The only moment that felt real in today’s Supreme Court session on whether or not Americans will lose our fundamental right to access abortion occurred about 20 minutes in. Justice Sonia Sotomayor, speaking slowly and gravely, was asking Mississippi’s solicitor general about a more recent abortion ban enacted by the state legislature, one that is even harsher than the 15-week ban before the Court. The lawmakers had been straightforward in saying that they were introducing the more draconian law, which bans abortion at a staggering six weeks, because there are now more conservative justices on the court and they could more likely get away with it. They had made their agenda plain — not just to ban abortion at 15 weeks, but to overturn the right enshrined in Roe v. Wade altogether — and those new justices had taken up the cause without missing a beat. Yet the Court was carrying on with oral arguments as if this collusion was not directly opposed to its mandate of impartiality.

“Will this institution survive the stench that this creates in the public perception,” Sotomayor asked, “that the Constitution and its reading are just political acts? I don’t see how it is possible.” Her words were a brief moment of catharsis, even as the arguments went on and it became ever more clear that enough justices are willing to rule to overturn Roe. It was a bizarre relief that the terms of her question were so stark, that they actually acknowledged the precipice we are standing on. Will the court survive this? Will our democracy survive this? That’s how big, how terrifying the implications of this decision are.

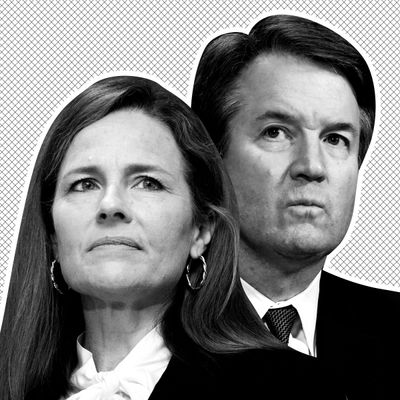

Everything else was legislative theater — a sickening act of propriety, legal argument, and supposed objectivity cloaking the source of that rotting stench Sotomayor had detected: a fanatical right-wing political movement hell-bent on controlling and marginalizing certain groups in our society. The Mississippi solicitor general and sympathetic judges rattled off the justifications for overturning Roe that they have been honing for decades in Federalist Society–funded law journals and briefs, ranging from the misleading and nonsensical to the offensive and disturbing. Brett Kavanaugh called the right to choose “divisive” despite most Americans supporting Roe; Scott Stewart, the Mississippi solicitor general, claimed laws surrounding women’s work and health care now made the right to abortion unneccessary, because parenting is no longer the undue burden it once was, despite the United States having some of the least effective parental support on the books. He claimed that “science” has changed the terms of viability — which previously protected the right to access abortion under Roe — but could not say exactly how. Amy Coney Barrett suggested that women could simply carry on with their unwanted pregnancies and give birth to children before giving them up for adoption, and that this would “take care of the problem” of unwanted parenting. She was including, it should be noted, victims of rape and incest in this senario, proposing that they should carry fetuses created by abuse and violence in their bodies to full term.

But the most sinister argument is the slickest one, the one that the justices, should they uphold the Mississippi ban as they seem poised to do, will emphasize: that overturning Roe is somehow a middle ground that merely returns the right to choose back to the states for consideration, and that this is somehow a moderate viewpoint that should be upheld by the court. “The Constitution is neither pro-life nor pro-choice on the question of abortion,” Kavanaugh reasoned, “but leaves the issue to the people of the states or perhaps Congress to resolve in the democratic process.” As if overturning half a century of law is not a radical ideological shift but a pure, unadulterated rereading of that law grounded in reason. The narrative that took shape was beyond galling — it was maddening.

Because nothing about the far right’s ideological project pushing for forced birth is even about the ethical, scientific, or legal considerations around abortion itself. It’s about control. Powerful people, like those on the court and their families, friends, and peers, will continue to get abortions. The justices know this. People who can afford it will travel to get them where they can. They will have access to materials that tell them where to go and what to do, the funds to get them there, the means to hop through whatever hoops to get one; they will not be stopped by losing a ride or by not being able to swing a hotel room or by the people who try to convince them they will be shunned, arrested, or harmed for their decision. What’s at stake are the futures of millions more people who cannot overcome these hurdles — poor women, poor people, people of color, the undocumented — many of whom already live in places where these barriers effectively keep them from terminating pregnancies. The forces behind the anti-choice movement want these groups to remain marginalized under the law, full stop. And yet we were just submitted to two hours of Latin-inflected intellectual debate pretending that isn’t what’s happening.

When I think about how ultimately unencumbered I have felt in moments of real crisis because I knew I could get an abortion if I needed to, my heart breaks for those whose worse-case scenario will not end with that saving grace. What helps is to think about the people and organizations on the ground who have been battling for justice and bodily freedom in the vast landscapes across the United States that are already effectively post-Roe: abortion funds, abortion doulas, clinic defenders, mutual-aid networks. Their efforts deserve the fuel of our anger.