About a year ago, my 8-year-old niece was giving me a tour of her at-home desk setup, where, among glitter pens and cookie-shaped erasers, I spotted a big red stress ball. “Is that mom’s?” I asked, recognizing it as the kind of thing usually found in adults’ offices. It turned out it belonged to her, and when I wondered what she needed it for, she explained, “I’m so stressed out right now.”

I don’t have kids, but it wasn’t long before I noticed that the homes of people who did were full of things their children could squeeze, pull, punch, and poke, ostensibly to help them relieve stress. At a toddler’s house, I came across a ten-pack of Squishmallows, squeezable stress balls disguised as animals. Back at my aunt’s, a look inside her 6-year-old son’s toy box revealed a menagerie of thick, floppy noodles that could withstand aggressive stretching and twisting and plastic tubes designed to expand and collapse like giant bendy straws. One friend’s 7-year-old seemed to have a normal stuffed-animal collection, until it was revealed that some were weighted to help relieve anxiety.

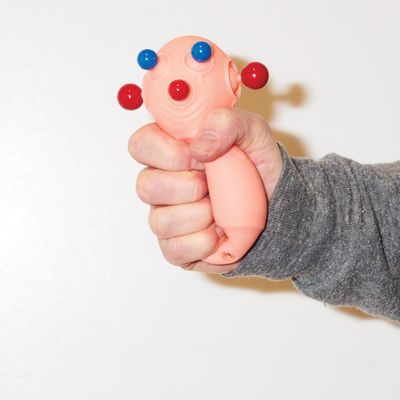

These trinkets are part of a new category of toys known as “fidget therapy” or “sensory stress relief” toys, or simply fidgets. Ritzy kids’ boutiques stock them in sections labeled with wellness-y phrases (“Foster your child’s mental health,” help them “achieve true tranquillity”), while bodegas and CVS’s throw them in the tubs next to hand sanitizers. For the past few months, a handful of fidgets have rotated to the top of Amazon’s best-selling-toys list; last I checked, a “fidget cube” that purports to “soothe nerves” was at the top of that list, and in second place was a stuffed octopus “for stress relief.” The hottest fidget on the market is the Pop It! Made of multicolored silicone, the Pop It! and its pop-toy competitors (OMG! Pop Fidgety!, Dimpl Pops) are basically reusable Bubble Wrap — you press a penny-size button down on one side, and it pops up the other; flip it over, repeat. A representative from FoxMind, the company that manufactures the Pop It!, said it saw sales increase tenfold in 2021.

“The kids are obsessed with them,” says Kayla Prewitt, a Washington State–based elementary-school counselor. “I literally see 200 a day, and they’ll choose my fidgets over Play-Doh, watercolors, whatever.” Her students are usually covert about the toys, keeping them on a keychain or in a pencil case, but she’ll sometimes catch a kid trying to lug a jumbo-size pop toy into the classroom. “I guarantee every elementary-school educator has had to confiscate at least one fidget in the last year.” One Manhattan mom told me that her kids started begging for fidgets after being spammed with “unboxing videos” on YouTube, where child influencers squeeze, knead, and mash their way through boxes of fidget toys, chattering about their size and color and comparing them to their existing hoards.

At first glance, the toys appear to be the physical manifestations of two years of pandemic life. The stress of adults and caregivers surged, and that cascaded down to their children. But according to Dave Anderson, a clinical psychologist with the Child Mind Institute, fidget toys predate the pandemic by years. The craze probably began with the fidget-spinner mania of 2017, which got so out of hand that some school districts banned them outright. Those were soon replaced by sensory toys that went viral online: Kids and teens could be seen dribbling fluorescent slime into their drinks and slicing up Kinetic Sand (silicone-coated, squeezable sand) on social media.

What has changed in recent years, says Anderson, is the way we as a society are thinking about and diagnosing stress and anxiety. “Today, parents are hearing more than ever about how important it is to give their kids mental-health-and-wellness skills,” he says. That concern is being echoed in schools. Around the country, district spending on SEL (“social-emotional learning”) programs — curricula to help kids comprehend and handle emotions — grew nearly 45 percent between November 2019 and April 2021. (My niece, as it turns out, got her stress ball from one of these classes.)

According to Anderson, a pop toy or a child stress ball is, on its own, no different from a blanket or stuffed animal or any object a child might hold for comfort. The fidget-toy craze, he believes, is “an old strategy meeting with a marketing machine”: “If you’re being told that your role as a parent is to provide mental-health skills to your kids, and you see something you could buy that purports to have a stress-relieving effect, you’re hitting the sweet spot for parents.”

After noticing fidget toys taking off during the pandemic, the Toy Association, a trade group that represents the U.S. toy industry, officially named the trend. “Zen-sationals,” says representative Jennifer Lynch, are toys that “promote mindfulness, self-care, and encourage kids to process their emotions in a healthy way” and include pop toys and fidget spinners as well as things like essential-oil-infused “therapy dough,” emotional-support activity sets, and puzzles that teach empathy. And many toy companies with existing lines of products have, in recent years, simply rebranded: A few years ago, Kinetic Sand started selling “Zen gardens” with a mini-rake and shovel, and Squishmallows began tweeting about the stress-relieving effects of its stuffed animals. The Pop It! is also the product of a makeover. It hit toy fairs as a logic game in 2013 but really took off when Buffalo Games, one of its distributors, started selling it at Target as a fidget toy in 2019.

Naturally, “Zen-sational” branding speaks directly to worried parents. “I don’t normally hear a 7-year-old say, ‘Oh my gosh, I have to get this because it’s so stress-relieving,’ ” Anderson says. Instead, what seems to be drawing kids to fidgets is their collectibility; they have become, as one parent told me, “the most popular trading toys on the playground. One girl trades another for a fidget they don’t have, like what I used to do with stickers.” My 6-year-old nephew told me that he never plays with his Squishmallows and only brings them to school to trade: “Like Pokémon cards, but more of my friends want these right now.”

“At school, they’ll tally up how many fidgets they have, how many they can trade, who’s getting more for the holidays,” says Lyss Stern, an Upper East Side mom whose teen boy and 7-year-old daughter use fidgets. “The toys can wind up creating even more pressure for kids than they reduce.” Stern’s 7-year-old found out about fidgets at camp but was dismayed when the other kids would only trade pop toys for other pop toys. “I begged my parents, ‘Please, get it,” she told me. “It only cost $8, and they finally got it from Amazon.”

While their Beanie Babies or action figures may risk getting confiscated, kids seem to have figured out how to talk about fidgets using the language of stress-relief in a way that placates adults. “Honestly, I never see them playing with them,” mused another Manhattan mom. When she asked her 8-year-old why she was bringing a fidget to school, the child claimed that it “relaxes” her. “She was fed the language, I think, by the marketing geniuses at YouTube,” the mom said.

Perhaps this latest toy era is priming kids for a stress-infected adult world; maybe grown-ups invented these things to give kids a glimpse of what is to come, all while deluding themselves into thinking it might better prepare them for it. But Anderson, whose kids have some fidget toys, is more sanguine. Both he and his wife are psychologists, and they purchased pop toys for their kids — “Not because we believe they possessed great stress-relieving properties,” he says — but because they’re basically harmless and might help his kids deal with “big feelings’’ when they’re bored or upset. He has observed his 5-year-old stare at his dinosaur-shaped pop toy in a quiet moment and his 2-year-old play with hers when she wants to relax, probably because it’s her favorite color, purple. But then again, when his kids are mad, the toys simply become projectiles to throw at each other’s heads. “At that moment, they don’t seem to be serving a stress-relieving purpose.”