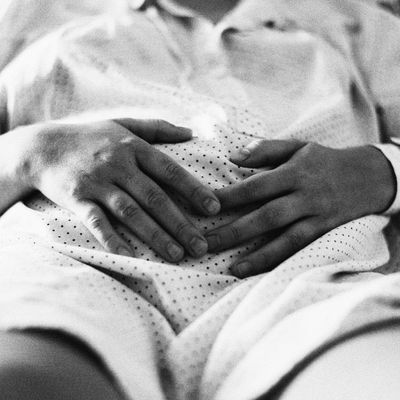

In the weeks since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, the impact on abortion access has been predictably devastating, with clinic staff scrambling to complete scheduled appointments in the face of impending closure and harrowing reports of patients being denied care even in the most extreme situations. But it’s also clear the decision’s damage extends far beyond patients seeking to end unwanted pregnancies. A woman in Texas, for example, says the state’s ban obligated her to carry her dead fetus for two weeks after her doctor declined to remove it surgically, citing the new law. Or there’s the doctor in Louisiana who says her hospital’s lawyer barred her from performing a dilation and evacuation after her patient’s water broke at 16 weeks, forcing the woman “to go through a painful, hours-long labor” to deliver a nonviable fetus vaginally. As the dust from the Dobbs ruling settles, doctors are increasingly finding themselves hamstrung by legal threats when it comes to treating patients in need of urgent care.

“OB/GYNs are apprehensive,” says Dr. Coy Flowers, a Lexington, Kentucky–based obstetrician and gynecologist who spoke in his capacity as vice-chair of the state’s American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists chapter. He’s hearing from doctors across Kentucky who “have a great deal of angst around seeing patients in clinical situations that fall in the gray zone for abortion care.”

For Flowers and his colleagues, the language of Kentucky’s law raises pressing questions around common pregnancy complications: Miscarriages, for example, are estimated to occur in 10 to 20 percent of known pregnancies and may require medication to complete. Ectopic pregnancies occur in about one of every 50 pregnancies, and though they will never become viable, they can become life threatening without treatment. These are just a few of the situations in which a doctor might have to make a timely judgment call to minimize potential harm, and while the Biden administration has clarified that doctors are legally required to provide life-saving care even when that means abortion, confusion lingers. Kentucky’s trigger law, which has been temporarily stayed, includes only vague exceptions to its near-total ban. If and when the policy goes back into effect, anyone who performs or “abets” an abortion may find themselves facing not only a fine but also the possibility of one to five years in prison. “The language in the law was crafted by individuals who have a political agenda,” Flowers says, “but don’t have any medical background or familiarity with the intricacies that surround required care for pregnant patients.” Across the country, OB/GYNs in conservative states are running into similar obstacles as maternal health care is thrown into legislative chaos. Flowers spoke with the Cut about about the unprecedented anxiety among his fellow doctors and patients.

Can you walk me through some of the most common and concerning pregnancy complications where care might be impacted by anti-abortion laws?

A lot of it will impact patients in the second trimester — patients who are, say, 20 weeks and have a placenta previa, who start to bleed uncontrollably and the fetus still has a heartbeat. What do you do? As a physician, if a patient is bleeding heavily, I would think we need to intervene and potentially deliver the nonviable fetus in order to save the mother’s life. However, now the law is left up to the individual prosecutors in each county to make the determination. Should we have transfused more blood? Should we have waited a little bit longer because, who knows, in an hour or two the bleeding may have stopped? Should a physician delay care until a patient is on the literal brink of death?

Often, we see patients at 16 to 20 weeks who have a preterm ruptured membrane. They break their bag of water. The cervix may or may not be partially open, but the fetus still has a heartbeat. That patient now is at grave risk of infection that can lead to sepsis in their bloodstream and be lethal. And we know these fetuses are not viable. So how long do we wait if there’s still a heartbeat? How gravely ill do we allow our patients to become before we intervene because the threat of monetary fine or being charged with a felony is a reality?

What does all of this mean for you and your office on a daily basis?

