March 16 marks the one-year anniversary of the Atlanta-spa shootings, in which a lone gunman targeted and murdered six Asian women — Daoyou Feng, Hyun Jung Grant, Suncha Kim, Soon Chung Park, Xiaojie Tan, and Yong Ae Yue — working in massage parlors across the city. The women were beloved business owners, mothers to 20-something boys, grandmothers who loved to line-dance.

The murders, which took place during a rising tide of anti-Asian violence in the U.S., were hate crimes, even if law enforcement refused to call them such. They stoked fear, grief, and outrage throughout AAPI communities. One year later, there has been no recovery from that grief, only more wounds. Anti-Asian crime continues to rise; it increased by 339 percent nationwide in 2021 alone. This year, we have already witnessed brutal and unprovoked hate crimes, frequently against women and seniors, who tend to underreport crimes because of language barriers and uncertain immigration status.

“With all that’s happening, I see how much more valuable this type of work can be to a lot of families and Asian American people,” says Queens-based photographer Janice Chung, 29, of her photo series “Who Are You?,” an intimate study of her Korean American identity. The images were captured in Flushing, Bayside, and Fresh Meadows, in the places where Chung grew up: her grandmother’s “big house,” or keun-jip; her great-aunt’s apartment; her parents’ home. Populated by family members both living and dead, as well as by candids of domestic life in an intergenerational family, the series is a nostalgic window into childhood, a time before everyone grows up and scatters. “I think we just need an opportunity to get to know one another, to be seen, to be validated,” Chung says. “If I could present this narrative about family and nostalgia, maybe people can see themselves in this work, whether they’re Asian American or not.”

When Chung first started taking these photographs in 2013, she didn’t intend for anyone to see them. They were a personal exploration of her identity and place within her family. “I was just looking for connections and opportunities to refamiliarize myself with people and places that maybe I’ve taken for granted,” Chung says.

She took the images one by one over the course of four years, not knowing that she would later assemble them as a single body of work. And yet they coalesce into a cohesive photo-memoir; looking at the images feels like turning the pages of someone’s well-worn family album. There are 101st birthday parties, funerals, rooms where sleepovers once happened, and trappings of everyday life — memorabilia that may not have much monetary value but is precious all the same.

Chung has included portraits of family members: her baby cousins and her cousins having babies, her father watching television. In her favorite image, she is eating cherries at her elderly aunt’s apartment. For her, that shot captures jeong, a Korean term for your connection to people and places you spend time with. “It doesn’t necessarily mean positive feelings,” Chung explains.

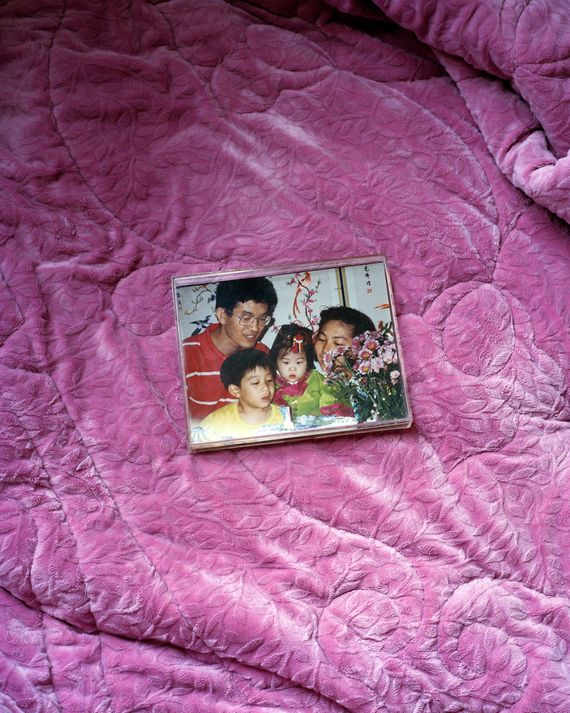

Through photography, Chung has discovered a way soften the language barriers that distanced her from her elders — it’s not a bridge, per se, and perhaps nothing can be, but at least it fills the silence. Still, voids are inevitable in any project of childhood memory. At several points in the series, Chung takes photos of childhood photos. Some memories can’t be faithfully evoked through re-creation; only the real thing will do. That said, “things are not always picturesque” in reality. For Chung, photos inside photos are romantic narratives of family life. They preserve a sense of idealism that doesn’t exist anymore. Maybe it never did. “I’m really trying to hold this faultless idea of what family is or should be. Or could be.”

While Who Are You? focuses on Chung’s father’s side of the family, she tells me it’s her mother who most helped her understand her place in the family, as well as understand herself. Perhaps that’s why the series offers up such astute observations of Chung’s mother, whether through portraits or photos of her daily rituals. In A Bath for the Plants, Chung captures her mother’s ritual cleaning of houseplants in the bathtub, though her mother is not in the frame. This is the most frightening aspect of family love, an awareness that permeates the whole series: Those who anchor you, who show you who you are, won’t always be with you.

This is my grandma’s house in Flushing. We call it Keun-jip in Korean which translates to “big house.” The big house is usually where the oldest son lives and where the mother resides — the mother being my grandmother. This is where I spent many years running around as a child, from sleepovers to large holiday gatherings with extended family. It was always literally and figuratively the Keun-jip.

Being married to the youngest son in the family meant that my Umma (mom) had to do a lot of the work in the family. At least that’s what she told me. It’s hard to describe what her relationship with the family is.

