At the beginning of the pandemic, Anna, a Polish woman, was almost 12 weeks pregnant and the abortion pills she had ordered from overseas were late in arriving. Since Poland enforces a near-total abortion ban, she had hoped to go to Germany for the procedure, but her husband told her if she traveled with their young child, he would have her arrested for kidnapping. So Anna called the hotline for Abortion Without Borders, a network of groups in Poland and across Europe that arranges abortions for people by helping order abortion pills to their homes or by helping them with the cost and logistics of traveling abroad.

Justyna Wydrzyńska answered Anna’s call. Now 47, Wydrzyńska had been in a similar situation at 33 with her own controlling husband, whom she has since divorced. Wydrzyńska sent Anna, who said she had been experiencing domestic violence, a packet of pills from her own medicine cabinet. But Anna’s husband was monitoring his wife’s communications. He called the police, who confiscated Anna’s pills and later searched Wydrzyńska’s home.

Wydrzyńska now faces up to three years in prison for helping Anna end her pregnancy and for the unauthorized possession of medication for abortion (which is on the World Health Organization’s list of essential medicines) with the intent to distribute it on the market. Her case, the first in which an activist has been prosecuted for providing abortion pills in Europe, will go to trial on April 8. Abortion activists and human-rights groups including Amnesty International are supporting Wydrzyńska through an online campaign, #IamJustyna.

Her case also offers a glimpse into what may be coming down the pike for those seeking and facilitating abortions in the U.S., where lawmakers are turning their focus to restricting and criminalizing the use of abortion pills. Their usage soared during the pandemic, fueled by the increased reliance on telemedicine and the lifting of the Food and Drug Administration’s requirement that abortion pills be administered to patients in person. State legislators reacted by introducing more than a hundred state-level legal restrictions on medication abortion in just the first quarter of 2022, including nine restrictions on the mailing of abortion pills, according to the Guttmacher Institute.

Wydrzyńska is part of the Abortion Dream Team (tagline: “Abortion is Awesome”), a group of four Polish activists who, since 2016, have counseled people on how to safely self-manage abortions. She and two of her colleagues, Natalia Broniarczyk and Kinga Jelińska, spoke to the Cut about their work in helping people when the medical system fails them. The #IamJustyna campaign is bigger than Wydrzyńska’s case alone: It’s about the “thousands of people self-managing their abortions around the globe, including the United States,” notes Jelińska. “What would you do if somebody’s calling you for help, desperately, and you are positioned and have the tools to help?” she continued. “Would you do like Justyna did?”

We met in Poland in 2019, when abortion access was already extremely limited, with about 1,000 abortions performed in public hospitals each year in a country of 38 million. Can you tell me what has happened to abortion access since then?

Kinga Jelińska: First, you have the pandemic, when home abortions and the model of self-managed abortion that we support have actually become very mainstream globally — not only recommended from a public-health perspective but even the most reasonable option under the circumstances.

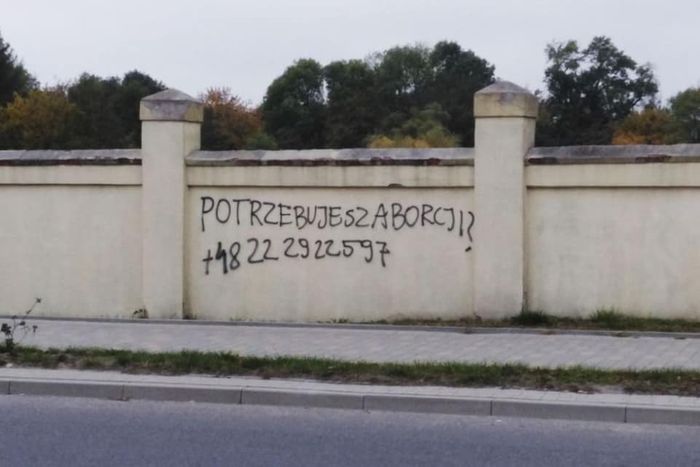

And then in Poland, there was the further restriction of the abortion law in 2020, so that people with fetal malformations were denied care in the public hospitals. Let’s keep in mind that we’re talking about a very small group of people. The vast majority of abortion is because people are pregnant and don’t want to be. However, this restriction provoked a major uproar and big protests. The protests were extremely supportive to another group we are part of, Abortion Without Borders. What we noticed is that despite the restriction to the law, paradoxically, many more people found out how to do an abortion safely and what their options are because of the public protests and the solidarity. The number of the hotline has been spray-painted everywhere now.

When I sat in on one of the workshops you gave instructing people on self-managed abortion, one of the people in attendance appeared to be surreptitiously recording your work. What sorts of interactions have you had with Polish authorities to date?

Justyna Wydrzyńska: At the training you attended, the police were informed about that, and the people who organized it had to go ito the police station.

Jelińska: There was a whole campaign where our faces were put on a billboard that was driven all around Warsaw and other cities with messages around abortion and killing — it was a very heavy response from the anti-abortion side. But we see it as a function of our success: They are only as annoyed at us as we are visible and unapologetic for our actions. Sometimes we get letters of inquiry requiring us to go to the police, but we see it more as harassment, keeping us anxious all the time. Like, now I have to go to the prosecutor again? It’s a very common strategy. It costs you time, it costs you resources, and it causes you stress.

Natalia Broniarczyk: To be honest, it’s not from the government, but very often it is from some activist from the anti-choice organizations who goes to the police with a sticker with our phone number or a photo of our activities. Then we have to go and explain why it’s not “helping” someone obtain an abortion. Sometimes police officers ask us, off the record, “Okay, so is this safe? This abortion with pills, is this safe?” And we say yes. And they say, “Okay, I will keep this number for my friends.”

Your colleague Karolina Więckiewicz, the fourth member of the Dream Team, is a lawyer. She told me she believes everything the Dream Team does is legal, and you have counseled thousands of people to date. Why is Justyna facing charges now? Is it because she went beyond counseling and guidance and materially helped by sending pills in the mail?

Jelińska: Counseling and providing informational resources fall under non-censorship laws and freedom of information because these are the recommendations of the WHO. So the campaign #IamJustyna is based on solidarity and on this peer-to-peer trend among women seeking abortion services because we are living in a state that is bankrupt, that doesn’t want to help you with abortion. While there is no official public data on the number of abortions performed in 2021, one newspaper asked the government about it and was informed there were 414. The doctors are also incredibly useless in this country. Even in cases where a woman’s life was in danger, they didn’t help in public hospitals. We cannot even trust that they will save our lives. There have been several cases of women dying because doctors won’t perform abortions. So we also want to call attention to this solidarity because essentially the whole of abortion care in Poland is reliant on people like Justyna.

Justyna, you had reason to believe Anna’s husband was very controlling — looking at her emails and text messages, going through her purse. Were you worried he would find out?

Wydrzyńska: I hear stories about abortion pills arriving from Women Help Women, an organization that sends pills by mail, and men will sometimes swallow them or put them into the toilet and flush it. I know those stories. I thought this might happen — that he would take the pills away from her rather than call the police. I really didn’t think it could happen.

After all the work you’ve done over so many years, now it’s come to this. Justyna, how are you feeling right now about everything that’s happened?

Wydrzyńska: I’m afraid this case will have a chilling effect on people who need information and support, because they’re afraid that calling us or writing to us could be dangerous for us and for them. So the campaign is to show that we will not stop working and we will not be afraid of these charges. And I’m not sorry for this.