Dream Date: Brushes with our celebrity crushes

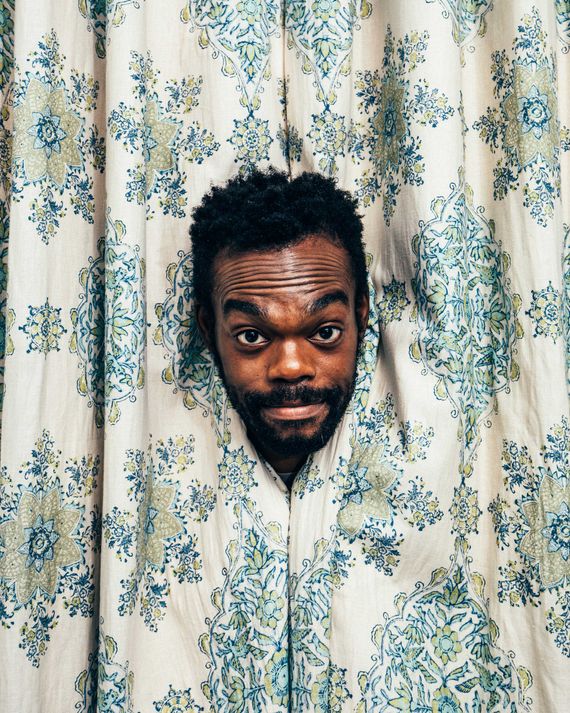

William Jackson Harper has the ineffable quality that comprises a male romantic lead. The role is a thing of gravitas that cannot be learned or taught, but rather is comprised of an innate, mystical quality that one just has. If it’s contrived, it will buckle under the judicious scrutiny of femme cultural desire. Good looks or, in academic terms, the quality of looking like a “snack,” is but a fraction of what it takes. Although I speak to Harper on Zoom while he holds his cell up in the back of a taxi on the way to a shoot — mask on, glasses on — this particular charisma permeates through screen and spectacles and patchy technology. Even with a slither of face exposed, his eyes do the work of conveying an endearing earnestness, a twinkling self-deprecation. There is a sincerity that all successful romantic leads possess that conjures the notion that you could feasibly meet this man in real life and have the urge to immediately text your group chat to inform them you have possibly met your future husband. Sweet, then, that when this is touched on, Harper becomes almost bashful: “I never saw myself in that light.” And yet, he glows within it. When I speak to Harper, star of comedy The Good Place and liberation drama The Underground Railroad, it’s the morning after the second-season premiere of HBO’s romantic anthology Love Life. He helms the funny, tender, and devastating season, which explores the notion of love being a journey rather than a destination, as messy but sweet book editor Marcus Watkins. Harper had two drinks the night before at the celebration; he claims wryly, voice dry, that at 41 years old, it means he is in for a “long, long day.” Despite the presumed hangover, Harper is thoughtful, engaging with real consideration and intent. It’s easy to sense that his sincerity is how he brought a grounded humanity to Marcus, a character who — though often chaotic — is ultimately good, in the true sense, in the human sense, in the everybody-is-an-asshole-sometimes sense. When challenged to look inward with brutal frankness, in episode ten, Marcus sums himself as “a complicated softie prone to juvenile fuckups.”

It is refreshing to see a man openly and baldly calling himself a “softie” without it being posited as a deficiency. I ask Harper how he identifies with softness himself. I hear his smile when he says, “I’m definitely soft, in every sense of the word. I’m very stereotypical in the way I manifest my emotions … which is almost not at all. That doesn’t mean that I’m not incredibly sensitive. And I think it would be really beneficial for men to be able to express that without society pointing and prodding. I think a lot of men are more sensitive than they let on.” Ironically, the fact that Harper is able to identify this implies he is probably more open with his emotions than he thinks.

It is also notable that this confession of vulnerability happens to be coming from a Black man playing a romantic lead on a major network. When asked what drew him to the role of Marcus, Harper says he was intrigued by “the fact that he’s just a mess. He’s a guy that feels his life should look a certain way. He judges himself for being this age and making these messes, because that’s not the dude that he is, as far as he knows.” Though he acknowledges that we don’t often get to see the romantic comedy through the lens of a Black man, especially one so emotionally complex, he is quick to assert that they exist — it’s just that they aren’t paid attention to. The normalcy is what spoke to him, the fact that the shift from a white woman to a Black man as the romantic lead of the series wasn’t “concerted” but rather the “next logical story to tell. And the fact that I’m getting to tell it is really special.” And what makes it special? “Marcus is just a guy, living his life and going through the world.”