Umma gives her plants a bath every spring to cleanse them of the dirt and dust piled atop their leaves. It’s a yearly routine for my mom, but with her aging, I’m not sure who will take care of them in years to come. Maybe me?

My Appa (dad) is pictured watching TV in our apartment. While we aren’t super-close, if there’s one thing we had in common, it was our mutual love for watching a ton of TV, especially music-related programs — his in Korean and mine a trashy American reality-based version.

My Halmuni (grandma) shared love in the form of hand-holding or hugs, even if she could not walk or speak as lucidly as she used to. This photo was taken on her 101st birthday with many of her great-grandkids and grandkids in her home, the Keun-jip.

Halmuni was a religious woman. She always had the Bible by her bedside, and whenever she could, she prayed before her meals. Besides her Bible, she always had photos of her grandkids and her medicine close by.

My mom and I visited my Keun-gomo, which translates to “big aunt.” She is my oldest aunt, old enough to be my grandmother. My Keun-gomo and Keun-gomobo (big uncle) helped raise me. They lived next door, and I remember the way their home smelled of ancient Korean herbs. In the photo, my Keun-gomo resides in her senior apartment but is mostly bedridden. I had not seen her for a while, so I remember feeling surprised at how much she had changed. I always remembered my Keun-gomo as tall and intimidating. For the first time, I was seeing her as the opposite.

This is my Keun-gomobo’s room.

Because I was the youngest granddaughter of the youngest son, my grandmother was always a lot older than most people’s grandmothers. As an adult, I began to spend more time with her, but with my limited Korean and her advanced age, there was little we could communicate. If I were maybe ten years older, would that have changed anything?

When he was born, Michael became the first third-generation Korean American in our family in Queens.

Leah and Chloe are sisters — children of my oldest female cousin in New York, Lisa.

In the final years of her life, I remember my Halmuni sleeping a lot. She passed away maybe a year or less after I took this photo. If there’s one thing I’m grateful for, it’s that photography allowed me to spend more time with her, even if we passed the time in silence because of the language barrier.

My Halmuni lived to 102 — she died just two weeks shy of her 103rd birthday. As her youngest granddaughter, there are so many things I wish I had asked; there were so many words left unsaid. Despite this, I have gratitude for having been in her presence throughout my childhood and into my early adult years.

Halmuni’s burial took place in 2017. Three generations of family members were present: my Halmuni’s kids, her grandkids, and her great-grandkids.

This is a photo of my Halmuni and all of her eight kids.

This is my grandma’s house in Flushing. We call it Keun-jip in Korean which translates to “big house.” The big house is usually where the oldest son lives and where the mother resides — the mother being my grandmother. This is where I spent many years running around as a child, from sleepovers to large holiday gatherings with extended family. It was always literally and figuratively the Keun-jip.

Being married to the youngest son in the family meant that my Umma (mom) had to do a lot of the work in the family. At least that’s what she told me. It’s hard to describe what her relationship with the family is.

Umma gives her plants a bath every spring to cleanse them of the dirt and dust piled atop their leaves. It’s a yearly routine for my mom, but with her aging, I’m not sure who will take care of them in years to come. Maybe me?

My Appa (dad) is pictured watching TV in our apartment. While we aren’t super-close, if there’s one thing we had in common, it was our mutual love for watching a ton of TV, especially music-related programs — his in Korean and mine a trashy American reality-based version.

My Halmuni (grandma) shared love in the form of hand-holding or hugs, even if she could not walk or speak as lucidly as she used to. This photo was taken on her 101st birthday with many of her great-grandkids and grandkids in her home, the Keun-jip.

Halmuni was a religious woman. She always had the Bible by her bedside, and whenever she could, she prayed before her meals. Besides her Bible, she always had photos of her grandkids and her medicine close by.

My mom and I visited my Keun-gomo, which translates to “big aunt.” She is my oldest aunt, old enough to be my grandmother. My Keun-gomo and Keun-gomobo (big uncle) helped raise me. They lived next door, and I remember the way their home smelled of ancient Korean herbs. In the photo, my Keun-gomo resides in her senior apartment but is mostly bedridden. I had not seen her for a while, so I remember feeling surprised at how much she had changed. I always remembered my Keun-gomo as tall and intimidating. For the first time, I was seeing her as the opposite.

This is my Keun-gomobo’s room.

Because I was the youngest granddaughter of the youngest son, my grandmother was always a lot older than most people’s grandmothers. As an adult, I began to spend more time with her, but with my limited Korean and her advanced age, there was little we could communicate. If I were maybe ten years older, would that have changed anything?

When he was born, Michael became the first third-generation Korean American in our family in Queens.

Leah and Chloe are sisters — children of my oldest female cousin in New York, Lisa.

In the final years of her life, I remember my Halmuni sleeping a lot. She passed away maybe a year or less after I took this photo. If there’s one thing I’m grateful for, it’s that photography allowed me to spend more time with her, even if we passed the time in silence because of the language barrier.

My Halmuni lived to 102 — she died just two weeks shy of her 103rd birthday. As her youngest granddaughter, there are so many things I wish I had asked; there were so many words left unsaid. Despite this, I have gratitude for having been in her presence throughout my childhood and into my early adult years.

Halmuni’s burial took place in 2017. Three generations of family members were present: my Halmuni’s kids, her grandkids, and her great-grandkids.

This is a photo of my Halmuni and all of her eight kids.