Physicians, and particularly OB/GYNs, we all got into this to do the right thing for patients, and we’re going to continue to do that no matter what. At two o’clock in the morning, faced with a situation where a patient has a rupturing ectopic pregnancy — or a bleeding previa or ruptured membranes and a fever and the possibility of infection — I can’t imagine that I would hesitate to do the right thing. But I can feel the anxiety and the uncertainty among my physician colleagues.

It’s also created pervasive anxiety among patients that I’ve never seen before. I have patients who are undergoing fertility treatments who are worrying about whether they should delay their fertility treatment until they’re certain about what kind of care they’ll receive if a complication should manifest itself. I have patients coming in every single day who are struggling with: Should they get their tubes tied? I have patients who are 22 years old calling and asking those questions. They’re saying, “I don’t know what’s going to happen in Kentucky if I get pregnant and it’s not the right time, or if there’s a complication and my doctor can’t take care of me optimally.”

I had a patient today who is currently pregnant and who was worried about the next pregnancy if there was a complication. She actually asked me, “How do you view this? Would you save the life of the mother or the life of the baby first?” Patients now think that physicians have to pick and choose who lives and who dies. And medicine is not that black and white. Everything’s about a balance and weighing risks and benefits to get the best outcome for that clinical situation.

What do you tell them? How do you answer a patient asking whether you would save her life or the life of the baby she’s hoping to have?

I sat down with her, and we spent some time talking about viability and gestational age and outcomes and how a physician approaches a clinical situation, trying to weigh the risk to the mom versus the benefits or risks to the fetus. I explained that we would do the best to figure out what exactly to do given her particular situation. It’s tough, but I tried to reassure her that, no matter what happens, we’ll do our very best to make sure she and her baby are well taken care of.

I’ve been reading reports about people experiencing difficulty accessing methotrexate, which could be used in an abortion but is typically used to treat certain cancers, arthritis, and ectopic pregnancies. Have you had issues with prescriptions that are unrelated to abortion?

Throughout my entire career, there have been staff at infusion centers for cancer treatment who have intermittently reached out about a methotrexate prescription to say, “Hey, I really need to know exactly what it is you’re using this for because I want to make sure I don’t interrupt a viable pregnancy.” And you have to go down that road and try to educate them. Within an hour of Roe being overturned, I prescribed Cytotec, one of two drugs commonly involved in medication abortion, for a patient who was having a miscarriage without a heartbeat to help her complete it without having to undergo a D&C. Fifteen minutes later, the local pharmacy called my office wanting clinical information about why I was prescribing it.

Now the pharmacies call every single time we prescribe Cytotec for a miscarriage to make certain that this is not for an elective termination. I don’t think pharmacists really want to be in the business of policing their physician colleagues, but Kentucky’s trigger law says that any particular person who assists or aids in the procurement of a pregnancy termination could be liable for monetary bond or up to five years in jail for a class-D felony. It could be a patient’s best friend who drives her to the pharmacy or drove her to the appointment to see the physician. It could be the pharmacy tech who’s just filling the medication. It could be the check-in person for the office. We don’t know how wide a net the prosecutor in any particular county would try to cast.

It sounds like a lot of time and effort to try to untangle all of this red tape and uncertainty.

As if our world wasn’t stressful enough right now. We’ve got the pandemic, our institutions are failing, and then, for these women, the added uncertainty about the health of their own bodies should they choose to get pregnant or should they choose not to. You have a patient whose birth control failed, and now a government official is trying to be part of the team that cares for her. It’s frightening. Then there have been reports, and actually warnings in the Dobbs decision, that contraception may be next on the chopping block. My patients are worried about that. I also have lots of LGBTQ patients who are worried about losing the right to same-sex marriage and other issues concerning their communities. The anxiety and feeling of not having control over their health has really been palpable with patients. It also transfers over to my staff, who work their hearts out to make sure that these patients are being well cared for.

We know the pro-life movement wants to limit the number of first-trimester or elective terminations. By doing that, they’re also sweeping up this whole significant group of people who have really desired pregnancies. They have hopes and dreams that surround those pregnancies. And then something goes wrong, and everyone is in tears. It’s gut-wrenching — it’s not anything close to what that patient ever thought would happen. The language now in these trigger laws puts that particular group of patients into a situation where their lives and their health can be in jeopardy. My heart goes out to them.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.