terminating someone based on an informal conversation in an office, but once we’re talking about sexual harassment, everyone assumes we need a federal judge in robes. At the heart of that is misogyny, and there’s been really wonderful feminist historical and theoretical work, including by Michelle Anderson, laying out how this is nothing new. This kind of exceptionalism was really baked into American criminal law until quite recently.

I worry what a freshman learns when they see that their friend accused of punching someone in the face or using slurs of a nonsexual nature is subject to one process, then that their classmate accused of sexual assault is subject to another process that requires significantly more vetting, a higher standard of evidence, a different, more adversarial kind of questioning, and that what they’ll take away from that is allegations of sexual harm are uniquely suspect and the people who make those allegations, who are overwhelmingly women, girls, and nonbinary people, are uniquely deserving of incredulity.

You’re critical of exceptionalism, but in the book you’re also critical of when feminists say of someone who loses their job, “Well, no one is entitled to that big job.” I was surprised to read you expressing some concern with how the Al Franken case went down. Specifically, you say that, if you were a senator, you’re not sure you would’ve called for his resignation based on what facts were out there.

It has to, of course, be true that losing your job is tough and also that it is different than going to prison, and that we, as advocates, have to be able to hold both those truths at the same time. It is a huge bummer for Al Franken personally that he is not a senator anymore, and also, he didn’t have a legal right to that. He didn’t need a criminal trial to be removed from that office. The question is just, what was appropriate there?

My take on Franken in the book is that I think really so much of the debate is actually confusing substance and process. If I remember the Jane Mayer article defending Franken, which was basically just a lot of people saying that what Franken had done was not as bad as what Weinstein had done or what Roy Moore had done — based on what we know, that appears to probably have been true. That’s not really a question of due process. That’s a question of, how bad is bad enough to be removed from public office? And we should have that conversation; we should just not pretend it’s about process because procedural fixes aren’t going to solve definitional questions. Having a more elaborate hearing isn’t going to help us to figure out as a society what is conduct that we think is okay and what is conduct that we don’t think is okay.

For the book, you also talked to people who were accused of sexual harassment at school and at work. Tell me about how those conversations went — you mention in an aside that some of those people lied to you or weren’t fully forthcoming with the facts.

It’s very hard, when you’re sitting with someone and listening to a really difficult time in their life, to not feel connected to them. I was genuinely touched that people were willing to trust me, even though I think they saw me, not unreasonably, as from “the other side.” I think that some of them genuinely were wronged. For me, the most disturbing stories were from victims of sexual abuse who had been accused of the same by their abuser as sort of part of their abuse. I was very sympathetic to those.

I was really wary of falling into what Kate Manne calls himpathy, which is this knee-jerk reaction for men accused of hurting women that excludes any concern for the woman … I have thought I was in a conversation with someone grappling with these questions in good faith; then, 20 minutes in, I’m like, “Oh, you just think that no one gets raped. Huh. That strikes me as coming from a different perspective here, that we’re probably not going to have a fruitful discussion.”

I was really worried about being manipulated by someone who had been accused of a sexual harm, because of their tendency to manipulate. I was really concerned about writing a book that was going to end up being propaganda for people doing exactly what I fear, which is using concerns about due process as sort of a fig leaf for their true ends of impunity. I constantly felt like I was walking this really narrow line. I hope I succeeded, but it was tough and I can see how someone could’ve been drawn in to thinking that they were just helping a system function well when they really were choosing a side.

How did you find the accused men you interviewed?

I found them online; I found them through attorneys. One thing that one guy said really stuck with me. He said that the only people who had ever wanted to hear about his experience before were men’s rights activists, and he wants nothing to do with men’s rights activists. He’s sympathetic to Me Too. He’s telling me he thinks that allegations are usually true, they just happened not to be in his case, and he wanted to tell someone about this experience. He wanted to see procedures at schools like his improved, and there just hadn’t been an opportunity for him to do so.

I was impressed by your optimism — specifically your belief that there can be a better process. Given how much time you spend with systems that failed, how do you still come away having done this work and written this book thinking that there is a better way for process and for systems to function?

I think there are two sources of my optimism. One is remembering how new this project is. I started college in 2008, and that was genuinely a different universe when it comes to Title IX and sexual-harassment procedures that students are in now. I don’t want to sugarcoat it. Things are tough right now, especially because of some Trump-era regulations that are still in place, but half the schools had no idea that Title IX had anything to do with sexual harassment. They hadn’t even tried to put together a good process yet. I feel like we are really just at the start of figuring out these hard questions.

I don’t want to understate the complexity, but when you really sit down with people, even people from the “other side,” and you say, “What do we actually disagree with? Where’s the source of our actual tension?” when it comes to process, it’s what kind of subtle differences in questioning models, it’s slight tweaks here and there to procedures. Again, excluding people who are actually just trying to make sure that survivors can never come forward and just trying to create the most onerous procedure possible. There’s just so much room for agreement when we can actually sit down together in the room and figure it out. I’m not Pollyanna-ish; I know that there’s trouble ahead. But I think we can get there.