Perhaps, then, it isn’t a coincidence that the men Harper plays have a tenderness to them. In The Good Place, he played gentle neurotic nerd Chidi Anagonye, a role he mercifully landed in his 30s, when he reckoned that “maybe this whole acting thing isn’t the thing I was supposed to be doing.” Like Marcus, who is frustrated by an unfulfilling career, Harper was trying to reconfigure who he was in the midst of looking for a break, frustrated by “not being able to be the friend that I wanted to be, because I was always chasing the next thing. I wasn’t able to be the son I wanted to be, the partner that I wanted to be, because I was just nervous and scared and I really didn’t want to feel like I was just missing out on life.” Landing a role on The Good Place, he says, “saved” him. He made a resolution to himself: “I’m gonna give it one more shot. I’m gonna not say yes to everything just to keep acting, but be more judicious about it.” He realized that “maybe it’s okay for the pursuit of this particular field to not be the center of my life. It gave me a little more faith, gave me a little more room to breathe”; it also validated him, letting him know he was on the right path.

There is a candor to Harper. He often stills to consider a question and gather his thoughts, and when he shares them, the answer is thorough, with an acknowledgement of his perceived pitfalls. He isn’t afraid to offer up his interiority. The allure of the rom-com boyfriend isn’t that he is perfect, but rather, that he is open to growth with the knowledge that he isn’t. Harper is refreshing in his unaffectedness — when I mention that I just began my 30s, his eyes light up playfully behind his glasses, and he says, in a tone that is impossible to bristle at: “Man, you’re gonna go through shit.”

The fact that William Jackson Harper never saw himself as a romantic lead is perhaps what makes him a compelling one. It’s major in that it shouldn’t be, shattering the rigidity of the mainstream archetypical rom-com crush. “I just never felt like I was the guy that people would want to see in that role. I’ve always been such a nerd, so I never thought that that was where I was headed. That’s the thing that’s fun about playing Marcus. I get to come at it from my point of view. My point of view is less sentimental, and in a lot of ways my outlook is less romantic, but the romance is coming from the situation and the honesty that the characters are having with each other rather than leaning into the idea of what romance is supposed to be.”

Playing a romantic lead — someone so unlike how he saw himself — was revelatory for Harper. “I learned how vulnerable I feel when it comes to expressing that kind of emotion. I feel like a little kid, you know? Like it’s mushy, and I have to push past that. I’m a 41-year-old man! This shouldn’t be such a frightening thing.” Casually, he adds, “I should probably talk with a therapist.” I’m sure playing Marcus Watkins, a man so fraught with feeling, was a form of therapy too.

It definitely brought Harper some emotional clarity. “Marcus was always hiding, and more than anything, he just needed to be able to say, ‘I don’t care how this goes. I just need you to know that I love you. And that’s just what it is.’ There’s a real value to just saying you don’t have to say anything back to me. There’s something in just saying it and having it be in the air that’s really purifying.”

Like some sort of thirst messenger, I inform Harper that his role of Marcus may see him become an Internet Boyfriend, and I ask him how he’s preparing for the attention that the hallowed role will bestow upon him. He chuckles warmly in a way that breezily balances confidence, humility, and appreciation and says he doesn’t want to get a big head: “I’m too old for that.”

Rather than disrupt the archetype of the romantic lead, Harper highlights the power in its breadth. As Marcus, and hopefully in many other future romantic roles, Harper triumphs, and it is clear it is because he shares himself with his characters. The Internet Boyfriend crown rests easy on William Jackson Harper’s head, although he isn’t sure if it fits. He still sees himself as a “left-to-center weirdo.” Perhaps that’s why it works. Like Excalibur or Mjölnir, the role of the romantic lead only works when one is worthy. It’s not about one fitting into it; it’s about it fitting onto the deserving.